This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 4, "The Chinese: 100 Years in the South." Find more from that issue here.

One developer had planned tall — so tall that even if he cut 70 feet off his condominium, Miami's building rules would have left him a wafer of a building: 23 stories tall, two feet wide. Another developer wanted a 20-story hotel where the zoning laws allowed for one only half that size. A third developer claimed he'd made a mistake in his plans. His condo was turning out to be 20 percent bigger than he had originally said it would be. Cut it back, said city planners.

The developers turned to the Miami City Commission, and it bailed all of them out.

Ten extra floors here, three there. Shaving away parking requirements. Squeezing off required open space. As new buildings climb up, Miami's zoning laws tumble down. What's left is a patchwork of exceptions, always open to a developer's new request. "I can't see too much difference between having what [planning] we have here and having nothing at all," laments architect Alfred Browning Parker. Parker designed the city-owned Miamarina, a people-oriented complex of docks and shops on Biscayne Bay. He is sensitive to the idea of a city on the bay, open to views of sky and water. Says Parker of that vision, "The opportunity is not blown, but it's certainly wasting."

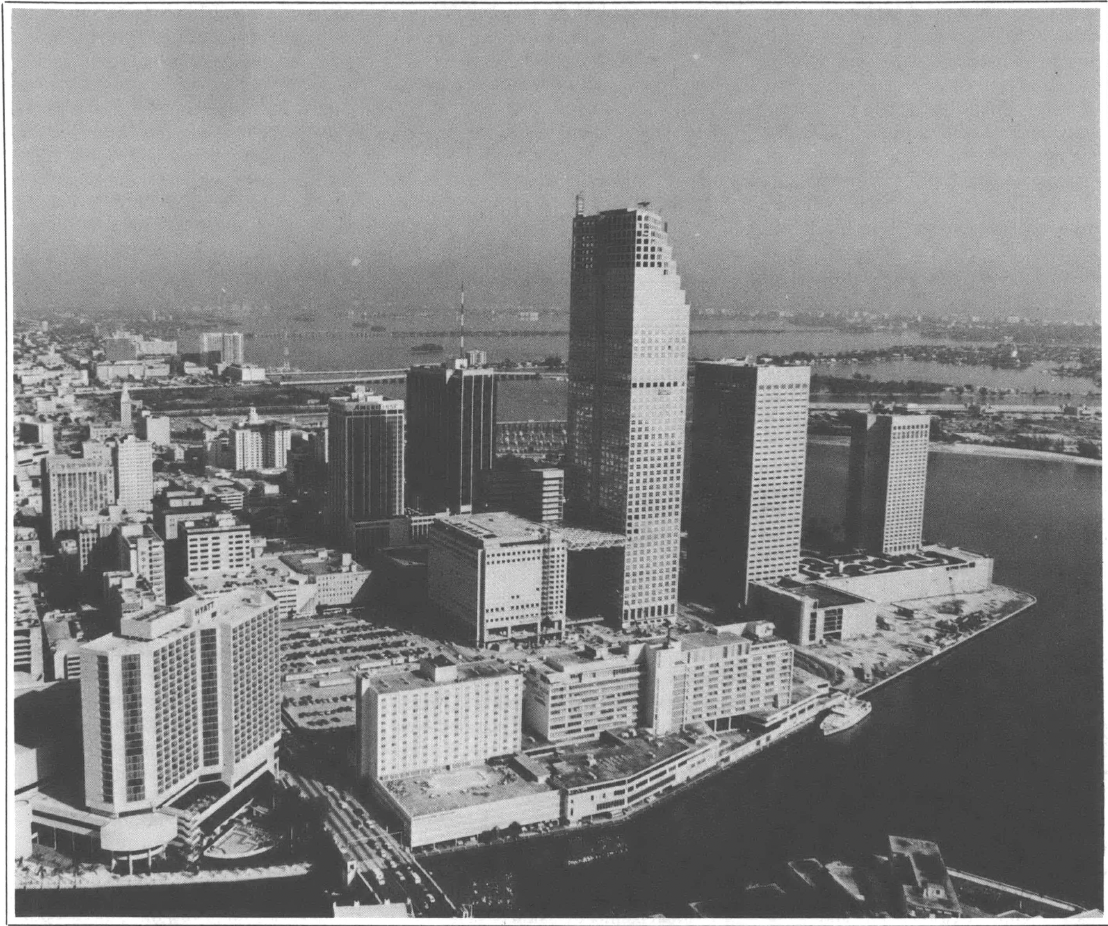

While the national press portrays a Miami with a taste for cocaine and international intrigue, the city's true love affair is with concrete. During one of its periodic building booms, one might mistake it for one of those Saudi Arabian cities conceived, designed, and built in less than a decade. Cement trucks clog the streets; cranes perch atop every other building. And the news is clogged with stories of starts and completions, cornerstones and top-offs.

The love affair has its costs in human terms, as those who can afford $200,000 for a two-bedroom condo or similar astronomical rental fees for office space are increasingly the only people with access to a reasonable quality of life in the city.

Only a grassroots initiative in a community with a two-mile stretch of open coastline prevented a complete wall of high-rises from closing it off. A few amenities like view corridors to the water and a 50-foot building setback from the shore are now required.

Coconut Grove, Miami's most walkable neighborhood, with its small shops, restaurants, parks, and sidewalk cafes, faces an onslaught of mid-rise hotels, banks, and apartments.

A pending explosion of apartment and condominium development along the Miami River threatens to price fishing boats and tramp steamers right out of the city.

To assess the impact of Miami's wide-open development on the city and its politicians, and to see whether the regulators of the building industry are doing their jobs, we undertook a three-month investigation of the city's planning and zoning system in 1983. We found a system that has broken down, that is self-defeating at best, corrupt at worst:

• The Zoning Board and City Commission ignore their own laws and procedures in granting variances from zoning restrictions.

• The land development industry is the largest single source of campaign money for incumbent city commissioners.

• Some city zoning inspectors have helped petty violators cheat the system.

• Poor zoning enforcement has contributed to the creation of slums in northeast Miami and Little Havana and to Manhattan-like congestion in high-rent neighborhoods.

Florida law requires cities to plan for future growth, using zoning as a tool to enforce land-use plans, but the way a city applies its zoning laws is largely its own business. Regarding our finding that the record shows an established pattern of zoning law abuse in Miami, Mayor Maurice Ferre told us, "I think your conclusion is basically correct." Mayor Ferre also, however, sees nothing wrong with the haphazard system of planning and zoning. Describing the force behind it, he says, "What determines things in a free society is the marketplace."

The scene of the marketplace is the City Commission, which devotes every other meeting to planning and zoning and spends enormous amounts of time listening to technical presentations. New building densities — the figures that determine how much marketable space a developer will have — are set like prices at a beef auction; developers lobby for more and city planners ask for less. When it is time to act, the commission follows a simple credo: more is better.

Critical zoning decisions that affect the quality of city life are made with scant evaluation of their impact on such basics as traffic congestion or sewer capacity. Brickell Avenue, which follows the shoreline just south of downtown, is a prime example. In 20 years it has changed from a tree-lined avenue of upscale mansions to a congested strip of luxury high-rise condominiums and office buildings housing much of the international banking and commercial enterprises that have turned Miami into the financial capital of Latin America. The city's master plan for the area, the guiding document required by state law, is a one-sheet statement of general principles littered with inconsistencies and errors, and its principles have been lost in a maze of variances.

Besides the high-rises already in place on Brickell Avenue, another 2.6 million square feet of development are in final design stages, with more on the way. There is a new proposal to hike density on the street by another 70 percent. City planners say traffic congestion there could soon have a choke-hold on the area, but they have never done a full-scale traffic study and don't know how to cope with Brickell traffic or how much it will cost or who will pay. When traffic problems beset the area's Dupont Plaza high-rise complex, the state, county, and city put together a $34.7 million package to finance a new highway link to Interstate 95.

That illustrates one way to get things done, in Mayor Ferre's opinion: "As mayor of Miami, it's my opinion that there are two ways that major roads get built. One's through political influence. The other way roads get built is where the demand requires it — there's a crisis." What about planning? Says Ferre, "I think all it is is a certain restraint. It slows things down."

Others, however, point out the social costs of this laissez-faire attitude. Architect Robert Bradford Browne, an adviser to the city's planning department, says, "What you do is you shift the responsibility for making a city work to after it's been overcrowded and overbuilt. A guy buys something that can hold 200 units by the [zoning] law. He changes the law to get 300 units and makes that much more money. The little guy gets saddled with the big guy's ability to squeeze the system for profits. You put very expensive solutions down the road onto the taxpayers."

In Miami, the most common way to get 300 units where the law allows 200 is to go for a zoning variance, an exception to the rules that can be granted by the Zoning Board or the City Commission. Variances are intended to take care of unusual circumstances — safety valves to prevent injustice. Generally, they are supposed to be granted only when something unusual about the size, shape, location, or natural features of a piece of land create a hardship for the owner. The hardship, according to theory, may not be caused by an action of the owner. Court decisions have established the criteria, and the city has adopted them in its zoning ordinance.

The textbook example of a hardship is when a lot's unusual shape — triangular, for example — makes it impossible to build a home on it without violating setback rules. Variances also are supposed to be the minimum revision of the rules needed to allow "reasonable use" of the property. According to zoning experts, Miami — a relatively new city on flat land, where property was divided in a grid pattern — has little property with true hardships. And the city's professional planners oppose variance requests in most cases, saying they don't meet legal requirements.

But the Zoning Board and City Commission usually don't listen. When we examined variance requests in city files, we found innumerable questionable claims of hardship. For example, a duplex owner who wanted to build an addition said, "Granting this will solve a big problem between our children." A property owner who wanted to build a porch said, "This should improve the value of the property." A homeowner asking for an addition said, "House too small." All these requests were granted.

In fact, in 1982 the Zoning Board granted variances in 91 percent of the cases where the city planning staff recommended denial, and the City Commission approved outright rezonings in nine out of 10 cases where planners disapproved. Why do board members and commissioners so consistently ignore the advice of the people they hire to advise them? Our examination of the campaign finance records of city politicians, which shows the land development industry to be the single largest source of campaign money for incumbents, suggests at least part of the answer.

In 1963 the late Robert King High was mayor and Maurice Ferre, then 28, had just become president of his father's cement company. Miami's skyline was a scattered collection of squat buildings, and bayside mansions still lined Brickell Avenue. Martin Fine, an up-and-coming real estate lawyer, stood before the City Commission to argue in favor of a zoning variance for a 13-story apartment house he wanted to build near the Miami River. Mayor High disqualified himself from voting because Fine had given him a $25 campaign contribution. High's abstention, which was not required by law, made headlines. Today, political sensitivities like High's have gone the way of $25 campaign contributions and nickel beer.

Our study of finance records, done for the Miami Herald, analyzed contribution reports from recent municipal elections, attempting to identify the source of every contribution of $100 or more. We found that the fundraising role of zoning lawyers, developers, real estate brokers, contractors, and other professionals in the building industry has expanded with the increased cost and complexity of running for office in Miami.

The land development industry gave $159,100 to Ferre in 1981 — 45 percent of his campaign chest, up from 36 percent ($65,125) in 1979. Most of the industry's money goes to incumbents. For example. Commissioners Miller Dawkins and Demetrio Perez, Jr., received only a small share of their campaign money from this source when first elected in 1981: 25 percent and 12 percent, respectively. And Commissioner Joe Carollo received 23 percent from the industry when first elected in 1979. But when Carollo sought a second four-year term in 1983, that share rose to 44 percent. Incumbent Commissioner J.L. Plummer was reelected in 1979 with industry support accounting for 26 percent of his funds; the figure jumped to 45 percent in 1983.

The politicians generally discount the significance of this support. Says Plummer, "I never look at my contribution list in making decisions." And Carollo shifts the subject with his comment, "I'm not as concerned about developers contributing to my campaign as about some other elements of this community. Communists and drug pushers — they're trying to become active in the city of Miami."

The fact remains, however, that the developers, architects, and real estate lawyers who contribute to city candidates at election time appear before the City Commission at one time or another to ask for zoning variances or rezonings, and the financial dividends of favorable rulings are sizable. Comments on what it all means vary widely. As is typical of studies of connections between campaign finances and political influence, direct causal links between particular contributions and particular commission decisions cannot be alleged. Most participants in the game try to downplay its importance, often sounding disingenuous or naive in the process.

Former city attorney George Knox describes the relationship as a "legitimate" form of patronage. He told us, "There is only one major opportunity to exercise patronage under our [commissioner-manager] form of government, and that is zoning." Later Knox revised his statement to: "I believe that these people [commissioners] do what they think is best for the development of the city, and if as an ancillary benefit they get contributions, that's fine."

Martin Fine, who doubles as attorney for private developers and finance chairman for Ferre — the mayor credits him with raising at least $25,000 in 1981 — denies any link between campaign dollars and zoning decisions. "I think that these decisions are not made on the basis of patronage. They are made in part on the recommendations of professional staff, on the factors in each individual case, and the developer's past track record."

Fine is a frequent petitioner before the commission. Besides his private law practice, he is a board member of the city's Downtown Development Authority and chair of the Downtown Action Committee of the Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce. Besides his fundraising for the mayor, he is a $1,000 contributor to Commissioners Plummer and Carollo. Whether seeking an increase in density for a client in the burgeoning uptown area or rewriting a zoning law to protect a Brickell Avenue client, Fine is seldom turned down, even if city planners disagree with him. As one long-time city planner told us, "You feel you're at a disadvantage when you face Mr. Fine at a public hearing." Then he added, "Don't quote me. I like my job."

Mayor Ferre, for his part, insists that Fine keeps his political and business interests apart. "Marty Fine is a very poor example of what you're trying to research," Ferre told us. "There are others who are better. There are others who are bolder about saying, 'I want this and I want that.' Some of them get pretty rough."

Ferre says it would be "hypocritical" to say that campaign contributors don't expect something in return. "People who give money in government . . . usually have the expectation of being heard — access." But, he said, "I totally deny and I totally reject the premise that it categorically, by implication, explicitly or implicitly, goes beyond that. I don't deny that there are developers around here who are important people in the structure of government and they make contributions. But honest to God, I don't think I would have voted any different if they had or hadn't."

Industry insiders had various things to say when asked about the money/zoning link:

• Al Cardenas, a fundraiser for the mayor, a local partner in the company that holds Miami's cable television franchise, and a well-known political activist: "Whether my public involvement lends credibility or not to my arguments, I don't know. That has to be answered by the people who hear them."

• Earl Worsham, a real estate developer: "Unfortunately, it's kind of a necessary evil. Candidates have to spend a bunch of money, and the only place they can get that money is from people that can afford it.

• Tibor Hollo, who convinced the commission to grant downtown zoning intensity to his uptown apartment development and who got zoning variances for two other uptown projects, claims not to know the effect of his campaign contributions: "That's a damn good question. I'd love to answer it. I don't know. I don't want to speculate. When I make a contribution, it is done from my heart and I couldn't care what happens to me."

• David Weaver, a Canadian developer who built Brickell Avenue's Barnett Bank Centre: "The people who are in real estate are sooner or later going to be forced to go before the City Commission. That leads to a whole question of motivation. One level is just purely that when you stand up in front of the commission you would like to see some friendly feces. "But he also says he supports politicians whose philosophy and actions in general create a good climate for business. "You're not buying the right to a guy's mind." Nevertheless, he describes campaign contributions as a "form of investment" for anyone in the land business in Miami.

• Robert Traurig, an attorney whose list of clients reads like a roster of Brickell Avenue developers and a politico who raised $10,000 for Mayor Ferre in 1981, says being a political contributor "is not concomitant" to having a successful zoning practice in Miami; making contributions is "a normal thing to do" when "a relationship develops as a result of ongoing contact" with an elected official. "The fact that I make contributions has no relationship generally to the matters I present. My contributions have never been related to land-use issues."

• Steve Ross, a political deal-maker and unofficial historian of Miami's backroom politics: "In the federal government and in the state government, there are hundreds of different issues and interest groups involved. . . . The city of Miami is restricted to five areas: police, fire, sanitation, parks and recreation, and zoning. Only one of those leads to a source of political contributions; the others don't. It's where the action is, in the building industry basically." Ross, who sometimes lobbies for developers with zoning problems, also acknowledges readily that land industry contributions are a means of gaining an "edge." He says, "People in business don't have the vote strength of newspaper endorsements or a homeowners federation. Contributions are how they support those they agree with."

Brickell Avenue development, on close inspection, yields a revealing picture of how the system works when big money is involved. The city touts the neighborhood envisioned by its plan as a cosmopolitan, urban one where city dwellers on their way to work will stroll by plazas, shops, cafes — even sidewalk Shakespeare — amid the corporate headquarters, international banks, and luxury condos. But the vision is threatened by developers overrunning the building limits.

"There really is no [zoning] ordinance for Brickell," says Zoning Board administrator Aurelio Perez-Lugones. "Every time someone comes in for a variance it's granted." After-the-fact planning and a pending avalanche of new construction now threaten the green, open setting that drew people there from Miami's paved-over downtown.

Variances are almost routinely granted to accommodate buildings larger than the zoning ordinance allows. Then the city relaxes zoning rules to allow higher density. And then more variances are granted, as the cycle begins again. Brickell Avenue has become "Variance Valley," where market forces, rather than a city plan, dictate growth.

The boom began in 1960 with approval of a development at the southernmost end of the avenue near the Rickenbacker Causeway, which connects the mainland with Key Biscayne. KWG Associates received variances for two 21-story apartment buildings on land zoned for single-family homes. The design changed — a single Y-shaped apartment, the Town House that exists today, was eventually built — but the high-rise pattern was set.

Next came developer James Albert with a plan for an upper Brickell site where the Four Ambassadors hotel and condo complex now stands. After an initial rebuff, Albert won approval of eight variances. A futile, but prescient, protest was raised by then-planning director Dudley Hinds: "Conceivably, in a few more years we could have these things lining the bay front between . . . the Miami River and the Rickenbacker Causeway. It would be proper to consider the implications throughout the area."

The Four Ambassadors project as finally built on the site required 11 variances in 1965, including one to increase floor area by 80 percent over what the law permitted. "If we create a variance for this site," warned Hinds, "there is no reason whatsoever for refusing similar applications . . . all up and down [the bay]."

Today, after scores of variances and several rewritings of the zoning laws, Brickell developers make the early builders look like pikers.

A cluster of condominiums midway along the avenue represents the latest in residential developments in the area — prime examples of oversized buildings, in the opinion of some planners. Some residents of the Villa Regina, for instance, will have a close, unobstructed view of a red wall 30 stories tall. The wall forms the north side of its neighbor, The Imperial.

The Imperial, a slab-like building, sits on a long, rectangular lot perpendicular to Biscayne Bay. It is so tall that required setbacks on the relatively narrow lot left no room for the building. It was made possible by variances that knocked some 50 feet off each setback requirement.

When variances granted The Imperial, the Villa Regina, and the still unbuilt Santa Maria were challenged in court in 1982, a circuit court judge struck down the city's planned area development ordinance. With another suit pending against The Imperial, the City Commission accommodated the threatened developments by approving a tailor-made revision of the zoning laws for the entire lower Brickell area. Drafts of the new law were prepared by the firms of lawyers Martin Fine (representing The Imperial), Murray Dubbin (Villa Regina), and Robert Traurig (Santa Maria).

Upper Brickell's commercial area is the stage for the next round of zoning changes and bigger buildings. Planners fear the additional rush-hour traffic created by new office buildings will push the road system beyond its limits. The basic problem is that there aren't many ways to get in and out of Brickell. Biscayne Bay lies to the east. The aging Brickell Avenue Bridge is the only link north to congested downtown Miami. Interstate 95 blocks access to the west. Crowded South Dixie Highway and the Rickenbacker Causeway converge at Brickell's southern tip. Routes to 1-95 — the most promising relief valve — are limited to two east-west streets, but existing buildings hamper expansion of the road system.

City planner Jack Luft says, "We lost sight of what makes sense on Brickell. How much is too much? How far is too far? How little is too little?" But Mayor Ferre says the traffic crunch, already acute at some intersections during rush hour, poses no obstacle to development. "Don't worry," he says. "When all these people put up those buildings, we will find solutions collectively. Oh yes, it's going to cost $40 million, or $10 million, or whatever. But I want to tell you I would rather have the growth pattern that I think is necessary."

Ferre, who envisions Miami rivaling New York, Boston, and Houston in downtown density as well as importance, believes anything short of skyscrapers in Brickell is a luxury the city can't afford. In defense of his build-now-plan-later philosophy, Ferre says heavy congestion like that which choked Dupont Plaza is acceptable. "If we had done nothing [about traffic at Dupont Plaza] it wouldn't be as bad as New York City, and New York City survives pretty well."

The latest higher-density proposal to amend zoning laws, which Ferre has endorsed, would benefit two major developments, the 1.2 million square-foot Nasher Plaza and the 1.1 million square-foot Tishman-Speyer project. The attorney for both developments and the author of the amendment are one and the same: lawyer Traurig.

They are only part of what's expected to happen soon. The city believes at least eight projects with a combined floor area totaling nearly five million square feet will soon be built in the upper, or north, Brickell area — more than doubling what exists now. They will be taller and larger than anything now in the area, and demonstrate once more why we dubbed the neighborhood Variance Valley.

Miami's high-rent districts hold no monopoly on lax enforcement of zoning laws, unfortunately, and the City Commission has thereby allowed several healthy neighborhoods to degenerate into slums. For the once thriving neighborhood of East Buena Vista on the city's northeast side, the long slide began nine years ago when the owners of a house there illegally divided it into several apartments. Neighbors say they complained to city zoning inspectors, and a now-familiar cycle of complaints and inaction was bom.

Fifty years ago, the area was home to Miami's elite, as they built two-story Mediterranean villas with sweeping arches and Spanish-tile trim. In the 1960s the area evolved into a middle-class, integrated neighborhood. Then the mid-1970s trickle of Haitian refugees into Miami turned into 1980's flood of boat people. With it came illegal rooming houses, absentee landlords, and overcrowding, much of it in East Buena Vista.

Today, rotting mattresses and rusted, abandoned refrigerators vie with other rubbish for space along the shady streets. A home on one comer doubles as a takeout restaurant where cars double-park at dinnertime. Rundown homes are everywhere.

"We consider poor enforcement of zoning laws the primary cause of the deterioration," says Richard Rosichan, who moved into his home there 13 years ago. "It's easy to get mad at the Haitian refugees and the absentee landlords. But the city has been reluctant to take action from day one."

East Buena Vista is only one of many Miami neighborhoods that have stood in the flow of immigrants and refugees. The city official responsible for zoning inspections agrees that poor enforcement has contributed to their decline. Miami deputy fire chief David H. Teems, who took control of the city's building department in 1982 when it merged with the fire department, says, "Zoning enforcement was nil. It was totally ineffectual as far as I was concerned. There was no way to tell if the laws were being met. Without good zoning enforcement . . . you allow the neighborhood to deteriorate. You start the cycle that allows a slum to occur. What happens in the neighborhoods is the crime of it all."

Miami's poor black neighborhoods, Liberty City and Overtown, have felt the effects of lax zoning enforcement as well. Wellington Rolle, a black who served two terms on the city's Zoning Board, believes the carte blanche that's been given builders has hit black areas particularly hard, producing a hodge-podge of building types that reduced property values and sped up deterioration. "If you go through the records, you'll find in the black areas that people got variances expressly to make a higher profit," he says. "It's been obscene in the black community. There's been so much overbuilding that in places there's no room for air, ventilation, or light. And children are living in there."

Although there are recent signs that zoning code enforcement in inner-city neighborhoods has improved, few are optimistic that Miami's attitude of neglect toward planning and zoning will change. Our examination showed that, until recently, the city's zoning enforcement was hampered by what Teems describes as systematic corruption, political interference, and poor management. "It was a den of thieves," says Mayor Maurice Ferre. We found:

• The damage from poor enforcement may already be irreversible in some areas. In addition to East Buena Vista, Little Havana merchants and property owners blame the city for a growing slum in eastern Little Havana now known as "Vietnam" because of its resemblance to a war zone. "Enforcement fell off and a large influx of refugees and other factors started to move that area toward a slum," says Teems. "We're trying to turn that around."

• In the past year investigations into the city's building and zoning inspection force found evidence of corruption. Five city inspectors resigned, retired, or were fired during zoning-related investigations. Officials believe that inspectors hired to enforce zoning laws actually aided zoning violators in circumventing the law and provided such services as drawing bogus plans — work clearly in conflict with their city jobs, officials say.

• Disappearing files, doctored plans, and altered building permits were a way of life in the inspections department. To some extent, those problems still occur. When one building inspector was fired in late 1982, his lawyer obtained a series of intracity memos from police and other officials describing the firing as unjustified. They were forgeries.

• Developers and contractors routinely gave gifts to city employees, a practice that continues. Some developers regularly visit the building department around Christmas time, handing out bottles of liquor to employees. Whenever superiors challenge the practice, such gifts are simply sent to employees' homes, according to former employees.

• Those who have violated Miami's poorly enforced zoning rules range from slum landlords to Thomas Gallagher, the minority leader of Florida's House of Representatives. Some friends and supporters of top city officials have successfully ignored or delayed enforcement efforts. One is restaurateur Felipe Vails, a supporter of Mayor Ferre. For five years, Vails was repeatedly cited for improperly converting a house into the headquarters of his small business empire. Vails was never fined for the alleged violations, and the city never halted what it considers the illegal use of his office. Says one inspector who cited Vails, "He thinks he has an 'in' in the mayor's office. He's one of those guys who thinks he's got political pull."

• Until recently, the city had no way to determine whether zoning inspectors actually check on the more than 2,000 complaints they receive annually. The city also failed to monitor rechecks to see whether violators were complying with zoning rules. In fact, inspectors rechecked only one-fourth of the violators in the 1981-82 fiscal year. When the city tightened supervision of inspectors in 1982, such rechecks quadrupled. Top inspection officials cite examples of inspectors tearing up complaints without checking them and issuing citations without turning in copies to the city's master file.

• Only in 1982 did the inspection division of the building department start keeping a centralized file. Before that, plumbing, electrical, zoning, and structural inspectors could each cite the same property without knowing about the other citations.

• During the 1982-83 fiscal year, the equivalent of just three city employees performed all the field inspections in Miami. In 1983 the number of field inspectors was increased to seven, and neighborhood zoning sweeps were instituted under the fire department's control. But inspectors still aren't required to report all zoning violations, just the ones for which they receive complaints.

• When violators face fines or court action, they often win variances from the Zoning Board and City Commission. The ease with which such variances are obtained further undermines enforcement efforts.

The case of Felipe Vails, who gave Mayor Ferre free use of his Versailles restaurant for a $500-per-person campaign breakfast in 1981, epitomizes the city's shoddy zoning enforcement. The case involves a house just off Calle Ocho, the main street of Little Havana, located on a lot zoned for residential use near the Versailles.

City officials contend that several years ago Vails illegally paved the lot, which is now used for extra restaurant parking. The city also says Vails converted the house into his business office without permits and in violation of zoning rules. The city notified Vails of a violation once in 1974, wrote letters threatening court action in 1978, notified him of violations again in 1981, and sent Vails a new round of zoning and building code violation notices in 1982. After that, Vails applied to have the City Commission rezone the property for commercial use.

The enforcement efforts never interrupted his business operations. A sign, called illegal by the city, still directs restaurant patrons to the allegedly illegal parking lot.

Vails denies using political pull: "I never called Mayor Ferre or any commissioners for any of my zoning problems." Says Ferre, "I don't know anything about it. I may have seen Felipe Vails twice since the [1981] election."

"It was like everything else going on around here," says Teems of the Vails case. "Either somebody keeps [the case] out of the system or the particular inspector involved was not interested in doing anything. Things would get into a niche and not go anywhere. God knows what other cases like this will pop out."

What does the future hold? Urban designers worry about the high price Miami will pay if it continues to grow without a plan. The bayfront and riverfront will disappear behind a curtain of concrete, "people places" like Coconut Grove will be threatened, and increased traffic will choke overbuilt areas.

The waterfront faces the greatest development pressure in the next five to 10 years. "Views of the bay and the river — those are the resources that are limited," says Miami planning director Sergio Rodriguez. There are several areas of concern:

• The Edgewater neighborhood, a prime area for new high-rise development, a few blocks wide between Biscayne Boulevard and the bay, running north for a couple of miles from just uptown to the crosstown expressway connecting the international airport with Miami Beach. One of Miami's older neighborhoods, Edgewater now contains medium-sized apartment houses and single-family homes. A new zoning ordinance will permit medium to high-rise apartment complexes. And, because parcels of land are relatively small, planners fear that overbuilding will squeeze out open space. "You could end up with a lot of walls, parking garages, security gates," says city planner Jack Luft.

• The Miami River, a home for tramp steamers and fishing boats just three blocks from downtown. Planners consider the river a virtually untapped resource with vast development potential. They want the present industrial users of the river to co-exist with restaurants and residential development. Says planning director Rodriguez, "It's a working river, that's part of its character. We don't want to take out the industrial uses." But if apartment houses and condos are allowed to take over the river, the steamboats and fishers will head north to Port Everglades, near Fort Lauderdale. "There's no place else for them to go," says Luft.

• Coconut Grove, where high-rises are already marching up South Bayshore Drive. Though Luft predicts that the Grove's waterfront won't develop much more, he says the North Grove and the business district will change: "The downtown area will be much more intensified. The scale [of buildings] will change from one- and one-and-a-half-story profiles to three to five stories." One long-time Grove activist feels the once-neighborly urban village is being slowly consumed. "There's a tension between what the old Grove was and what it's going to be," says Joanne Holzhauser. "The Grove is a living thing. You reach a point at which damage cannot be reversed."

If the city's record of giving in to developers' demands doesn't change, some observers see a bleak future. According to Nicholas Patricios, director of the urban and regional planning program at the University of Miami, "We're losing all these unique places and we don't seem to have the ability to create them anew. When we try to create new urban places, we don't seem able to make them as attractive as the ones we replace."

The loss of water vistas and quaint neighborhoods troubles planners, but the traffic generated by new development is a more pressing problem, and one the city alone can't handle. Barry Peterson, director of the South Florida Regional Planning Council, says the future will pit city demands for new roads against the highway needs of neighboring counties and the state as a whole: "I don't think the state and federal governments have an obligation to rebuild [roads] just because local government allows so much development that it overwhelms the existing facilities. It's not reasonable to expect people in other parts of the state to send their tax money here to solve problems we created locally."

At some point, Peterson feels, Miamians will face a simple question: can they get from one place to another in the new Miami?

Former assistant city manager Jim Reid acknowledges that traffic and transportation problems must be solved if the new Miami is to be economically viable. "Access," he says, "is marketability." Though the traffic problem won't be easy to solve, Reid says that Metrorail and additional people-mover loops to serve the Brickell Avenue and uptown areas will ease the crunch on the streets. He said the additional people-mover loops carry a $200 million price tag. But Peterson says Metrorail alone won't solve the traffic problem, and Patricios adds, "There's a lot of new development that doesn't seem related to any mass transit system."

Once again, Mayor Ferre's preferred solution is to allow the market a free hand and deal with crises after they've occurred. But Peterson says that's inviting chaos: "The market doesn't understand all the consequences of the players' actions. That's why we have overbuilding and boom and bust in office and condo development. The market isn't all-knowing and it's very bad at predicting side effects." The market can also turn against a city, Peterson adds: "If there's too much [traffic] friction, people will make the choice to relocate somewhere else."

Many say the key failure of Miami's haphazard planning is inadequate preservation of the city's most valuable resources — easy access to the bay and river, subtropical greenery, and an outdoor lifestyle. "We need to better balance the public's needs with the interests of private developers," says Patricios.

Reid sees a similar need: "The nature of the system is that people want to get more out of it. At every point you try to respond to [developers'] requests by trying to get something extra for the public." But, while the city staff argues for zoning that guarantees setbacks, open space, plazas, and other people-oriented amenities, the City Commission usually sides with developers.

For change to take place, in the opinion of architect and occasional city adviser Robert Bradford Browne, planning and zoning must become politically important issues to average Miamians. "Philosophically, the town and its leaders have to embrace the idea that zoning is important to a better living environment. You have to make [voters] aware that they need some kind of control in zoning so they elect people who have [a pro-planning] philosophy. Without the active desire on the part of the political masters of this town, you're not going to change. Zoning should not be the political power base of politicians. It should be something that assures the quality of life."

The main politically active force in Miami planning and zoning is the land development industry, the adversary of the planners. And, according to political power broker Steve Ross, the reason the commission can carry out its planning-by-variance zoning is that the city's large Hispanic and black voting blocs don't care. He says debates over buildings on Brickell Avenue are remote issues for a shopkeeper in Little Havana or the mother of an unemployed teenager in Liberty City. "I never met a black or Latin environmentalist," says Ross. "The environmentalists are upper-class Wasps or Jews who say: 'I've got mine, I don't want any more people.'"

Politically active architect Willy Bermello agrees that zoning is a low priority with Miami voters, but resents Ross's linking that to blacks and Hispanics. "That would apply to any large metropolitan area in the United States," says Bermello. "Zoning isn't a high priority issue, whether the voters are black, Latin, or Anglo. Generally the masses aren't interested. They view zoning as something for from them and the perception is that no matter what happens, deals are being cut."

Wellington Rolle agrees that black voters in Miami generally understand little about zoning: "The black community is able to discern the bottom line, but it isn't able to discern that zoning eventually has an effect on the character of the community. It is a lack of education. More interest on the part of the black community must go toward that process."

As Alfred Browning Parker, the visionary architect who designed Miamarina, says, poor planning hurts everybody: "A society is going to get pretty well what the society demands. If society is going to opt for crowded streets, impossible traffic, for making a buck as fast as you can and building as high as you want, that's what it's going to get. And we're certainly getting it."

Tags

Bob Lowe

Bob Lowe and R.A. Zaldivar are reporters for the Miami Herald. This article is excerpted from a five-part series in that newspaper. (1984)

R.A. Zaldivar

Bob Lowe and R.A. Zaldivar are reporters for the Miami Herald. This article is excerpted from a five-part series in that newspaper. (1984)