This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 4, "The Chinese: 100 Years in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Music pumps from a radio on the counter top as Chuck Davis tends a pot of cheese-grits bubbling on the stove. Davis is director of the nationally known, New York-based Chuck Davis Dance Company, one of the leading African-American dance troupes in the U.S. He also serves as a consultant for the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, and organizes the annual DanceAfrica Festival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

A big man — six feet, five and a half inches and 230 pounds — Davis wears a blue ankle-length wrappa gathered around his waist African-style and a tie-dyed T-shirt. His presence fills the entire room. Long arms looped with silver bracelets snake out from his body and jab the air as he makes a point. His rich baritone explodes in a whoop of laughter or just as suddenly drops to a compelling near-whisper. The smell of fishcakes seeps from the oven, and Davis, putting home-baked bread on to toast, breaks out into a snatch of finger-snapping and hip swings, dancing to the backbeat of a funky jazz number on the radio.

What's this man doing dancing around in a kitchen in North Carolina?

In September 1983, Davis moved back to his native South from New York to start his second dance company, the African-American Dance Ensemble. Twenty years in New York is no short stint, and the decision to move was a big one. Davis describes the moment in almost mystical terms: "My move to be here was meant to be," he says. As he sat on the shore of the Atlantic in Senegal the previous May, he recounts, gulls swooped overhead and sand crabs skittered along their frenetic paths. Further down the beach his company was rehearsing, and from time to time the faint sound of a drum call would reach him over the breaking of the waves.

Davis sat, uncharacteristically immobile, sketching figures in the sand. "My spiritual forces, my African and American ancestors, were all around me at that point. I just decided, well, if there is anything you want to do, tis best you just go and do it. I knew I wanted to develop this company here. I had to develop an outlet for all this energy we were expending here teaching [through the American Dance Festival, based in Durham, North Carolina]. There are enough dance companies in New York, so I said, 'Well, let me go home.'"

Home for Davis is North Carolina, and despite two decades in New York he still considers himself a Southerner and his family ties to the area remain strong. A Raleigh native, he received the Distinguished North Carolinian award in 1980. In recent years, he spent a considerable amount of time commuting from New York, and traveling throughout North Carolina to conduct residencies for the community outreach program of the American Dance Festival.

Finally deciding to move back home for a while was a relief. "The minute I made that decision, things began to fall into place," he says. "It was as if a burden was lifted from my shoulders." Davis looked down and found that the figures he'd been absent-mindedly scribbling in the sand were completely symmetrical, with an equal number on the right and the left. Right then he realized he had made the right choice.

After two decades of building a life in New York, the move meant leaving some things behind. "I gave up my personal life, my bank account, and any hopes of ever maintaining a totally black moustache," the 47-year-old Davis says, only half facetiously. So far, the change seems to be worth the price. Talking about his new venture, Davis says, "I've gained the world. My feeling is, when you're happy, the universe is yours. You see everything clearer, more in perspective. With work, things will happen."

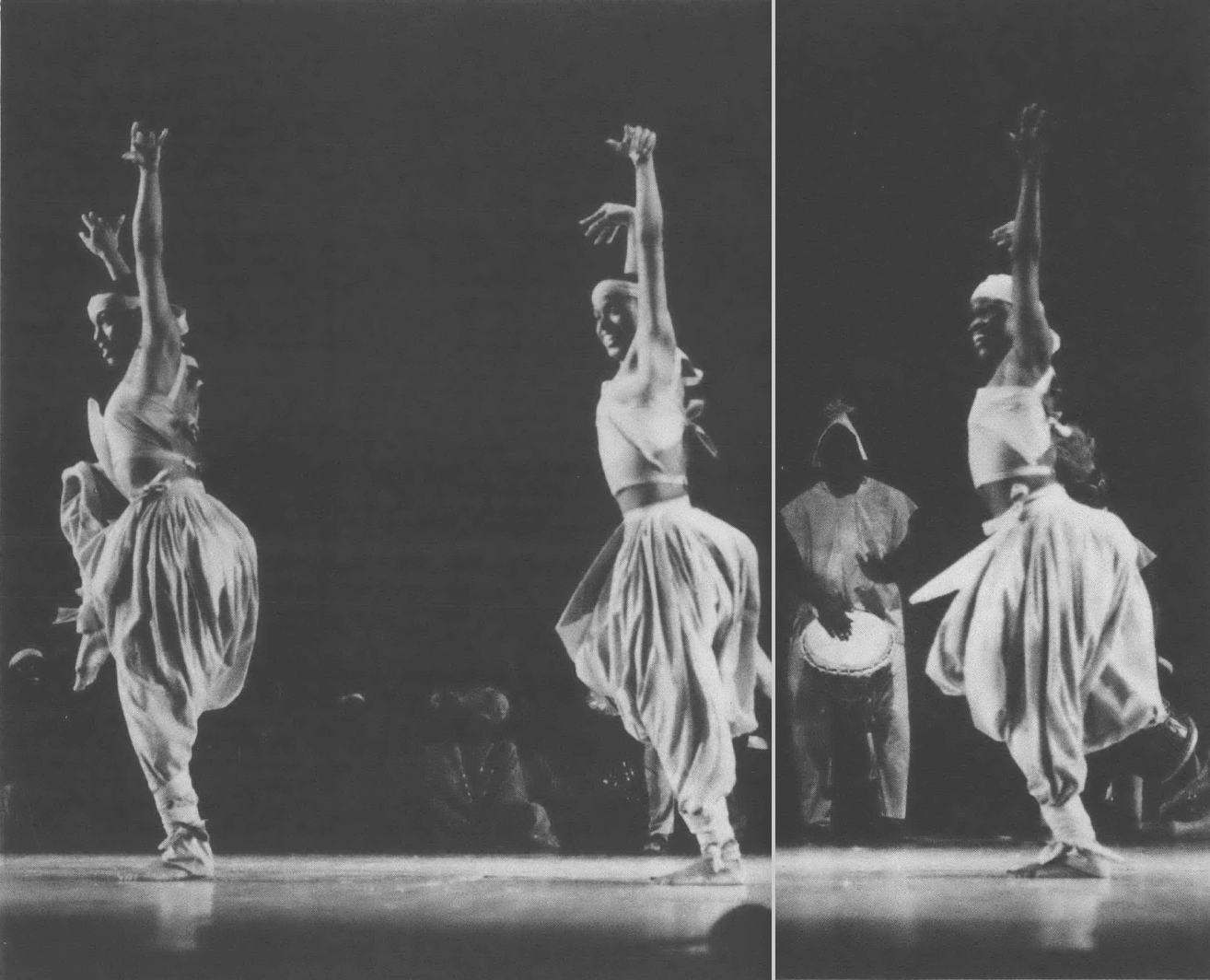

Davis placed the day-to-day direction of his New York company in the hands of Norma Dean Gibson-Woolbright, who's worked with him for 10 years. He commutes frequently to New York to oversee rehearsals and to maintain his ties with the dance community there. Meanwhile, his 18-member North Carolina troupe of dancers and drummers made their first professional concert appearance in Durham in February 1984. Like the New York company, their work emphasizes traditional West African dance forms, but also includes pieces based on the black American experience which incorporate modem dance movement styles.

At the debut, an audience of several hundred turned out to welcome the newcomers, and the dancing was energetic and well-rehearsed. The technical assurance and performing aplomb that characterize the more seasoned New York troupe were missing, but those qualities demand time and nurturance, both of which Davis will provide.

Davis's optimism is not naive, however. Dance companies don't survive in New York on talent alone. It takes guts and savvy to keep an organization afloat for 15 years in that intensely competitive environment. Davis knows his way around city bureaucracies and federal agencies, and fights aggressively for what he wants. The Chuck Davis Dance Company has received support from both the New York State Council on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. They've toured all over the United States and abroad to Western Europe, Yugoslavia, and even the South Pacific under the auspices of the U.S. International Communication Agency. Under his smooth-talking, charming exterior lies a fierce will and burning drive that propels Davis through his endless schedule of rehearsals, performances, and public relations meetings.

Davis demands nearly as much from his dancers as he does from himself, alternately chastising and encouraging to bring out the best in his performers. There is no question about who is boss.

Towards the end of the dress rehearsal for the North Carolina company's February debut, Davis strides on to the stage, towering a head above the men and dwarfing some of the smaller women. His eyes flick over each dancer's costume, making sure that their raffia tassels, cowrie shell ornaments, seedpod belts, and cotton sashes meet his standards for traditional garb. He dismisses anything less as vestiges of "oogaboogaland."

Even after three hours of rehearsal, his dancers listen attentively. What he says is not always pleasant, but it's spiked with earthy humor to get his points across. "I don't want to see movement, I want to see dance," he says, his voice rising. "You men are dancing like dead pigs with maggots in your bellies!" A rag-tag bow at the end of the last piece evokes a torrent of censure. Urging his performers to give 100 percent, he shouts, "If you're dying, you perform. If you are so tired your intestines are screaming, you perform. Smile! Even if you got to buy it at Woolworth's, I want to see some teeth!" Even though it's the night before the performance, he threatens to cut the first part of the show, and schedules an extra rehearsal for the next afternoon.

The dancers and drummers of the fledgling company have responded to his demands, bootstrapping themselves from amateurs to professionals in an amazingly short time. Speaking of working with Davis, dancer Levender Burris from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, says Davis has helped him improve his performance by demanding precise movement phrasing and unswerving concentration in rehearsal. "It's a whole different feeling," says Burris. "And it's great to have [this opportunity] right here in North Carolina. I don't have to go to New York or Los Angeles to get that type of motivation. Chuck makes me dance as hard as I can."

The African- American Dance Ensemble differs from Davis's New York troupe in one immediately obvious way: it is racially integrated. Moving South has, says Davis, freed him of the peer pressure from his black dance colleagues in New York, and allowed him to pick his dancers solely on the basis of talent. Two women in the company are white. "An artist is an artist," Davis states. "People will see them first as black and white, then as a [performing] unit, because the emphasis is on dance''

Davis acknowledges that his point of view is uncommon, and expects some resistance: "I am preparing for the flak that is going to happen, and I'm preparing the dancers for it [in case] . . . there is verbal confrontation." Speaking of his own experiences of racism, he says, "My values are universal. I've been through the hate bit, and I've found it didn't do anything for me, and it didn't do anything for anybody else. As I progressed in my thinking and my growth, I began to see that Africa was the motherland of mankind. We all stem from that one source, and we all have a kinship."

Time after time, Davis has shown his capacity for bringing people of different races, ages, and backgrounds together. In his community work, he does more than simply introduce his audience to African culture. Stressing the communal aspect of African art forms, he brings out the importance of each person's contribution to the success of the whole group. The twin concepts of self-pride and community responsibility give Davis's work an important political dimension.

In his North Carolina residencies, rural audiences respond as enthusiastically as their urban counterparts, and both blacks and whites flock to his workshops, caught up in the mesmerizing rhythms and pulsing energy of the African dances. He is successful with college students; and prisoners take readily to the audience participation portion of the program, joining company members on stage, and clapping and chanting in rhythm.

Children are often a performer's toughest audience, but Davis draws a resounding response from them as well. Young people are attracted to this enormous man who is at once imposing and warmly approachable. And the feeling is mutual. Denise Dickens, director of the American Dance Festival's outreach program, says, "Chuck feels that the older he gets, the more he likes working with the little ones. He just lights up after being with them."

For Davis, working in the schools is a priority. Each visit creates a ripple effect throughout the area. Besides the thousands of students who see his presentations, parents and teachers are also exposed to his work. In Wilson, North Carolina, for example, Carol Blackwood, program director of the local arts council, raves about Davis's residency in the school system there: "I just can't say enough good things. His impact on the community was amazing to me, and I had expected a lot from the residency. His philosophy of love and respect for everyone comes through loud and clear. His residency was probably the best the arts council has ever offered."

Some residencies are one-day events, while others last for several weeks. In Raleigh, Davis recently staged a new theater piece, Babu's Magic, in which a young African village boy uses his special powers and the help of friendly forest animals to save his village from a terrible sickness. For six weeks, 26 students chosen by audition from 10 county schools rehearsed with Davis to prepare the production. Several of these children are so talented, Davis feels, that they may eventually seek careers in the arts. He hopes that for all of them, the discipline that the performance required will be helpful in other school activities.

Davis expects excellent work from his school-aged performers, and they grow to meet those standards. Leah Wise, a member of the African-American Dance Ensemble and a parent of one of Davis's students, commends his work in the schools: "Chuck underscores the power of experiential learning. He's excellent at drawing kids in. As with adults, he gets kids to try things they wouldn't normally do. He's like the Pied Piper."

Davis hopes to expand his work from North Carolina throughout the South. Although there are already a few black dance groups in the region, all could benefit from Davis's long experience and extensive research in Africa. He sees himself as a griot, or teacher and historian, and in that role can surely become a catalyst for the arts in the South, possessing as he does the stature of a national reputation and the charisma of a star.

As a rich repository of black cultural history, the South seems a prime base for his activities. Since black and white cultures have influenced each other for hundreds of years in this region, both races stand to benefit from a deeper understanding of African culture. In his workshops, Davis makes some of these historical links clear. He traces the development of popular black and white social dance styles in America from their origins in ancient African animal imitation dances and acrobatic ritual contests through the Charleston, Twist, and Funky Chicken to today's popular break-dancing. By emphasizing that community sharing and respect for the past are traditional African values, Davis helps to create a temporary community out of a group of strangers.

Davis hopes soon to set up a regional touring schedule for himself and his new company. (They have already performed several times in South Carolina.) Then, after his company's a little more settled, he'd like to organize a regional dance conference so that experienced artists like himself can share their expertise with younger dancers and musicians.

And 10 years from now? With a chuckle he muses, then breaks into a big grin. "I hope to have a villa in Africa and a house in America, and I will commute between the two, overseeing four dance companies, covering the United States, Europe, Africa, and South America — all stemming from the same point of view: that art is to be shared!"

Tags

Jane Desmond

Jane Desmond is currently an artist-in-residence at Duke University. She has taught modem dance technique, ballet, composition, improvisation, repertory, and movement for actors, and has served as a consultant for the New York State Council on the Arts and the North Carolina Arts Council. (1984)