This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 4, "The Chinese: 100 Years in the South." Find more from that issue here.

If the audience had paid money to see the premiere of Mississippi Triangle at the Carnegie Public Library in Clarksdale, Mississippi, some might well have demanded a refund.

Since they hadn't, the nearly 200 Chinese-Americans who viewed the film about race relations in the Mississippi Delta had to content themselves with a closed door discussion with the filmmakers afterward.

When the initial giggles and whispers of "Oh, there's so and so," died down after the film began, some openly wondered why they had opened their doors to the documentary crew. Most said they didn't think it portrayed the progress of Chinese-Americans. Some objected because they thought it left the impression that Chinese are linked more closely with the black community than the white. Certainly the scenes in small country stores and interviews with people of Chinese and African-American ancestry did not sit well with the Chinese audience, most of whom were successful merchants.

In one scene set in an old dark store, groups of Chinese sit around crates used as tables while they set their stakes for mahjong, a traditional gambling game, much as the first Chinese immigrants did. Surrounding this game in progress rest stacks and stacks of Pampers.

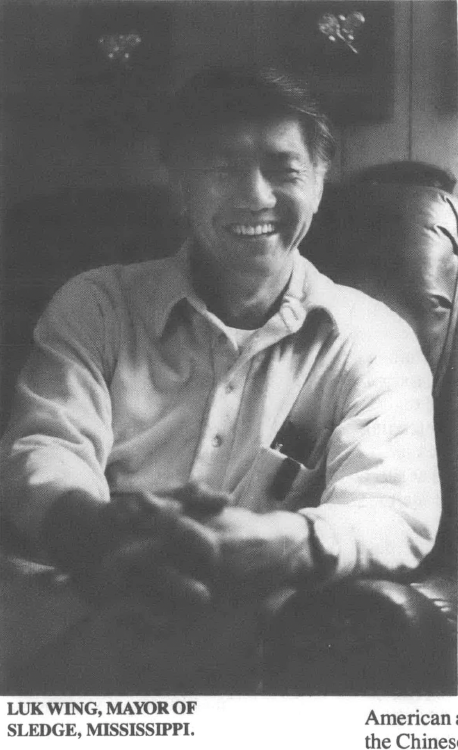

"If you don't know the area, you don't begin to know it from this film," said Hoover Lee, a merchant in Louise, Mississippi. "You would really believe that Chinese still live in the backs of their stores. We have doctors. We have lawyers and we do have people in public office."

McCain Tom, a young man who works as customer information agent at Federal Express in Memphis agreed. "Chinese have more than grocery stores," he said. "It showed the history. It didn't show the present."

Ruth Wong, a student in elementary education student at Delta State University in Greenville, agreed: "It doesn't show how we progressed. Our parents have been very hard working people. It needs to show the sequence, die progress of the Chinese people."

Again and again, the Chinese-Americans in the audience objected that the documentary dwelt on the past and neglected success. Without a doubt, those interviewed in the film tell us that the past has been hard. The negative reaction from members of the Chinese community wasn't unexpected. Before the showing, rumors had spread through the community that poor Chinese and black Chinese were depicted in the film, much to the chagrin of some community members who wanted to see images of success.

"Like all immigrant groups — the Italians, the Irish, the Greeks, the Jews — the Chinese don't want to talk about suffering," film producer Christine Choy explains. "They don't want to review their hardships. They only want to talk about how they made it." Choy adds that her desire to make the film goes back to her days in New York's Chinatown, where, as a Chinese immigrant, she was confused by a multi-ethnic society and adults who refused to talk about the past. "Being Chinese, I have always felt that I was an in-between," she says."

Many Chinese also sharply criticized the inclusion of an interview with a woman who, when asked to define interracial relationships, fumbled for words and was unable after several false starts to articulate her feelings about the subject. Since she is a well-educated woman, an assistant principal in one of the schools, they thought this depiction of her was unfair. But Choy thinks it simply shows a woman reacting in a very honest way to an obviously disturbing question.

Equally disturbing to the audience was the film's suggestion that Chinese associate more with the black community than the white. In an angry criticism of one scene where a young black man is helping a young Chinese woman with her car, one Chinese man said disgustedly, "It even makes it look like we need blacks to help us fix our cars."

The film shows a young Chinese-American couple getting married in a Protestant ceremony that could have been captured by Norman Rockwell. The bride wears a white gown and a veil across her face. The church is packed with well-wishers. The organist plays inspiredly. After the ceremony, the young woman exchanges her stiff white dress for chung san. She then performs a tea ceremony before the father of her new husband.

After the film, an old man said he was angry because the shot of the young woman changing from western to Chinese clothing showed her stripped to her undergarments. "I didn't come here to see an x-rated show," he said. He is the woman's grandfather.

Hoover Lee, who became the first Chinese mayor in Louise, stood by his criticism that the film spent too much time looking at the "down side of things — gambling, pool rooms, rundown stores." But he tempered his initial opinion and later stated that he realized the filmmakers were trying to portray three races, not just the Chinese.

"You've got to remember that the Chinese people in the Delta are very conservative," said Lee. "As far as the operation of the grocery, the film gave a true idea of the operation. Our business in the Delta is mainly from the blacks, who make up most of the population, especially in the smaller towns."

Choy emphasizes, "This film is not about success and failure. It is a look at race relations in a tri-racial situation. In most films about race relations, it is always two groups, black versus white, Jewish versus WASP, Hispanic versus white. It's more complex than that," she says.

The title of the film is not an accident but a play on words. It is a way to look at three different communities within the Delta. The blacks, the Chinese, and the whites are each a point on the triangle. Delta, in turn, is the Greek letter shaped like a triangle and describes the shape of the land at the mouth of a river.

Most geography books don't mention the Chinese-Americans who settled in the northwestern part of Mississippi. Yet, there are 2,000 of them, in towns like Clarksdale, Louise, and Greenville. Most are now second- and third-generation Americans. And members of the third generation speak as much Chinese as third-generation Poles in Chicago speak Polish: not much.

"Chris [Choy] had come to the Delta and tried to do a sensitive portrayal of the culture, focusing on the Chinese," Worth Long remarked at the community meeting with filmmakers following the premiere. "I didn't want people to leave that room without recognizing the significance of their even being there." So Long asked the question. "Why is it that we could not have this meeting here 20 years ago?"

One answer is that 20 years ago blacks and Chinese were not let into the library, where the film was shown.

The most valuable contribution of Mississippi Triangle is the dialogue it generated, Choy believes. "What is important is the way people think. The film became the focus of a debate, and when that happened, the film became secondary."

Whether the film reinforces stereotyping, as the Chinese in Clarksdale said, whether it changes minds or merely gives us food for thought, remains to be seen. In any case, anyone who sees it will carry away some sharp images, like that of the bent-over Chinese man singing an eerie song that no one on the Delta will sing for much longer.

Tags

Adria Bernardi

Adria Bemardi is a freelance writer now living in Memphis. She was formerly a reporter with the News Bureau of Chicago and an editor with UPI. (1984)