This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 4, "The Chinese: 100 Years in the South." Find more from that issue here.

The year is 1963. Christine Choy has just been uprooted from her Shanghai home to join her father, whom she has not seen in years, in South Korea. Bom of a Chinese mother from Vladivostok and a Korean father who was exiled to China during the Japanese occupation, Choy has long been a sojourner between cultures.

At the same time, thousands of miles away, Worth Long, son of black sharecroppers and an activist in civil rights struggles since the Little Rock school crisis of 1955, travels to Mississippi. The black community has organized a boycott to challenge the entrenched segregated economy of the South, and Long has been called in as a mediator. That action, taken not against whites but against the Chinese grocers of Greenwood who serve local sharecroppers, highlights the precarious position between black and white that Chinese in the Delta have occupied for generations.

Alan Siegel is a Jewish kid in Levittown, New York, the prototype of the rows and rows of modest, treelined streets of tract homes which stretch out across all of post-50s Americana. But this benign suburban exterior belies the transformation in racial politics brewing throughout the nation. Even as a high school student, Siegel senses the urgency of the times and becomes an activist with the local Congress of Racial Equality.

Almost two decades later, the lives of the three converge and Choy, Long, and Seigel travel to the Mississippi Delta to document the history and continuing story of its Chinese community. In the fall of 1983, after six years of work, they completed Mississippi Triangle, a film depicting the intertwining lives of the Chinese, blacks, and whites in the Delta.

The Delta, the filmmakers, and America had all changed markedly in that 20-year span. Choy's journey took her from Korea to New York's exclusive Manhattanville College in 1965 during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. But that struggle was as alien to her then as the pristine Catholic women's school she attended. "When I arrived I didn't know about the Civil Rights Movement. And I didn't realize the reason I got a full scholarship was because the blacks had marched to demand equal rights and open admissions for minorities," she recalls.

As the '70s approached, Choy's expanding awareness of the civil rights and anti-war movements led her to Newsreel, a loosely organized group of people who identified themselves as political activists, rather than filmmakers. The group produced roughly hewn and controversial documents on political movements of their era, sending film crews to Vietnam and Cuba. Siegel, a founding member, and Choy reconstituted the group in 1971, renaming it the Third World Newsreel.

Choy's first films centered on blacks in America, and included the award-winning documentary, Teach Our Children, about the Attica State Prison rebellion; she co-produced the film with Susan Robeson, Paul Robeson's daughter. But as a new vitality emerged from Asian-American writers, artists, and filmmakers, she began to explore her own heritage. "I wanted to make films about Asian-Americans to support all this energy," she explains. In 1978 while shooting a film about Asian-Americans in the Delaware Valley, she and Siegel met a Chinese-American student who talked about growing up in the Mississippi Delta and the Chinese community there.

"No one had ever heard of it," said Choy. Intrigued, they searched for more information but came across only one comprehensive resource, James Loewen's book, The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White. Third World Newsreel felt this was a story that had to be told.

After receiving funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Third World Newsreel set the project in motion in the fall of 1980 with an extensive research phase. The pre-production team included Chinese-American filmmaker Yuet Fung Ho who, having grown up "in the back of a grocery store" in Hong Kong, felt a particular affinity for the families of Mississippi who shared her background. African-American film historian Pearl Bowser unearthed rare archival footage of the life in the Delta during the early 1900s and during the Civil Rights Movement.

Assisted by an advisory board of scholars headed by Loewen, the team's research unearthed a complex picture of tri-racial social relations. Excluded from white society and from any real civic power, the Chinese, like the African-Americans who preceded them, set up parallel institutions to meet their needs. Those institutions in many ways reflect the influence of the dominant culture. In the Delta there are white, black, and Chinese cemeteries and Baptist churches. The Chinese have assessed the lack of power and resources in the black community and do not want to be identified with the black under-class. Yet the Chinese store owner, who remains a pivotal figure in his own community, must maintain cordial relations with the blacks who are his major customers.

As art imitates life, the filmmakers crafted a production philosophy and process as complex as their subject matter. Thus, what began as a simple documentary of the Delta Chinese evolved into an intricate analysis of race and class. "You couldn't talk about the role of the Chinese without discussing blacks and whites," declares Siegel. "The theory of the melting pot is ludicrous," adds Choy. "The races do not exist in harmony. So I wanted to look at those differences, and have each group express its own point of view. This concept made the process of the film very important. That's why we shot it with three crews: one black, one Asian, and one white."

Siegel, who directed the white crew, explained that the decision to use a tri-racial crew was both philosophical and practical: "In the South there's not a whole lot of substantial communication between the races." By using three separate crews the filmmakers hoped to "be able to get more insight and an honest picture of the way people thought."

The three-pronged production process involved heavy aesthetic coordination in order to preserve a stylistic unity. "It's like a quilt," Choy observed. "Each piece is a different fabric. But in a quilt sometimes there is repetition." Into the fabric of Mississippi Triangle these filmmakers have woven the parallel rituals of funerals, religious ceremonies, the education of the young, cotton-farming and work patterns, representing a full spectrum of Delta life.

Like most Third World Newsreel productions, the story is told completely through the voices of Mississippi people, without analysis by "experts" or the intrusion of a narrator. Project staff conducted over 200 oral histories and interviews. Personal histories of older residents reconstruct the patterns of migration and work that brought the Chinese to the Delta.

Arlee Hen recounts how her father's name was arbitrarily changed when he arrived in Mississippi as a contract laborer. "My father's name is Wong On. He acquired the name Sing because they had a company they called Sing. Everybody was Sing, but they weren't really Sing, you know. After he stayed there a while he worked with them coming to Mississippi to put down the first railroad tracks for the trains to come this way."

James Chow remembers, "They say we got a good opportunity to make some money. So we go to Mississippi to pick cotton. So they pay so much a pound or so much a day. They said we could make more money if we picked more cotton. They gave them so much a year on how much cotton they sold and how much cotton they picked and they give 'em very little money. They gave 'em just enough to eat and then a little bit of money to spend during the Christmastime. That's about all. But the people, they tell me, that they not get what they supposed to get. 'Course the farmer's the one that got rich. They got it all."

Arlee Hen adds, "They couldn't get a fair price for the cotton they raised, so they rented a boat or something and went to New Orleans and sold it themselves. And when they came back with the money, they stopped in Greenville and started stores."

A common history of exploitation is Worth Long's starting point for exploring the intersection of the Delta's African-American community with the Chinese. Long, a leading expert in the field of black folk culture travels many of the same roads he followed as a SNCC organizer, struggling now to preserve and celebrate African-American history and heritage.

A front porch was the setting for an interview with a former farmworker. "I'm John Dorsey. Bom in 1908, fifteenth day of October. Started off working 50 cents a day. One of the best mule plows in this country. They had me plowing their winter crops. And I'm still on W. A. Percy's farm, Trail Lake, Mississippi. I work in the cotton field all day, come to the gin six o'clock in the evening, work til two o'clock in the morning. Go back on that cotton picker. Back in those times, when you had that one row stuff and two row stuff, you was working from sun to sun. Some got 50 cents a day, some got 75, some got a dollar a day."

Cotton commerce as the region's economic lifeblood shapes Alan Siegel's approach to the Delta's tri-racial society. He defines power relationships using a wordless, visual dialectic. In a typical scene, a white cotton grader decides the quality of each bunch of cotton and the black worker puts it into the right box. In scene after scene whites make the decisions and the blacks follow orders; whites do the thinking and blacks the manual labor.

The monolith of black-white segregation would barely budge for the Chinese. In 1924, 30 years before the Brown decision, the Lum family filed suit to desegregate the public schools. "At that time, the Immigration wouldn't allow them to bring their wives over," Berda Lum explains. Martha Lum adds, "And I guess they couldn't associate with the white women, so they took black women." Berda Lum continues, "As a result, they had children who couldn't go to school.

"So they fought it to the Mississippi courts. We lost the case there. They said that we could have our own school. And we could keep the Negroes out, all the Caucasians out, and only have it exclusively for Chinese. Well, that was one thing that we did not want. We did not want segregation. We wanted to go to the schools like all the rest of the Americans go to school. So, therefore, my dad packed up and we moved to Lakeview, Arkansas."

The film's emotional core is in the words of these Black Chinese who faced the same racial strictures as their mothers and were similarly ostracized by the Chinese community, along with their fathers.

Speaking of the mixed marriages of the older generation, James Chow says, "The younger generation don't do that any more. They feel like they been segregated because of that, you know, of the older people's fault — to marry the mixed."

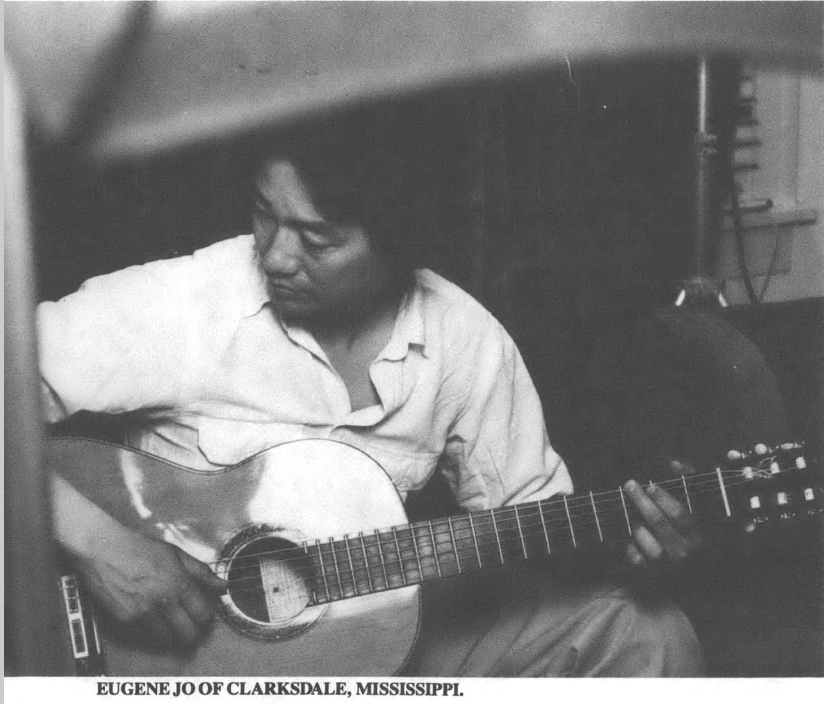

Ludwig Goon, cinematographer for Mississippi Triangle, has experienced the isolation of such a mixed family. His father Henry would normally be on the city council or mayor of the city, according to Long. "Henry Goon is a scholar, a grocery owner, the father of successful children. Every Sunday, Chinese neighbors would drive to his home to get translations and letters back home written in Chinese, but they would park their cars far down the street so people wouldn't know of their visit." Goon is married to a black woman.

In one scene in the film, Henry says to his son, Ludwig, ''When you think enough of a person, well, you begin to have feelings for a person. Sometimes you don't look at a person on the surface. Because they say beauty is skin deep. Now what I have done is something different, you see? But I'm still Chinese."

It was no easy task for Choy to bring out the negative aspects of the Chinese community displayed in their treatment of the black Chinese and other chauvinist behavior. "Asian-American filmmakers have tried to promote unity with positive films on Asians because the images of Asians have been so bad. But we've never really looked critically into our own community," says Choy.

A particularly sore subject is the Chinese apathy toward black social struggles. Sam Block and the other black activists who boycotted Chinese stores in 1963 saw Chinese support as crucial. "Sam didn't want economic support from them but vocal support. He wanted the Chinese to say they were being mistreated too." The Chinese were clearly relegated to the low end of the social stratum and considered "no better than black," Worth Long explained.

Luk Wing, the first Chinese mayor in Mississippi, acknowledges that "the Civil Rights Movement helped the Chinese to attain certain status among the white world. Whereas we didn't have anything to gain in the black world, 'cause they didn't have nothing for us to step into. We didn't march."

"You have to put these attitudes in a larger context," Choy reasons. "It's not only an individual's fault for not getting involved, but a function of the American social pattern. Mississippi was built for two races: master and slave. Chinese were a third element. They allied with whites because that meant they were allied with the power structure."

In the black Chinese, Choy found a sensitivity to the black experience in the South that approximates her own. Through them she was able to articulate a keen sense of both the conflicts and the depth of understanding which emerge from a transcultural experience. When Choy's crew shot scenes with Arlee Hen, the daughter of a Chinese immigrant railroad worker and a Mississippi African-American, the crew had to sneak back to her home after pretending to leave town so that the Chinese community would not be offended that she was being interviewed as one of their own.

Mississippi Triangle has had international screenings and will continue on a tour throughout the South. Third World Newsreel hopes to distribute the film in major cities across the country and on public television. Distributing an independent film, particularly one about race relations in the South, is no easy task in a media atmosphere which emphasizes entertainment and flash. But the filmmakers are determined to get the film into theaters; on the air; and in any small town, community center, school, church, or hole-in-the-wall where people could see it. "I'm trying to say something to young people," Choy says. These people in the Delta are dying out and it's our responsibility to document their history. Your mother, father, grandparents — there's so much history to be told."

Renee Tajima

Renee Tajima is associate editor of Independent Film and Video Monthly and LPTV Currents and she is an independent producer. (1984)