This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. XII No. 6, "Liberating Our Past." Find more from that issue here.

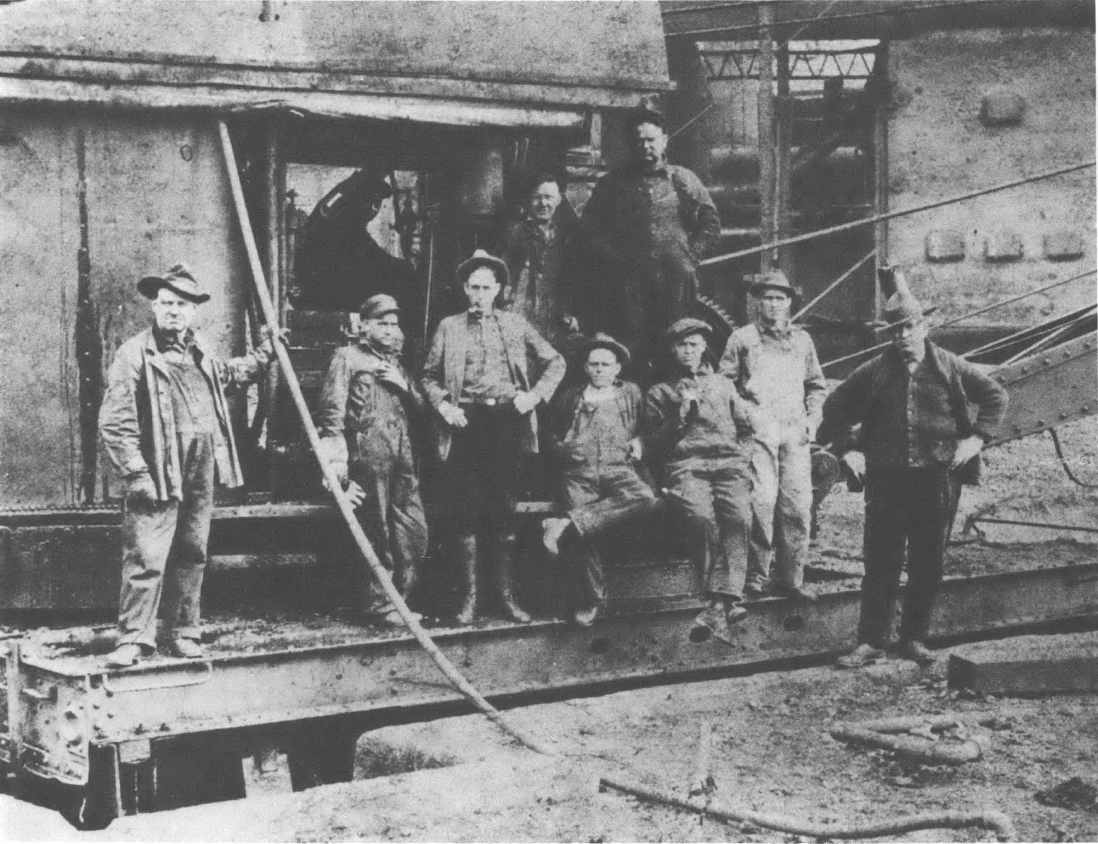

On Labor Day weekend, 1983, Sloss Furnaces opened its gates to the people of Birmingham, Alabama. Six thousand citizens, including former workers and their relatives, came to examine the site where thousands of men had worked over the years between 1881 and 1971.

When the Jim Walter Corporation closed the furnaces in 1971, they deeded Sloss to the Alabama State Fair Authority with the hope that it could be made into an industrial history museum. The State Fair Authority did not consider the preservation of the furnaces feasible, and instead proposed their dismantlement.

The threatened destruction of Sloss Furnaces resulted in great public outcry. A group of citizens, including many former employees, organized the Sloss Furnace Association; through their work the furnaces were deeded to the City of Birmingham, and city voters passed a special bond referendum which raised funds for preservation and development of the historic property. In 1979 the U.S. Department of the Interior designated Sloss Furnaces as a National Historic Landmark.

Today Sloss serves as an important symbol of Birmingham's past, as a museum, and as a popular community center. The work of reconstructing the past has begun in earnest. Unfortunately, few written manuscripts have survived, company records have never been located, and public archival materials are scarce. The absence of these written materials about Sloss Furnaces has forced researchers to rely heavily on oral histories, material artifacts at the site, maps, and — as is done here — entries about individual workers in city directories and the manuscript census.

Data gleaned from city directories and the manuscript census yields a composite picture of workers' lives in a Southern industrial city. Patterns of work, family, and community become clearer as tabulated figures provide details about age, race, and household size. Home addresses provide clues to neighborhood composition, and job titles flesh out the meaning of the ubiquitous term "laborer: " We offer this as a snapshot of Birmingham workers in 1900, and as a starting point for further analysis, and as an example of what can be done in other cities.

Birmingham, Alabama, was founded when railroads built after the Civil War connected the outside world to the rich yet untapped coal and iron ore deposits of the Jones Valley. At the intersection of two rail lines Birmingham began in 1871, and its new iron furnaces and steel mills soon attracted workers from all over the U.S. and Europe. Saloons flourished and the daily brawls and shootouts of rough settlers gave the New South boom town the nickname, "Big Bad Birmingham."

This study began as an investigation of a "company town" on the edge of Birmingham — specifically the area known as Sloss Quarters. Colonel James Withers Sloss, one of the city's earliest land speculators and railroad leaders, formed the Sloss Furnace Company in 1881. By 1900 his reorganized Sloss-Sheffield Steel & Iron Company (SSS&I) owned five coal mines in Jefferson County and two furnaces on the eastern and northern fringes of the city.

At the turn of the century Birmingham encompassed only a small area and most people walked around town. The city was divided into quadrants by a railroad line and a perpendicular main street, but a number of new suburbs hinted at the area's future growth. North Birmingham, Avondale, and East Birmingham were primarily industrial suburbs with small houses. East Lake, Woodlawn, Elyton, and Smithfield were residential suburbs with larger homes located further apart.

Many of the area's iron and steel companies, and certainly the coal mining operations in Alabama, owned and operated worker housing and commissaries. Their operations fit the pattern of the traditional company town: a dense cluster of sub-standard housing for longtime workers tied to a single corporation. According to the 1900 Birmingham City Directory, however, only 35, or one-third, of the household heads living in Sloss Quarters were employed by SSS&I. The other 69 workers living in the Quarters included 19 female laundresses and male industrial workers employed by other companies. The presence of so many non-Sloss workers in company-owned housing challenges the concept of a company town and raises a number of questions. Who were the Sloss workers? Where did they live, if not in the Quarters? And did the company maintain control over their lives and mobility?

No company records presently available answer these questions. City directories and census manuscripts are two useful sources for identifying Sloss workers by residency and occupation and for providing specific information about their families. A thorough search of the names of workers in the 1900 city directory identified 579 SSS&I workers and executives, of whom 437 were black males and 142 were white, including one woman, a stenographer. Nearly one half of the white men and one fourth of the black workers were also listed in the 1900 manuscript census. (The higher percentage of whites recorded in both sources reflects the fact that whites more often held skilled jobs, and blacks were more likely to live on alleys not included in the census.)

The profile of the Sloss workers that emerges from the census and city directory shows a work force of predominantly black laborers and exclusively white managers. The job segregation of workers by race is clearly apparent. Assuming that skilled, unskilled, and supervisory workers were found in both the furnaces and mines, we see that 98.1 percent of the blacks and 55.2 percent of the whites were involved in hard, physical labor; while only 1.9 percent of the blacks (two office "runners") worked outside the furnaces and mines, 44.8 percent of whites worked in other areas. Further, if we focus on the 133 skilled and unskilled workers listed in the census (see Table 1), it is clear that almost 80 percent of the hard labor was performed by black men.

The census records another group of workers engaged in hard labor: nearly 500 blacks and a few whites housed at the "SSS&I Convict Prison" in North Birmingham. Thus in 1900 nearly one half the Sloss workforce consisted of convict labor. Most of these men were arrested on charges of vagrancy and leased by Alabama counties to SSS&I for nine to ten dollars a month; the workers themselves received no money.

The census also allows us to ascertain some personal information about free Sloss workers — factors such as age, literacy, place of birth, and household composition. The average SSS&I employee was 35.3 years old (36.1 for blacks and 34.2 for whites), yet they lived in a city that had been a cornfield only 30 years earlier; essentially, they all came from somewhere else (Tables 2 and 3). All black workers, and all but one of their parents, were born in the South, mostly in rural Alabama. In contrast, only 41.8 percent of white workers were born in Alabama, and a fourth of their parents were foreign-born.

The continuous mobility of Sloss workers is demonstrated by the fact that a majority listed in the 1900 city directory do not show up in later editions. Indeed, some workers identified in both the 1900 directory and the census listed different addresses in the two documents, indicating a change of residence in the six-month interval between the preparation of these two surveys.

Census records provide abundant additional data on family life. For example, nearly three-fourths (72.2 percent) of black workers and three-fifths of white workers (58.2 percent) were married; the average number of years of marriage ranged from 11 for blacks to 14 for whites. None of the wives of white Sloss workers indicated an occupation, while 19.2 percent of black wives worked for wages, usually as laundresses, cooks, and house servants.

We often think of the typical 1900 family as including an assortment of grandparents, in-laws, cousins, and uncles, as well as non-relatives such as boarders and servants. We might also speculate that black households among the Sloss workers were larger than white ones since blacks were closer to their birthplaces and families. But Tables 4 and 5 demonstrate that the average white family with children and the average white household were in fact larger than their black counterparts (4.6 whites vs. 3.3 blacks for families, and 5.3 vs. 4.7 for households). Further, most households included at most only one person who was not part of the nuclear parent/child family. About one in four families of both races included a relative in the household, generally the spouse of a married child. Few white families had boarders — less than 9 percent — while almost 26 percent of black households included boarders. Few families of either race had servants: three black households out of 108, and seven white households out of 67.

Because the 1900 census listed by name and age all children living in a home, it is possible to identify the number of adult children who remained at home with their parents: 8.1 percent of black families with children included at least one child aged 21 or older; in sharp contrast, 48.2 percent of the white families with children had a child aged 21 or older. Many of these white adult children were unmarried men living with their parents, which explains the higher percentage of single Sloss workers among whites.

A comparison by race of the 27 single workers who lived with their parents illustrates significant class distinctions among Sloss employees. Of the six who were black, all were unskilled laborers, with the exception of one clergyman. The average age of black sons was 16.8 years and 55.3 years for fathers. Five of these six sons lived in rented housing. Thus, most single black SSS&I workers who lived at home were younger boys who either supplemented the income of their lower-income family or attempted to replace a deceased father's earnings.

The 21 single white workers living with their parents present a far different picture. Ten were skilled laborers, and their fathers were either skilled laborers or middle-class tradesmen. The remaining 11 sons were office workers or professionals, and their fathers were professionals, federal employees, or self-employed. These two groups of whites show no significant differences in the ages of sons (23.1) or fathers (54.9), and there is an even division of owned and rented homes. Most working white sons living at home were older than their black counterparts, and either carried on a tradition of skilled labor or performed white-collar jobs as members of families which were comfortably middle class.

This review of working sons also indicates that no strong company ties compelled relatives to work for Sloss. In feet, the data reveal only two instances where both a father and son worked for SSS&I. In only four other cases did a family have two sons working at Sloss.

The absence of paternalistic or traditional company-town control exerted by SSS&I is further indicated by the residential patterns of its employees. While there was a high concentration of SSS&I workers near the North Birmingham and City Furnaces, company workers lived throughout the city and in outlying areas. Neighborhoods were generally integrated, although the alleys which bisected certain blocks usually housed only black families. Table 6 shows that while the western sections were least populated, the remaining parts of greater Birmingham were home for a variety of black and white Sloss workers.

It is important to note that the majority of SSS&I workers rented or boarded, especially if they lived inside the city limits. Only 4.6 percent of blacks and 37.3 percent of whites owned homes, primarily located in the suburbs of East Lake, Avondale, Woodlawn, and North Birmingham. Among blacks, 82.4 percent rented homes and 12 percent boarded with other families or in boarding houses. Among whites, the figures were 49.3 percent and 10.5 percent respectively. Once again, the evidence gives an impression of a highly mobile population.

We see, then, that the data describing Sloss workers in 1900 contradict the notion of an urban industrial labor force locked in a company town. There is no indication that SSS&I controlled where or how its workers lived, nor that it provided educational, recreational, or residential services which increased the workers' dependency on the company. (It is not possible at this time to compare the prices at the Sloss commissary with those at other stores to determine if the commissary benefited or indebted Sloss workers.) Most striking is the high mobility of Sloss employees, demonstrating that workers were not tied to SSS&I, a particular house, or even the city of Birmingham; the only source of stability and continuity for workers revolved around their families, with small, single-family households the norm. In all other areas, we see a highly mobile urban population which stands in sharp contrast to the typical company town and workforce.

Tags

Barbara J. Mitchell

Barbara Mitchell is a graduate student in history at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. (1984)

Mary Frederickson

Mary Frederickson is a graduate student in history at the University of North Carolina. She is currently writing a doctoral dissertation on the Southern Summer School. (1977)