This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. XII No. 6, "Liberating Our Past." Find more from that issue here.

The following selections come from a work provisionally titled Tombee: The Life Story and Plantation Journal of Thomas B. Chaplin (1822-1890), to be published in the fall of1985 by William Morrow.

Tombee combines a biography of an unlucky slavemaster and cotton planter from St. Helena Island, South Carolina, with the journal he kept between 1845 and 1858. The biography traces the social and ecological history of St. Helena Island from the day Europeans first laid eyes on it to the moment Chaplin left for the last time, in 1885, old, defeated, still searching for the peace of mind that had always eluded him.

This history is the backdrop for an intense family drama involving three generations of Chaplins. Thomas Chaplin's mother, Isabella, married four times and accumulated five plantations and nearly 300 slaves, making her one of the richest women in America on the eve of the Civil War. Her third husband was Thomas's father. Her fourth husband was a bankrupt pharmacist and portrait painter 20 years her junior. For 25 years, right up to the day that Sherman's army liberated the slaves of the lower Carolina coast, Chaplin battled his stepfather over his mother's wealth and affections. He himself had two wives and seven children, six of whom died before he did. The generations were linked by land — but the land was lost, either swept away "by the great blast of ruin and destruction," the Civil War, or seized to pay debts in the bitter aftermath.

Chaplin's Journal offers rewarding entry into the last years of an American aristocracy, recorded in complete innocence of the changes ahead. It contains a social history of the Carolina Sea Islands during the second golden age of cotton. It furnishes an extensive account of the Sea Island cotton trade and a relentless, if inadvertent, study of the dull horror of plantation slavery.

The first excerpt includes two sections from Chapter II of the biography, dealing with the origins and spread of Sea Island cotton and changing patterns of land use on St. Helena Island.

The search for a new staple intensified after 1786. Planters in the Southern states and Louisiana began experimenting with varieties of cotton. An international traffic in seeds broadcast strains of cotton from Siam, Egypt, Malta, Cuba. The cotton that first took hold in South Carolina was a long-staple, black-seed variety that migrated to the Sea Islands from Georgia, which had received it from the Bahamas, where it had drifted from Anguilla, in the Leeward Islands. Nor was it native to the West Indies, but had journeyed there from the Near East, possibly from Persia. William Elliott of Hilton Head Island raised the first successful crop of long-staple cotton in South Carolina, in 1790. Great fortunes awaited those who followed his example. Estates that had risen and fallen with indigo grew rich again. Thomas B. Chaplin's grandfather probably built the Big House at Tombee with the profits from his first Sea Island cotton crops.

Cotton is a soft, white, downy substance made of the hairs or fibers attached to the seeds of plants of the genus Gossypium. When carded or combed to its full length, the fiber of Sea Island cotton measures one-and-a-half to two inches long, compared to a range of five-eighths to one inch for common upland or short-staple cotton. The fineness is reckoned by the number of hanks that can be spun from one pound — a hank being a length of yarn 840 yards long. Sea Island cotton normally spun about 300 hanks to the pound, about twice the number for short-staple cotton. The longest and finest of the long staples was said to have spun 500 hanks. Because of its superior strength, long-staple cotton was used for making the warp, or longitudinal threads, of many woven fabrics. It went into the finer cloths which adorned the wealthy classes of Europe. The entire Sea Island crop was shipped abroad, most of it to the mills of Lancashire, none to the mills of New England.

Only the Sea Islands of South Carolina and the northernmost islands of Georgia produced the finer varieties of Sea Island cotton. The same seeds planted on the mainland near the coast yielded a less fine but still valuable cotton called Mains or Santees, depending on the location. Sea Island seeds sown inland yielded a coarser fiber, less profitable than the short-staple cotton that could be raised in the same place. A variety of long-staple cotton grown on the islands off the lower coast of Georgia and northern Florida passed for Sea Island, but it was an inferior fiber and brought less than Mains or Santees.

Though Sea Island cotton commanded at least twice the price of upland cotton, and usually much more, it bore considerably less fruit and produced only about half as much lint to the acre, and then only on well-fertilized fields. A great deal more labor was necessary to grow, clean, and pack a pound of Sea Island. The bolls opened slowly, and the picking season could last six months. Being so long in the field, the cotton was vulnerable to bad weather. Sea Island cotton fields needed heavy manuring, the plants needed many hoeings, and the lint needed special handling during its preparation for market.

Before 1805 the only manuring on the Sea Islands consisted of moving cow pens over potato patches and spreading barn manures. Each year, cotton would be planted on a different piece of ground, to rest the spot where it grew the year before. This "absurd doctrine" of resting arable land ended with the discovery of a cheap, abundant fertilizer — salt marsh mud, the sediment-rich peat that lay at the doorstep of every Sea Island plantation. Salt marshes are the most fertile and productive parts of the earth. They contain more organisms per square foot and are capable of nourishing the young of more different species than any other soil. Marsh mud added organic matter to the sandy cotton fields and supplied vital elements like phosphorus and magnesium. Salt marsh grass was good for littering stables and stock pens; its judicious use could double the quantity of animal manure. Or the grass could be turned into the ground directly. Planters experimented with mixtures of marsh mud, stable manures, and vegetable composts. They carefully guarded their formulas for the most efficacious concoctions. During the first golden age of cotton, which ended in 1819, many Sea Island fortunes were built on foundations of mud and manure.

Once it was proved that the long-staple cotton would flourish in the warm island soil, its cultivation spread swiftly along the coasts of Beaufort, Colleton, and Charleston Districts. In 1790 the Sea Island cotton crop of the United States was under 10,000 pounds, or just about 30 bales. By 1801 it had soared to 8.5 million pounds, or about 22,000 bales. In the space of 11 years — three or four years, really, once the knowledge caught on — thousands of laborers had learned to make a new staple crop, an active market of buyers and sellers sprang into operation, and a vast exchange of money, seeds, and information had thrust some fallow islands off the malarial coast of South Carolina into prominence as producers of the world's finest cotton.

The Sea Island crop of 1805 rose to 26,000 bales. Twenty-five years later, the size of the crop was about the same. While the upland output increased phenomenally right up until the Civil War — with the exception of two brief recessions in the 1840s — Sea Island cotton approached a limit early in the century. It was restricted to the soil and climate of the Sea Islands, and the crop could expand only if more acres on the islands were planted. For this to happen, profits would have to justify the expense of preparing the less accessible and weaker lands or impounding the few small interior marshes. Such enterprises generally were not attempted between 1819 and the late 1840s, the era of the Sea Island cotton depression. As a proportion of the total American crop, Sea Island declined steadily. It accounted for 20 percent of the total in 1801, but a scant 1 percent 40 years later. It had become strictly a luxury item, "almost entirely consumed in administering to vanity."

For the first six years of the nineteenth century, prices for Sea Island cotton at Charleston ranged between 44 and 52 cents per pound. Planters were profiting from the boom in English cotton manufacturing, from technological advances in looms and new methods of dyeing and printing. Prices slumped to about 25 cents a pound by 1809, then rose again the next year when, perhaps coincidentally, a labor-saving lacemaking machine was invented in England. The War of 1812 stimulated construction of cotton mills in New England, but none that handled the long-staple. Prices for Sea Island cotton sank to 13 cents in April 1813 but revived after that, reaching a heady 50 to 55 cents a pound at the end of 1815. High prices held for two-and-a-half years, culminating in a "frenzy of speculation" that peaked at 75 cents a pound in August 1818. The price differential between Sea Island fine and the better grades of upland cotton was nearly half a dollar. Prices fell suddenly, touching 30 cents a pound in December 1819. They kept falling,1 and in the spring of 1822, when Thomas B. Chaplin was born, prices for common Sea Island cotton hovered near 25 cents a pound.

All of the cotton raised on St. Helena Island went to market by boat. The island is shaped like the body of a blue crab, and most of the plantations were distributed around its circumference. A few were tucked against the branches of creeks that flowed into the island's interior, and three or four plantations were landlocked. These had to share a neighbor's boat landing, using oxcarts to haul the cotton bales to a dock. Plantations were separated by woods, hedges, creeks, ditches, and fences. They tended to be rectangular in shape, with a short side on the water, stretching lengthwise from the water's edge toward a belt of woods that extended across the center of the island. Tombee was an exception, a crown-shaped tract — looking at it from the northeast — bisected by a branch of Station Creek.

Tombee contained 376 acres of improved and unimproved land. It was larger, in 1860, than 33 plantations on St. Helena Island, and smaller than 21 others. More than half the plantations contained between 100 and 300 acres. Eighteen plantations had 500 acres or more, and two had more than 1,000 acres — Coffin's Point, on St. Helena Sound, and Frogmore, on the Seaside, both belonging to Thomas A. Coffin. St. Helena Parish had the lowest ratio of improved to unimproved acres — about seven to five — of any parish in the Low Country. At the end of the slavery era, there was unused cultivable land on virtually every plantation on St. Helena Island. Most fields were in the shape of large squares intersected by cart paths and drainage ditches. The fields were enclosed by costly rail-and-pole fences or by natural divides or obstructions capable of keeping out livestock. By and large, the plantations were rectangular and open; the fields were square and closed.

Two roads traversed the island, one running southwesterly from St. Helenaville, the other running more westerly from Coffin's Point, about two miles below the village, with the two roads meeting above Lands End, just west of Tombee. A fork of Lands End Road, or Church Road, as the upper, more northerly road was called, led west to the Ladies Island ferry. The lower road, called Seaside Road, crossed the rich Coffin, Fripp, and Jenkins lands before reaching Tombee on its way to Lands End. These all were sand roads with wooden causeways over tidal drains and marshes. They connected the plantations to one another and to the institutions which serviced white society — the churches and the general stores, the Agricultural Society lodge and the muster house, the village of St. Helenaville with its wharf, summer mansions, parsonage, and small boarding schools.

There were no farms on St. Helena worked by free labor, and no cotton that was not produced by slaves. Many plantations bore the names of their owners but not necessarily their current owners. Some plantation names suggested a location or physical feature — Riverside, Comer Farm, Pine Grove, Mulberry Hill. Every name had a history and a reputation, in equity court as well as in public opinion. A name signified a house and a lineage, a collection of assets and the means of producing more wealth, a credit rating and an appraised value. Once a name became attached to a tract of land, it took more than a change in ownership to pry them apart.

What will the land produce? How much to the acre? This is what people who looked to the land for a living wanted to know. Utility mattered most. There was no part of the land — or water — that did not make some contribution to the plantation economy. The sea and tidal streams provided fish and shellfish at all seasons. The barrier islands contributed deer and ducks to the master's larder and wood for a great variety of uses: for heating and cooking; for Negro houses, outbuildings, and fences; for wagon parts, tool handles, and crude furniture. From the marshes came manure for the cotton fields without which a different agriculture would have evolved.

The plantation grounds produced the money crop and most of the food. But the pattern of land use was not static; the land was put to many different uses over time. Imagine visiting the same plantation at 15- to 25-year intervals through the first half of the nineteenth century. What would we see?

In 1795 a St. Helena planter was sowing the new long-staple cotton in an old indigo patch where root crops had been planted after the market for indigo collapsed. Young woods had grown up on fields which were cultivated 20 years before. The human settlement was compact and centralized on a piece of high ground toward the interior of the plantation. The planter's family lived in an old, plain, low house, a sprawling assemblage of rooms added on the basic dwelling over the years. A porchless front facade looked out on an irregular row of Negro houses, stables, and provisions grounds, including a piece set aside for a house garden. A road ran from the front door of the house half the distance across the plantation to a small boat landing on the creek. Behind the house, resting in a small crowded cemetery, were the remains of the planter's father and mother, his stepmother, several of his father's brothers, and numerous children.

Fifteen years later, fattened by fabulous prices for his cotton, the planter has moved his family into a mansion, or Big House — a house about the size of a large New England or Ohio farmhouse — on the creekside of his plantation. From the front veranda, he could look out over water and marshes to neighboring islands. It was a short walk from the front steps of the house to a new dock and boathouse. Out the back door extended the larger part of the plantation. Nearest to the Big House was a separate kitchen building with a small garden beside it; beyond that lay fields. New Negro cabins and stables sat farther from the planter's new residence than they had from his old one, which was now in ruins, pilfered for firewood. There were more Negro cabins — more Negroes — more cotton, and relatively less land in grain and vegetables. Cotton was selling so well that the planter did not try to grow a surplus of food; if he fell short he could afford to buy what he needed. Cotton occupied all the highest ground and was moving into the lower. The woods that had sprouted over old indigo fields were cut to make room for cotton.

A visitor to the plantation in 1830 could not tell immediately that prices for Sea Island cotton had been depressed for a decade. Effects of the large profits made before 1819 were still visible from the dock. Where a flood tide used to creep freely up a gentle incline toward the Big House, leaving lines of detritus in the yard to mark its advances, the tide was frustrated now by a levee that gave to the landscaped yard behind it the appearance of added elevation. The planter had set out shade trees and fruit trees. His wife had planted a flower garden and had succeeded in establishing crested irises and May apples at the edge of the salt marsh. A cluster of outbuildings seems to have risen out of the ground since 1810 — a dairy, a smokehouse, a fowl-house with a coop for exotic birds. In the fields, cotton was firmly established in the low ground as well as the high, though neither area was planted to capacity. More land was in corn and potatoes because it cost more to buy food relative to the income from cotton. One sign of tight economic times was the dilapidation of the Negro cabins, now shielded by bushes and trees from sight of the Big House.

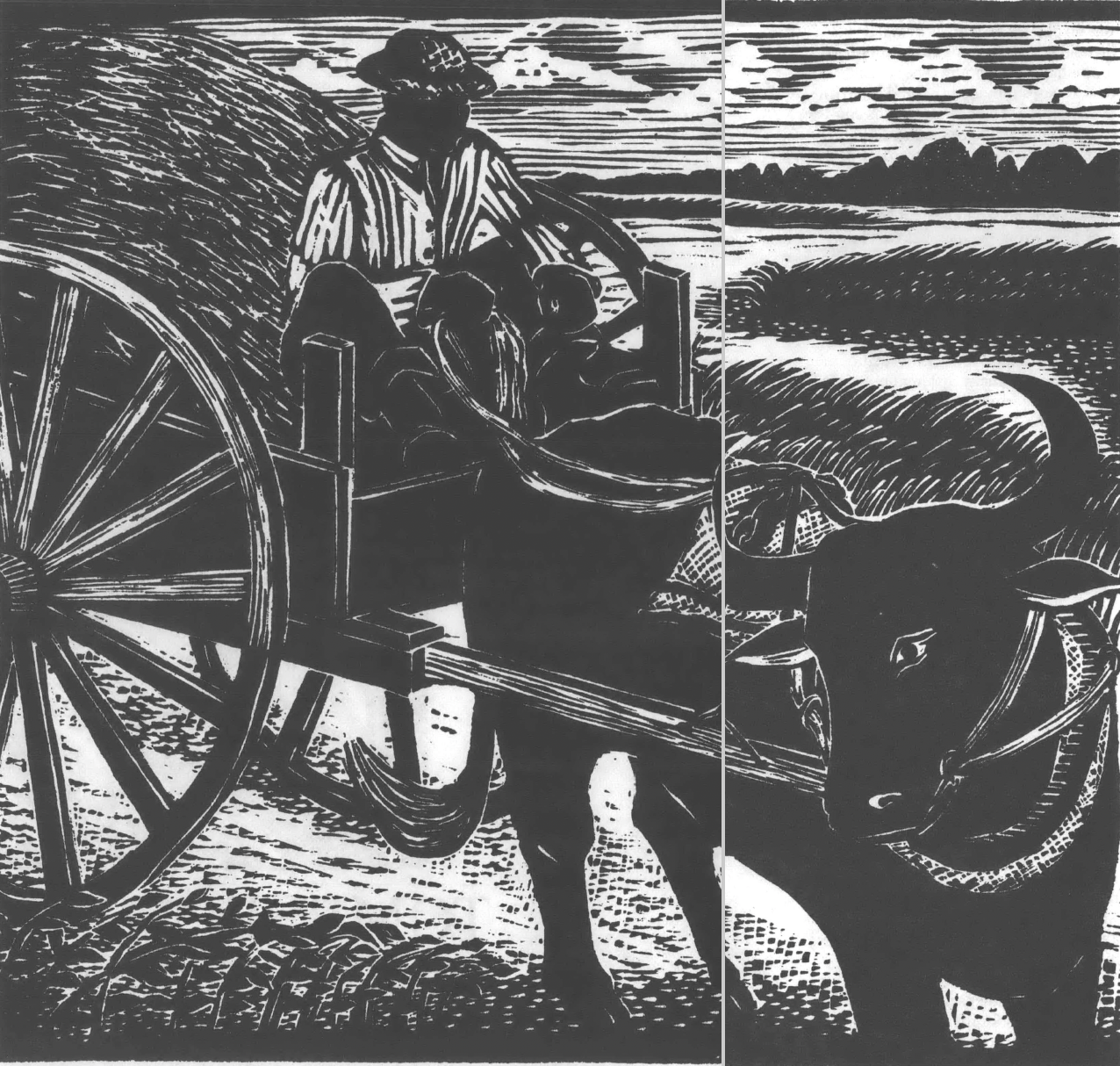

Between 1830 and 1845 the outward appearance of the Sea Island plantation deteriorated slowly. Cotton prices stayed low and the planter hesitated to make capital improvements. Old fences rotted, the Negro houses were mildewed and worm-eaten, and even the Big House had lost its luster. The roof leaked and the exterior stairs needed patching. On the remains of an old generation of outbuildings, new, frugal structures were rising. Crop acreage and the ratio of cotton to com, peas, and potatoes was about what it had been in 1830, but distribution of the crops had changed. Cotton now filled the lowest arable land, thanks to the recent introduction of oxen to haul manure to the damp ground. More corn was planted through the cotton rows, and in the cornfields the rows were longer, narrower, and higher — a sign that the plow had come back in favor. In cotton, however, the plow was still used sparingly and did not challenge the raised-bed system worked entirely with hoes. Orchards were numerous but run down. Pastures were kept up and fine horses prospered. But stock raised for the table, left to forage on their own most of the year, looked thin and poor.

Land use changed conspicuously between 1845 and 1860. Pastures and livestock declined, cotton spilled over onto acres previously planted in grains and vegetables, and more land than ever was in production. The impetus for change was higher cotton prices. Once again, it was more profitable to grow cotton to the doorsteps of the Negro cabins than to set aside land for food crops. "Now plantations are cotton fields rearing a crop for foreign markets and little more," lamented Beaufort's William Grayson at the close of the era. The effect of raising one great money crop, he wrote, was "to starve everything else." Fruit orchards had "almost disappeared. Oranges are rare, pomegranates formerly seen everywhere are seldom met with, figs are scarce and small. Few planters have a good peach or strawberry. . . ." Even the fish and game had mysteriously fallen off.

Grayson was angry that Sea Island commerce — the brokering, freighting, insuring, and financing of cotton — made large profits for middlemen in New York and Liverpool. A good part of the profits that returned to the Sea Islands was subsequently trifled away at watering holes in the North, instead of being spent at home. It was objectionable for planters to purchase their pianos and pineapples from Northern merchants, and unforgivable for them to buy cider pressed in Vermont, butter churned in New York, corn grown in Pennsylvania, and hogs raised in Tennessee, any of which could be produced at home. Even oysters from the North found a market in Charleston, though the salt waters of South Carolina teemed with oysters.

We might view the intensification of cotton planting in a different light than Grayson. Where he saw change, we might remark on the persistence of Sea Island cotton over a period of 80 years — far longer than the age of cotton in such Deep South states as Alabama or Mississippi. Grayson stressed the departure from traditions of mixed farming and conservation of the resources of land and water. We might point to the plantation's capacity to retain its economic function and social character from decade to decade.

To Grayson, taking refuge in the upcountry after Beaufort was abandoned in 1861, the question of the planters' devotion to cotton was a question of life and death, settled on the side of death. Moreover, it had been settled at least a generation before when, in 1841, at the depth of the agricultural depression and with no reason to hope for higher prices, planters began stepping up production of Sea Island cotton. Twenty years of agitation for crop diversification by the agricultural press and the state Agricultural Society went largely ignored. Planters might set aside a sandy hill for grapes or import a bull to improve their milk herds, but they never considered giving up cotton. There were numerous practical difficulties, of course, in switching over from an established staple crop to a new one, not the least of which was marketing. Then, too, memory of old fortunes built by cotton in one or two wildly prosperous years made men reluctant to try something else. They may not have been growing richer with cotton, but it appears that at no time were Sea Island planters faced with out-of-pocket cash losses. They stuck with what they knew because it had been good to them or to their fathers before them, it was not bankrupting them, and it held out the dream of immense wealth quickly earned. Until that day they could live comfortably, if fretfully, off the fat of old harvests.

Then commenced a new era of high prices for cotton, in the 1850s, which shored up their attachment to the old staple, if indeed it had ever eroded. Had they turned to sugar beets or millet or hemp or any of the other foods and fibers proposed as substitutes for cotton — had history gone in the direction Grayson would have preferred — Sea Island planters still would have been susceptible to secession hysteria, so long as they worked their crops with slaves. But if their major crop had not been cotton they might have been less prone to the catastrophic illusion of their importance to the rest of the South and to England. With less cotton they would have made a less inviting target. There is no doubt that the great cotton crop of 1861, some of it already ginned and baled, and the balance of it waiting to be picked, encouraged Union military planners to invade Port Royal, of all likely places on the South Atlantic coast.

Sea Island cotton in 1860 had brought upwards of 60 cents a pound for medium fine varieties. Planters were expecting even better returns in 1861. In October the Charleston Mercury reported that bales of the new cotton, received at the market but kept in port by the Union naval blockade, compared "most favorably with the growth of former years, in bright appearance, strength, and length of staple." Following the invasion of Port Royal in November, the crop of St. Helena Parish was confiscated and shipped to New York, where it was ginned and sold, bringing a total of $675,000 to the United States Treasury. Thus the proceeds from one of the largest and finest Sea Island crops ever produced — including, from St. Helena Island, 20 bales from Thomas B. Chaplin, 45 bales from T.G. White, 85 bales from Dr. William J. Jenkins, and 110 bales from J.J. Pope — were used to finance the war against the planters.

This second excerpt contains entries from Thomas B. Chaplin's Journal for six days in February 1849. The first five days are taken up with agricultural items typical of Chaplin's concerns —preparing cotton for market, keeping up plantation resources, worrying about the weather, overseeing the work of the slaves. Events of the sixth day are unique in the Journal, both in the brutality of the subject and the extent of Chaplin's narration. On the morning of February 19, 1849, Chaplin joined 11 other St. Helena planters — about one-fifth of the adult white males on the Island — at an inquest to decide whether one of their neighbors and peers should be brought to trial for killing a slave. Chaplin's revulsion over the crime and dissent from the majority opinion show him at his most merciful. In years to come, his attitudes harden and he becomes more conventional and less humane in his outlook.

Feb. 14th. Wednesday. Aimar came to work at the smokehouse, Sancho working with him. The cattle broke out of the pen last night & eat down nearly everything in the garden — onion, cabbage plants & turnips. Tis damned disheartening. Packed the 9 bale of cotton. 326 lbs.

Feb. 15th. Thursday. 5 gins. The Capt. came round & paid Mother some money — Daphne's wages. Aimar finished the brickwork to the smokehouse, tried it, & it does admirably, the cost, $9.00. I did not expect to pay more than five dollars. Let Aunt Betsy have some asparagus roots. I feel quite unwell today, very much like fever.

Feb. 16th. Was greatly surprised on looking out of the window this morning to see the ground almost covered with snow. It must have snowed gradually all night, but the ground was not in a state for it to lie, & was only covered in spots. The tops of the houses were covered about 2 inches thick. Some snow fell after I got up, but stopped about 11 o'clock a.m. & about 2 p.m. there was hardly a flake to be seen. This is the first snow I have seen since I have lived on the Island. There was a snowstorm I recollect here when I was a boy. E. Capers came to see me yesterday evening & stayed all night.

Finished weatherboarding the smokehouse. Finished ginning all the white cotton, will have 10 packed bags, will not pack the last bale before Monday. The weather cleared off about 11 o'clock & no one would suppose there had been snow on the ground in the morning.

Feb. 17th. Saturday. Clear and cold. Run out, staked & burnt off the root patch, 4 acres. Isaac & Anthony with me. Put Sancho with Summer carting. 4 hands getting poles for the fence. Women cleaning cotton ginned yesterday.

Hear that Edw. Chaplin intends to sell all of his Negroes and go regularly into merchandising. One of his fellows came here today to ask me to buy him, fellow Cuff. That was out of the question for me to do, to sell one year & buy the next would be fine speculation on my part.

Feb. 18th. Sunday. I had to go out last night and have fire put out that got away from where I had burnt yesterday. It burned some of Cousin Betsy's fence at the Grove, only a few panels. The fire went over Jn. L. Chaplin's pasture & passed by his fence, but the water in the ditches prevented the fence from burning.

Feb. 19th. Monday. I received a summons while at breakfast, to go over to J. H. Sandiford's at 10 o'clock a.m. this day and sit on a jury of inquest on the body of Roger, a Negro man belonging to Sandiford. Accordingly I went. About 12 m. there were 12 of us together (the number required to form a jury), viz. — Dr. Scott, foreman, J.J. Pope, J.E.L. Fripp, W.O.P. Fripp, Dr. M.M. Sams, Henry Fripp, Dr. Jenkins, Jn. McTureous, Henry McTureous, P.W. Perry, W. Perry & myself. We were sworn by J.D. Pope, magistrate, and proceeded to examine the body. We found it in an outhouse used as a corn house, and meat house (for there were both in the house). Such a shocking sight never before met my eyes. There was the poor Negro, who all his life had been a complete cripple, being hardly able to walk & used his knees more than his feet, in the most shocking situation, but stiff dead. He was placed in this situation by his master, to punish him, as he says, for impertinence. And what this punishment — this poor cripple was sent by his master (as Sandiford's evidence goes) on Saturday the 17th inst., before daylight (cold & bitter weather, as everyone knows, though Sandiford says, "It was not very cold"), in a paddling boat down the river to get oysters, and ordering him to return before high water, & cut a bundle of marsh. The poor fellow did not return before ebb tide, but he brought 7 baskets of oysters & a small bundle of marsh (more than the primest of my fellows would have done. Anthony never brought me more than 3 baskets of oysters & took the whole day). His master asked him why he did not return sooner & cut more marsh. He said that the wind was too high. His master said he would whip him for it, & set to work with a cowhide to do the same. The fellow hollered & when told to stop, said he would not, as long as he was being whipped, for which impertinence he received 30 cuts. He went to the kitchen and was talking to another Negro when Sandiford slipped up & overheard this confab, heard Roger, as he says, say, that if he had sound limbs, he would not take a flogging from any white man, but would shoot them down, and turn his back on them (another witness, the Negro that Roger was talking to, says that Roger did not say this, but "that he would turn his back on them if they shot him down," which I think is much the most probable of the two speeches). Sandiford then had him confined, or I should say, murdered, in the manner I will describe. Even if the fellow had made the speech that Sandiford said he did, and even worse, it by no means warranted the punishment he received. The fellow was a cripple, & could not escape from a light confinement, besides, I don't think he was ever known to use a gun, or even know how to use one, so there was little apprehension of his putting his threat (if it can be called one) into execution. For these crimes, this man, this demon in human shape, this pretended Christian, member of the Baptist Church, had this poor cripple Negro placed in an open outhouse, the wind blowing through a hundred cracks, his clothes wet to the waist, without a single blanket & in freezing weather, with his back against a partition, shackles on his wrists, & chained to a bolt in the floor and a chain around his neck, the chain passing through the partition behind him, & fastened on the other side — in this position the poor wretch was left for the night, a position that none but the "most bloodthirsty tyrant" could have placed a human being. My heart chills at the idea, and my blood boils at the base tyranny— The wretch returned to his victim about daylight the next morning & found him, as anyone might expect, dead, choked, strangled, frozen to death, murdered. The verdict of the jury was, that Roger came to his death by choking by a chain put around his neck by his master — having slipped from the position in which he was placed. The verdict should have been that Roger came to his death by inhumane treatment to him by his master — by placing him, in very cold weather, in a cold house, with a chain about his neck & fastened to the wall, & otherways chained so that he could in no way assist himself should he slip from the position in which he was placed & must consequently choke to death without immediate assistance. Even should he escape being frozen to death, which we believe would have been the case from the fact of his clothes being wet & the severity of the weather, my individual verdict would be deliberately but unpremeditatedly murdered by his master James H. Sandiford.

NOTE

1. Observers could not agree what caused the depression. Some linked the abrupt decline to the passage of Sir Robert Peel's Act, of 1819, by which Parliament set a date for the return to cash payments in overseas trade. It is not clear, however, if in the ensuing panic the demand for precious metals contracted the financial resources of England's trading partners, or if it was "the contraction of enterprise, confidence, and credits" which led to the resumption of cash payments. Many observers believed the price of Sea Island cotton had been inflated for a generation and was settling now into a more realistic relation to the cost of food crops and other commodities.

Leading Sea Island growers chided their colleagues for passively accepting the depression. Whitemarsh B. Seabrook and William Elliott criticized planters for planting too much cotton; for turning management of the sensitive crop over to hirelings, while they spent the growing season away from home; for neglecting the scientific side of their vocation to pursue pleasure at spas and racetracks; for forfeiting the power that could have come from cooperating with one another. The old Sea Island name was not enough to guarantee a good price. Buyers reacted to the actual condition of the crop. Planters had grown sloppy in cleaning and packing their cotton, mixing several grades in the same lot and allowing the ginned staple to fell to the floor of the gin house where it picked up trash that rode in it to the bale. Spinners at the mills "would frequently find, in addition to a large supply of leaves and crushed seeds, potato skins, parts of old garments, and occasionally a jack-knife." Out of this situation arose a movement for reform and for the diffusion of agricultural knowledge. Prices were not much affected by the planters' reforms, however, though a clean and lightly handled crop would always fetch a premium.

Tags

Theodore Rosengarten

Theodore Rosengarten is a longtime friend of the Institute for Southern Studies and the author of All God's Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw. (1984)