This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 1, "The Jesse Helms Machine." Find more from that issue here.

This article is part of a series by the Institute for Southern Studies’ Campaign Finance Project, produced in conjunction with the N.C. Independent with research partially funded by the Project for Investigative Reporting on Money in Politics and the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation. It was written by Bob Hall with the assistance of project director Marcie Pachino. Chief researchers were Ruth Ziegler and Chris Nichols.

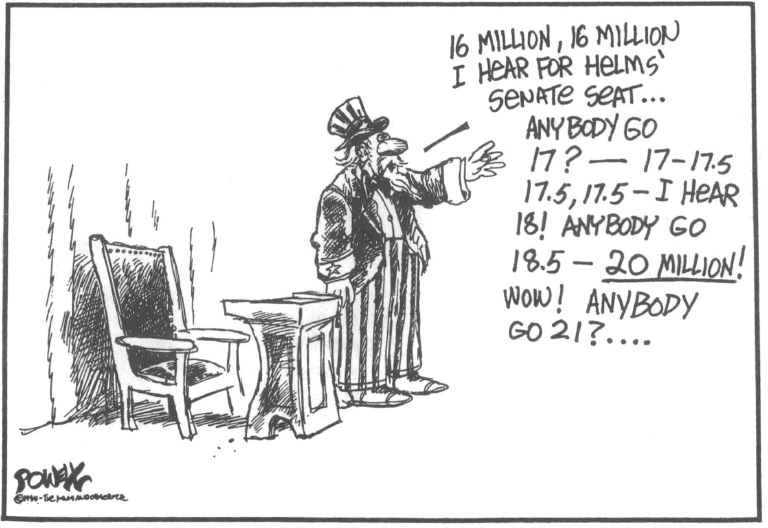

North Carolina’s bitterly contested 1984 Senate race between Republican Jesse Helms and Democratic Governor Jim Hunt will go down in history as one of the meanest, ugliest, and most divisive campaigns ever. For months, North Carolinians could not read a newspaper, watch television, or open their mail without being bombarded by political rhetoric, mud-slinging, and pleas for money.

In the end, the money made the difference. It transformed traditional backslapping politics into a war of 30-second television commercials. And it elevated name-calling from an occasional verbal punch below the belt to a shrill pitch broadcast with such frequency that voters were either dulled into submission or provoked into action.

The dollars spent in the race literally boggle the mind. Helms raised $15.9 million, or about $14 for each of the 1,156,768 votes he ultimately received. Hunt took in $9.7 million, nine dollars apiece for his 1,070,488 votes. The $25.6 million total* sets an all-time high for a statewide political contest. In its closest rival — California’s 1982 Senate race — 17 candidates slugged it out through three elections (primary, run-off, and general election) for the support of four times as many voters as live in North Carolina. They still only spent $22 million.

With only token opposition in their respective primaries, Helms and Hunt knew they faced a one-on-one confrontation from the beginning. Each side started building its financial war chest two years before the election, largely through direct-mail appeals, and by the spring of 1983 Helms was already spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on his now-famous “negative” advertising. Consistent throughout the campaign, the ads attacked Hunt’s personal credibility and exposed his “liberalism” by characterizing him as (1) “wishy-washy” and inconsistent, especially on issues like school prayer; and (2) closely tied to “union bosses,” “homosexuals and militant feminists,” and “out-of-state radical leaders” like Edward Kennedy and Jesse Jackson. By contrast, Hunt’s television ads lacked a central theme and didn’t begin until a year after Helms’s; hard-hitting attacks on the senator’s preoccupation with “right-wing extremists” worldwide gave way to a mish-mash of commercials defending Hunt’s credibility, reflecting the overall cautious approach of his campaign.

In September 1984, the Charlotte Observer reported that Helms was spending 45 percent of his millions on political advertising and another 27 percent on fundraising mailings. By election day, the Raleigh News & Observer estimated that Helms had paid for 15,000 television ads, while Hunt had aired 7,000 — but the final numbers may be three times these figures. In a 12-week period in early 1983, Helms blitzed the state with 12,000 anti-Hunt ads in 150 small-town newspapers and 80 radio stations. “Independent” groups not directly tied to the candidates paid for hundreds of additional commercials; in June 1984, for example, the Fund for a Conservative Majority kicked off a $1 million pro- Helms campaign by airing a 30-second spot 99 times in 10 days in the state’s five major TV markets.

One more statistic underscores the power of this costly barrage of television advertising: the majority of adults in 62 of North Carolina’s 100 counties never finished high school. Many are functionally illiterate; most get their news wholly from the airwaves. Is it any wonder that the image dominating the TV screen decided the outcome of the Senate race?

Still, the margin of victory was relatively slim — only 86,000 votes out of 2,200,000 cast — and other factors, beyond the millions of dollars, surely influenced the final results on November 6. For example:

● The coat-tail effect of Reagan’s landslide (62 percent of the state’s vote) imitated Nixon’s 69 percent victory over McGovern in 1972 when Helms first won his Senate seat.

● A united state Republican party, helped by a clean-cut gubernatorial candidate who promised a repeal of the food sales tax, produced more than 800,000 straight party votes, even for unknowns like the Republican candidate for agricultural commissioner.

● Well-publicized voter registration drives by Jesse Jackson and the Moral Majority symbolized aggressive work at the grass roots — and deep-seated racial polarization, which Helms used to his advantage: “Jim Hunt needs an enormous black vote to put him across, but if enough of our people go to the polls it will be OK,” he told reporters. New white voters added between November 1982 and ’84 outnumbered new black voters 420,000 to 170,000.

● Hunt held his own in the TV debates, and in campaign speeches he effectively contrasted his record of delivering more jobs, better schools, and good roads with Helms’s fascination with fringe issues. But a poorly planned media campaign allowed Helms to take control of the race and left Hunt with a $700,000-plus surplus.

● Hard-fought Democratic primaries burned out campaign workers, fractured the party, and left many voters “without a candidate.” Eddie Knox, the choice of most liberal and black groups in the gubernatorial run-off, wound up endorsing Reagan and denouncing Hunt for not helping him.

Such fortuitous circumstances certainly played into the hands of Jesse Helms. But for a comical, knee-jerk reactionary to defeat the darling of Southern Democrats took more than luck and pluck. It required considerable foresight, planning, and organization, proving the aptness of Elizabeth Drew’s analysis in the July 20, 1981, New Yorker. “He [Helms] is not just another senator, he is a force — and he represents a new political phenomenon. He and his extensive network of aides and allies have figured out how to tap some very old strains in American politics through a cool use of some of the most modem, sophisticated and original political techniques.”

At the heart of this new “phenomenon” and of Helms’s success is a well-oiled money-raising machine that gives him and his associates the power to overwhelm rational political discourse with a hot-tempered morality play which they can manipulate for mass appeal — and for more money. Or as Helms himself explained it three weeks after his victory: “We raised the money to break through the journalism curtain, and we took the story directly to the people.”

THE SELLING STORY

The “story” Jesse Helms broadcast over the airwaves and through his fundraising mailings boils down to a fantasy — one that many people (especially white males) share, because it connects them to a glorious world where “a man’s home is his castle” and “my country ’tis of Thee.” Jim Lucier, a top Helms aide, describes the secret of his boss’s appeal:

“The problem in our country is there is a tremendous gap between the people as a whole and the leadership groups that run the country — not just the media but also politicians, corporate executives, financial officers of major banks, and so forth. They have been trained in an intellectual tradition that is not only at variance with the way the ordinary person thinks but is contradictory to it. Helms is not right-wing. He’s not even political. The issues he’s involved in are pre-political.

“What I mean is,” Lucier continues, “the intellectual training of those groups I referred to is highly rationalistic… The principles that we’re espousing are ones that have been around for thousands of years: The family as the basis of social organization. Faith in the transcendent world — that God is the creator of this world that we live in, and there is a higher meaning than materialism. Property as a fundamental human right — the idea that your home is your castle and the government can’t come in and take it away from you…

“Another fundamental principle is loyalty to the country that you live in. Feelings that have been long suppressed,” Lucier concludes, “are coming back to the surface, because politicians have distorted society — whether it’s busing that breaks up the family or deficit financing that redistributes income. A society can absorb a little at first, but eventually these things distort the basic structure so much that it flies apart.”

A lesser demagogue might fail to capitalize on these insights about the selfish underside of the American psyche. But for a dozen years the Helms organization has raised, and spent, millions of dollars by repeating these prerational themes over and over in fundraising letters to a national constituency frightened by the liberal assault on God, family, property, and American pride.

“Helms can go out and pick up seven or eight million dollars and doesn’t need the leadership groups,” says Lucier. “Direct mail short-circuits the media and goes right into people’s mailboxes.” Or as Richard Viguerie, godfather of right-wing fundraisers, says, “Without direct mail, there would be no effective counterforce to liberalism, and certainly there would be no New Right.”

By carefully testing the response each appeal generates from different types of people (i.e., computerized lists), Helms’s direct-mail fundraisers have learned which “story” works most effectively — and which new slant to take in their next mailing. The huge sums raised every month through this technique meant Helms’s strategists could afford to use a torrent of 30-second commercials to implement a campaign plan based on the same basic principles as their direct-mail program:

(1) make direct contact with people, bypassing media interpreters, party officials, and other intermediaries;

(2) keep on the offensive, start early, and constantly throw in new issues and charges which earn your supporters’ continued attention (and dollars) and keep your opponent off balance;

(3) polarize the battle into an ideological crusade between the demonic forces of liberalism and the senator who is not afraid to stand up for what’s right; (4) personalize and tailor the message to targeted audiences, and continually test and refine it to improve its effectiveness in generating the desired response.

Both the ads and the direct-mail appeals are coordinated by the overlapping personnel at the National Congressional Club, Helms for Senate Committee, and Jefferson Marketing, Inc. (JMI). Hunt scored points by alleging that the movement of money and people between these groups illegally subsidized Helms’s campaign, but the courts have yet to rule on the issue. The extent of the profits JMI earns from work done for Helms, which its officers manage in the first place, also remains unanswered.

Meanwhile, the creative minds behind the Helms morality play kept cranking out a story line that capitalized on people’s anxieties, made effective use of scapegoats, and polarized the campaign into a holy crusade against the enemies of God and America. The most extreme versions went directly to targeted markets of potential supporters.

For example, a fundraising letter sent out by JMI to a list of Southerners for Reagan said $217,855 was desperately needed to recruit 250,000 new voters in North Carolina to offset the voter registration efforts of “radical black civil rights leader Jesse Jackson.” The letter called Jackson a “carpetbagger” and condemned “out-of-state northern liberals who have come south to destroy our heritage and way of life. I know you understand what I’m talking about,” explained the letter’s signer, the great-great nephew of Robert E. Lee.

A 30-second ad aired in urban television markets during a Monday night football game featured Dallas Cowboy coach Tom Landry: “We can count on Senator Helms to fight the tough ones. America needs its champions now more than ever.” Ads, flyers, and even a comic book appearing in the rural, eastern part of the state blasted Hunt for taking money from “radical blacks,” “union bosses,” and “homosexuals out of the closet.”

Singer Pat Boone signed an appeal to a list of fundamentalists asking for $42,500 to counter “the un-Godly lies the liberals are spreading about Jesse.” Boone praised Helms’s efforts to ban abortion, stop forced busing, and strengthen U.S. defenses against the Soviets. And he ended with a postscript: “You and I need Jesse in Washington. America needs him. God needs him.”

Another letter sent nationally asked for money to organize “Christians” inside North Carolina because “dangerous liberals like Jesse Jackson are roaming the back streets” to register Mondale- Hunt supporters.

Virtually every letter Helms signed labeled the campaign a contest between the “patriotic,” the “dedicated,” and the “religious” against “ruthless union bosses, abortionists, pornographers, homosexuals, and biased news commentators [who] are out for my political hide.”

The statewide television commercials paid for by these letters portrayed the contrast in less strident terms. Because they were seen by North Carolina voters, rather than a national constituency of true believers, the ads focused more specifically on Hunt, playing on his reputation as an ambitious politician who talked out of both sides of his mouth on sensitive issues, unlike the unequivocal Helms. Once Mondale received the nomination, the ads presented a simple choice between flag-waving Republicans led by Ronald Reagan and high-taxing liberals serving the “special interests.” Or, as stated in its 10-second version which a viewer might see six times an evening: “President Reagan and Senator Helms oppose tax increases. Walter Mondale and Jim Hunt have promised to raise taxes.”

Even though Hunt rebuked Mondale’s tax plan, Helms’s ads showed him saying he supported Fritz Mondale for president and raising his hand in favor of a federal tax hike at a national governors’ conference. And even though Hunt is far from a liberal on domestic and foreign policy issues, nearly every anti-tax ad concluded with the announcer intoning, “Jim Hunt, a Mondale liberal.” This phrase came as the subtle answer to the tag line which closed the first wave of ads on the “flip-flopping” Hunt: “Where do you stand, Jim?” The answer: “Jim Hunt, a Mondale liberal.”

Claude Allen, press aide for Helms, called this type of advertising “political education.” After his victory, the senator praised the discerning wisdom of North Carolina voters: “They went to the polls and made clear they understood.” Independent observers disagree. “Liberal is a dirty word in North Carolina,” said Richard Slatta of N.C. State University. “People didn’t vote on the issues, they voted on the label of liberalism.”

Ferrell Guillory, associate editor of the Raleigh News & Observer, also criticized the Helms letters and ads for imposing “an artificial liberal-versus-conservative dichotomy on the Senate race and on the political system as a whole.” To Claude Allen, this dichotomy properly described the essence of the entire campaign. “In a senate race, voters want to elect a person with an ideology,” he said. “Since a senator votes on so many issues, we need a person who puts forth a philosophy. Hunt was running a governor’s campaign, not a senate race, [with his] talk about education, social security, etc.”

By getting its ads out early, often, and with forceful images, the Helms machine made the campaign the ideological fight it knew it could win. It was an expensive experiment in “political education.” But Helms’s money meant he could make it work.

WHO GAVE THE MONEY

Independent polls before and after the election provide reams of data on who voted for which candidate. Helms’s strongest support came from white males, from the western counties of the state which have a Republican heritage, and from voters who didn’t finish high school. On the other hand, Hunt’s huge lead among black voters (20 percent of the state’s electorate) helped him carry most of the larger urban areas and the eastern counties and a narrow majority of all women voters.

Far less is generally known about who gave Helms (or Hunt) the money to get his “story directly to the people.”

Post-Watergate reforms limit the amount of money an individual can contribute directly to a candidate to $2,000 — $1,000 for the primary and another $1,000 for the general election. “The fat cats are dead,” proclaimed campaign finance expert Herbert Alexander in 1976. “The real effect of the Watergate campaign reforms has been to vastly increase the power of one man — Richard Viguerie. Once you have limited the amount of money the big contributors can kick in, it becomes necessary to reach thousands of small contributors. And Viguerie, more than anyone else, is the proven master of this.”

If interviewed today, Alexander might add Jesse Helms’s in-house direct-mail experts to the list, and perhaps Jim Hunt’s consultant, Roger Craver of Craver & Mathews. Alexander might also retract his dismissal of the role of “fat cats,” as we’ll see shortly. But his observation about the strategic importance of a broad-based fundraising effort is still accurate.

Nearly 65 percent of Helms’s money, or $10 million, came from individuals who contributed less than $200, mostly in response to his appeal letters. By contrast, Hunt received half as much — $5.2 million — from donors of less than $200, and a large share of this amount came from dozens of fundraising events held in and out of the state, or collected by his army of 2,300 county leaders.

The typical direct-mail giver, says Elizabeth Drew in Politics and Money, is over 50, lives in a suburb or rural area, often alone, feels frustrated by world affairs, and lacks an outlet for his or her political beliefs. According to former Senator Thomas J. McIntyre’s study, The Fear Brokers, “the encapsulated evangelical, devoid as he or she is of a cohesive political philosophy or party allegiance, is particularly vulnerable to the highly personal single-issue politics practiced so assiduously by the New Right.”

Helms’s letters invoking paranoia perfectly target this direct-mail responsive market. And his frequent use of personalized letters to the members of single-issue groups — gun clubs, Christian academies, conservative business leaders, anti-abortion groups, etc. — enhances his return rate of contributions. But these mailings are costly, and it takes donors of over $200 to provide the flood of surplus cash needed to pay for new mailings while also underwriting an expensive media campaign.

The identities of Helms’s smallest contributors will never be publicly known (the Federal Election Commission requires candidates to report only the names and addresses of those who give more than $200). But a glance through the print-out of Helms’s largest financial supporters reads like a roster of the most notable figures in twentieth-century conservatism.

After hundreds of hours of research (see page 24), the Institute for Southern Studies’s Campaign Finance Project identified the economic interests of 93 percent of the 1,800 largest individual donors to the Hunt and Helms campaigns, as of June 30, 1984. We also questioned these contributors about why they gave $1,000 or more to the candidates of their choice.

The results of our study show a dramatic difference between the financial constituencies of Hunt and Helms — a polarity that even exceeds the political gulf separating the two men.

Nearly two-thirds — 64 percent — of Hunt’s largest supporters are white-collar professionals in real estate, law, finance, trade, communications, and service industries. Their businesses prosper under government-stimulated economic growth, when more cash flows through the pockets of an expanding middle class. They are moderates and liberals, disproportionately Jewish, and often pro-labor.

Instead of championing a pure free-enterprise system as the source of efficient production and moral discipline, Hunt’s donors are the prime beneficiaries of a managed economy which true right-wingers abhor. Writes historian Richard Hofctadter: “The modem economy, based on advertising, lavish consumption, installment buying, safeguards to social security, relief to the indigent, government fiscal manipulation, and unbalanced budgets, seems reckless and immoral — even when it happens to work — [to] conservatism.”

Most Hunt contributors interviewed said they were less attracted by the governor’s eclectic positions on issues (pro-“right-to-work” laws, pro-ERA, anti-Freeze, anti-labor law reform) than they were adamantly opposed to Jesse Helms. Two of the senator’s staunchest, richest enemies — pro-Israel groups and labor unions — gave Hunt 62 percent of the money he received from political action committees (PACs). (Despite the national attention on PACs, they provided less than 10 percent of the money raised by either Helms or Hunt — see chart below).

In sharp contrast to Hunt’s supporters, 52 percent of Helms’s biggest money givers are retired or active manufacturers (especially in low-wage industries), agribusiness operators (from Texas cattle ranchers to California fmit growers), independent oil producers, building contractors, printers, and publishers. Rather than being in the middle between producer and consumer, owner and worker, most of Helms’s biggest givers are risk-taking entrepreneurs, owners of medium-sized, often family-dominated businesses, producers of hard goods rather than services.

These donors are ideologically opposed to unions, welfare, and government regulation. Helms won their favor by voting correctly on labor law reform, corporate tax breaks, environmental re- strictions, crop price supports, and the windfall oil tax. He got a rating of 98 out of 100 from the Independent Petroleum Association and a 97 from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Impressed by more than a voting record, however, most of these contributors say they sent money to Helms because they cherish his ideology, or as Hugh Palmer of Montana’s Palmer Oil & Gas said, “We need a ... lot more Jesse Helmses. His political philosophy balances with mine.”

A large proportion of the big Helms supporters we interviewed said they were over 65 and had given to conservative causes for decades. As a group, they fit the classic profile of the Old Rightist: passionate defenders of “free enterprise” against the triple threats of international communism, organized labor, and government interference with the prerogatives of private property. Typical responses to our question of why they support Helms reflect an ultraconservative love affair with economic individualism that breeds anti-communism and racism:

● “To retain the free enterprise system.”

● “To maintain my freedom; to halt the headlong rush of Federal Government toward state socialism.”

● “To halt the illegal immigration of Hispanics, Mexicans.”

● To try to prevent my country from going completely communistic.”

An exhaustive search through the files of Group Research, a Washington-based organization that monitors the Right, turned up links between scores of Helms’s largest contributors and the network of Old Right groups that flourished in the 1950s and ’60s, in an era of Cold War, labor organizing, and civil rights agitation. The more research we conducted, the more it became evident that the key contributors to Jesse Helms are not the stereotypical New Right activists who belong to single-issue groups devoted to moral or social causes like abortion and school prayer. Instead, they are longstanding financial backers of groups that follow the pattern of the Old Right, as described by Richard Slatta and others: their first allegiance is to “self-centered economic interests,” often magnified by a paranoid or conspiratorial view of the enemies threatening these interests. Consider these examples:

● Roger Milliken, 69, heads the Spartanburg, South Carolina, family owning the world’s largest privately-held textile company, Deering-Milliken; and he typifies many Helms donors from low-wage businesses who have long supported Old Right union-busting groups like the U.S. Industrial Council (Charles Reynolds of Spindale Mills and James Edgar Broyhill of Broyhill Furniture are two more examples). One of several Helms contributors on the 1961 Draft Goldwater Committee, Milliken has given tens of thousands to such Old Right groups as the Christian Anti- Communist Crusade, Manion Forum, and National Right to Work Committee (see descriptions in sidebars). On the day before unrecorded contributions became illegal, he gave Nixon’s campaign $363,122. He now gives thousands to New Right PACs, like NCPAC and Helms’s Congressional Club. His family gave Helms $4,000. Milliken is best known in union circles for flouting the National Labor Relations Board by abruptly closing a mill to block his employees’ pro-union vote.

● Glen O. Young, 90, calls Helms the “greatest statesman of our time” and Martin Luther King, Jr., “that communist rabble-rouser.” He blames “liberals” for the demise of Joe McCarthy, and at the 1973 convention of the Liberty Lobby he circulated a petition demanding that Golda Meir be imprisoned “as was Adolf Eichmann.” An Oklahoma attorney, he gave Helms $2,765 — $765 more than the legal limit. Like dozens of other contributors, he has been an officer, advisor, or donor to a nest of Old Right groups which typically include words like “liberty,” “freedom,” or “Christian” in their names. In his case, these include: the Christian Crusade, John Birch Society, the Freedom School, Committee to Repeal the Great Society, Congress of Freedom, and We, the People.

● Mrs. N.C. Pentecost, of Robert Lee, Texas, was the Christian Crusade’s 1964 Woman of the Year, and she typifies supporters who use loopholes to get a candidate more than the $2,000 limit. Members of her family gave $8,000 directly to the Helms for Senate Committee, but they also gave more than $10,000 to his National Congressional Club. This practice is widespread among both notorious “fat cats” (brewery magnate Joseph Coors and family gave $15,000 to Helms and the Congressional Club, plus an equal amount to other PACs which supported Helms), as well as the less known (Julie Lauer-Leonardi, who once owned part of the Birch Society’s weekly magazine, gave $2,000 to the Helms committee, $2,000 to the Congressional Club, $2,500 to the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, and $1,000 to the Conservative Caucus’ PAC).

● Nelson Bunker Hunt, 58, son of H.L. Hunt and one of the ten richest people in the U.S., heads the list of Texas oil moneymen giving to Helms. He’s given millions to right-wingers ranging from the Birch Society to Moral Majority. And he’s figured out another way to get around the limits on how much he can give a candidate. While his family gave $4,000 to Helms, he also dropped $90,000 into the Helms-related Institute for American Relations. “We’re not as smart as other people, so we need every advantage,” he explains. Another Dallas oilman, Roy Guffey, shares Bunker Hunt’s contempt for the democratic process: “A majority of voters are a bunch of damn thieves.” He gave Helms and the Congressional Club $13,600.

● Racists and anti-Semites on the contributors list are exemplified by J. Evetts Haley, 83, who ran for governor of Texas in 1956 on a platform condemning integration as a Soviet plot to destroy the white race in America (his family gave $6,700); and Bernadine Bailey, 83, of Mattoon, Illinois, who says, “The Jews plan to take over the world. They already own our banks, they run our media. . . . They plan a complete world takeover by the year 2000.” She gave Helms $1,140 because she likes his votes against aid for Israel.

OLD RIGHT TACTICS AND IDEOLOGY

The significance of the dollars that come from people like these is not lost on Jesse Helms: he needs their money to finance his direct-mail enterprise and new efforts like his Fairness in Media campaign against CBS; and they need him as a national spokesman to rally their racist and free-enterprise cause at home and abroad, and to give it a broader base within the New Right. But the mutual interest of Helms and the Old Right has become a matter of money and power today only because the senior senator from North Carolina has a 35-year-long commitment to the tactical approaches and ideological beliefs of right-wing extremism. That’s the deeper meaning of this money.

First, on tactics, the chief method that Helms, like the Old Right, has used to promote any cause is the tearing down of his enemies through racism and guilt by association (especially red-baiting, or in current phraseology, liberal-baiting). Both Helms (age 63) and his top political advisor, Tom Ellis (age 64), got their start in partisan politics in the state’s 1950 Senate race, which Wayne Greenhaw in Elephants in the Cottonfields calls “one of the most knock-down, drag-out campaigns of Southern politics.” In that contest the Ellis-Helms opponent, Frank Porter Graham, lost after a smear campaign that included the distribution of handbills with a doctored photograph of his wife dancing with a black man, repeated allegations about Graham’s communist ties, and newspaper ads denouncing his “race-mixing” practices.

While Helms went to the Senate as the administrative assistant of the winning candidate, Tom Ellis continued in the Old Right tradition — leading a propaganda campaign to undermine the state’s school desegregation plan in the late 1950s; joining the board of the Pioneer Fund, which tried to prove the genetic inferiority of blacks; and becoming a partner in a union-busting law firm in Raleigh. Helms returned to Raleigh in 1953 as chief public relations flak for the N.C. Bankers Association. In 1960, as editorialist for WRAL-TV, he began 12 years of railing against deadbeats, socialized medicine, the UN, “shiftless Negroes,” and the “moral degenerates” led by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Ellis managed Helms’s first Senate campaign in 1972 against a Greeksumamed supporter of George McGovern whom they tagged as soft on communism and not “one of us.” In 1976 Ellis coordinated Reagan’s campaign in the North Carolina primary and was caught distributing handbills accusing Gerald Ford of wanting a black man as his running mate. By 1978 Ellis had founded the Congressional Club and Jefferson Marketing, and the second campaign for Helms raised $8.1 million to spread innuendos about his Democratic challenger’s morality and ties to labor unions.

Today, an insider in the Helms complex of organizations says that Tom Ellis is “the brains behind all the things that we do.” No one who knows the background of the Ellis-Helms team should be surprised at their tactics, including their latest favorite weapon — gaybaiting. For them, it is a proven method of throwing their enemy off-guard, mobilizing their supporters to action, and, as we have seen, reaping millions from a network of far-right enthusiasts.

Beyond tactics, the significance of the Old Right’s money involves ideology. Unlike Jerry Falwell and many New Right leaders who think first of the moral decay of America at the hands of liberals, Helms (and Ellis) share the Old Right’s primary allegiance to free enterprise and the sanctity of private property. According to Helms, “The right to own, manage, and secure property is not merely the most sacred of ‘human rights’ — it is the very basis of civilization.”

Helms’s missionary zeal in spreading this vision of civilization worldwide helps explains his preoccupation with U.S. foreign policy. Through his own network of foundations and research centers and as chair of the Western Hemisphere subcommittee of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he has made himself chief ally and spokesman for extremist leaders in Latin America and elsewhere. He frequently praises military dictators on the Senate floor; on the campaign trail he called Roberto d’Aubuisson, an alleged leader of El Salvador’s death squads, “a deeply religious man” and compared him to “the free-enterprise folk in the city of Charlotte.”

Helms has even criticized the New Right conservatives in Congress who recently condemned South Africa’s policy of apartheid, because, he says, “it is better to reason with anti-communist governments than to overthrow them.” The typical Old Right linkage between black self-determination and communist rule runs throughout Helms’s TV editorials of the ’60s, his virulent opposition to civil rights legislation, and his one-man campaign against a holiday honoring Martin Luther King, who he says “welcomed collaboration with Communists.”

As chairman of the Agriculture Committee, Helms’s anti-government ideology runs counter to farm support programs; so while he pokes holes in the food stamp and school nutrition programs, his Senate colleagues from both parties worry about how to keep the farm program in business. On the campaign trail, however, Helms told farmers he “saved” the tobacco program. And he says his promise to them to stay as Agriculture chair is the only reason he didn’t become the new head of the Foreign Relations Committee. U.S. farmers will regret this promise; soon after the election, Helms admitted he was “working on a farm bill that will establish the principles of free enterprise in farm programs.” His “market-oriented policy” will likely hasten the consolidation of farming under the control of large producers, who are among his most generous financial supporters.

LEGITIMACY AND SELF-INTEREST

Old Right money, tactics, and ideology thoroughly permeate the Ellis-Helms machine, even more than his critics suspect. But so do the moralistic rhetoric and computerized sophistication of the New Right. Indeed, the Old and New merge together in Helms more than in any other national politician. He consciously tied the traditions together by calling his Senate campaign “the conservative cause, the free-enterprise cause, but most of all, the cause of decency and honor and spiritual moral cleanliness in America today.” And on the Senate floor he consistently promotes the most extreme causes of the Old and the New Right, from tax breaks for segregationist Christian academies to foreign aid for Bolivia’s military dictators.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Jesse Helms is his capacity to embrace the entire spectrum of right-wing organizations and their causes. Jerry Falwell has said he is “troubled” by the senator’s refusal to support foreign aid for Israel; but Helms’s anti-Israel votes and leadership against the Genocide Treaty have earned him the admiration — and financial backing — of the anti-Semitic Liberty Lobby. Similarly, while other conservatives (including the Birch Society and Unification Church) have spumed the Nazi-affiliated World Anti- Communist League, Helms remains a steadfast friend, co-hosting the League’s U.S. conference in 1974 and heading the U.S. delegation to its 1983 conference in Korea (the destination of the ill-fated Flight 007).

When Jim Hunt aired ads linking Helms to “a nationwide network of right-wing extremists,” the senator responded with a characteristic shrug — “He is attacking the good Christian people on my side” — and a counter-charge — “We ought to talk about the ‘wrong-wing’ extremists [who] have a quid pro quo for every nickel they give” Jim Hunt.

As the self-proclaimed “point man” for right-wing America, Helms repudiates none of his followers — and consequently he can turn to all of them for money. He champions all their special causes and offers a shield behind which they can fight as legitimate actors on the stage of national politics, even if only from the right wing. Twenty years ago, Barry Goldwater bankrolled his rise to prominence by giving legitimacy to the issues and world-view of a network of groups that ranged from the John Birch Society to the Christian Crusade. Goldwater’s loss in 1964 did not diminish the Right’s search for a means to turn its self-centered ideology into national policy. As William Rusher, publisher of the National Review, explains: “Goldwater’s landslide defeat by Lyndon Johnson was of course a bone-crushing disappointment, but it did not alter the fact that, in the process of drafting Barry Goldwater, conservatives all over America had gotten to know each other. The mailing lists accumulated during the Goldwater campaign were the foundation of all subsequent organized political activity on the part of American conservatives.”

Richard Viguerie used Goldwater’s lists to begin his direct-mail empire; and in 1976, disillusioned with the Republican Party, he vainly offered to raise millions for George Wallace’s American Independent Party if it would nominate him as president or vice president. A decade earlier, in 1966, a front group for the John Birch Society calling itself “The 1976 Committee” announced its plan to build “an anti-communist, antisocialist political movement” in the Goldwater tradition by promoting a ticket of Ezra Taft Benson and Strom Thurmond. Such efforts have repeatedly been doomed by what former Senator Thomas McIntyre calls the Right’s “amateurism and rampant, highly exposed overzealotry,” and by what conservative Richard J. Whalen calls its inability to build a popular base and thereby transcend its internal weakness of being “long on self-appointed leaders who [are] egotists, dogmatists, hucksters, and eccentrics.”

Senator Helms pleads guilty to the charge that he is an uncompromising zealot: “If you are not willing to stand up for what you believe,” he likes to say, “then your beliefs are not strong enough.” And he doesn’t seem to mind his dismal record in getting his ideological causes enacted by Congress. Instead of changing the public character of rightwing leadership, as President Reagan has done, Jesse has managed to turn his “weakness” into his most bankable asset. And this, too, is the meaning of his money.

For him the goal is not winning any particular skirmish; it is the ongoing war that counts. Through his adroit use of parliamentary procedure, he repeatedly succeeds in drawing attention to his causes — and to himself as their prime champion. He succeeds in polarizing the Senate on recorded votes which he and his allies can use in later campaigns against those who are “wasting taxpayers’ money” or “supporting communist regimes” (the line Tom Ellis used to replace Robert Morgan with Senator John East). And, most importantly, even in defeat he can go to his supporters and raise more money with a story-line about his valiant efforts against “the entire liberal establishment.”

It is a devious but lucrative business.

Even those Republicans and rightwing leaders who might be inclined to repudiate Helms’s grandstanding as an ineffective vehicle for conservative political power are slow to criticize him. Again, money makes the difference. Because if Helms pauses from his pet projects to join them in the fight against the Panama Canal treaty or the maintenance of a Republican-controlled Senate in 1986 or the election of a President Jack Kemp in 1988, it means the addition of millions of new dollars and the Ellis-Helms propaganda machine to their cause. As an “independent” PAC, the National Congressional Club poured $4.5 million into Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential bid. The ability to move around that kind of money obviously gives a person considerable clout.

Jesse Helms is not yet chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, nor does he control the Republican Party. But his ability to raise unprecedented amounts of money from a nationwide constituency not only brought (or bought) him his re-election; it establishes a place at the highest levels of national politics for a right-wing extremist to shape public policy and debate.

How far he and his allies can go is the battle for the future. But don’t expect Helms to ease up and rest on his laurels. He is, after all, a free-enterprise politician in the business of taking big risks for high stakes. His national crusade against CBS and his “Operation Switch” campaign to re-register North Carolina’s Democrats as Republicans illustrate his ambitious agenda. Both efforts are the focus of major new direct-mail solicitations by the Ellis-Helms fundraising machine. And that machine, too, is propelled by a commitment to the logic of free enterprise. The Congressional Club-Jefferson Marketing complex of groups has nearly 200 employees, and it must constantly market new causes with saleable stories to keep millions coming in month after month.

This total, highly successful merger of politics and business, of ultra-right extremism and an ever-expanding mass-market enterprise, is the final meaning, the power, and the horror of Jesse Helms’s money. □

* As of November 26, 1984, the candidates had reported these figures; later reports filed by January 31, 1985 may put the total at $30 million.

Tags

The Campaign Finance Project

This article is part of a series by the Institute for Southern Studies’ Campaign Finance Project, produced in conjunction with the N.C. Independent with research partially funded by the Project for Investigative Reporting on Money in Politics and the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation. It was written by Bob Hall with the assistance of project director Marcie Pachino. Chief researchers were Ruth Ziegler and Chris Nichols. (1985)