This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 2/3, "Older Wiser Stronger: Southern Elders." Find more from that issue here.

"Elderly people really need that. I support it for the sake of the community."

Fred Chunn, 71, is talking about an unusual community transportation project. A combination of grassroots initiative and supportive local transportation officials has resulted in an innovative, community-run transportation service for Madison County, Alabama. The citizen-designed program began as a service for isolated, rural elderly and low-income Alabamans. Now operating in poor urban areas as well, the volunteer program is gaining the attention of transportation experts in many states.

It all started in November 1980 when G.W. Jones, from the small black community of Triana, made a telephone call to Ira Doom, coordinator of public transportation at the Huntsville Department of Transportation. Jones had a simple question: was there any way the department could help him get a van so he could provide medical, shopping, and recreational trips for low-income citizens in his community?

"Transportation was Triana's biggest need," explains Jones. "It's 22 miles to the nearest grocery store. If someone had $50 to spend on groceries, they'd have to pay someone $10 to drive them there. Now they can go for 50 cents round-trip."

From Jones's inquiry sprouted the idea of a community-run project, and Doom liked it. He scouted around, and with the cooperation of the Huntsville-Madison County Senior Center, arranged for an idle van to be loaned to Triana on an experimental basis.

With Jones's leadership and the enthusiastic support of the Triana residents, the project flourished. Soon news of its success spread to the neighboring community of Madison, and citizens there put in a request for a van as well. Another "obsolete" van was secured, and another public transportation project got underway.

Recognizing an idea with great potential, Jones and Doom put their heads together and developed the more formalized Huntsville-Madison County Volunteer Transportation Program, complete with operating principles and funding plans. The Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA), a division of the U.S. Department of Transportation, considers the program a model that can be replicated in rural and urban communities nationwide and has designated the Huntsville system a pilot program. Doom, as its developer-demonstrator, is assisting other local transportation officials to develop similar programs within their communities.

The program develops and targets transportation to meet the diverse needs of different groups of citizens; and it is sufficiently self-supporting — it doesn't lead to operating deficits that have to be made up by taxpayers — to be maintained in an era of tight budgets.

The overwhelming success of the Triana and Madison County projects has resulted in additional programs throughout the state. By the end of last year, 23 community vans were on the road in Alabama, and Doom has received approval of a grant proposal from UMTA for an additional 18 vans, to be put in operation this year. Florida and Indiana are exploring the possibility of starting similar programs in their states.

Mabel Thompson, 48, of Elkmont, Alabama, was the central organizer for the transportation project in her area and has served as chairperson of the board of directors since its beginning. "There was a crying need for transportation in Elkmont, but the town couldn't pay for a driver or a van," she says.

Once the people in Elkmont heard about the Huntsville program, "we didn't have much organizing to do— everyone jumped at it," says Thompson. "We had too many volunteers; we had to tell people to go away and come help later! The system's been a real blessing."

"The elderly especially appreciate the service. Their children work, and they hate to impose on them, but that means they end up staring at the four walls and become depressed. Having some way to get to the grocery and to the doctor lets them keep living at home, too. We have several that would be in nursing homes if not for the transportation."

One 77-year-old man in Elkmont was suffering from severe malnutrition because he had no way to go get food. "The poor man was just starving," says Thompson, "It added two years to my life to see him getting the help he needed. The program has enriched all our lives — not only the senior citizens but also those of us that are younger. We're helping each other."

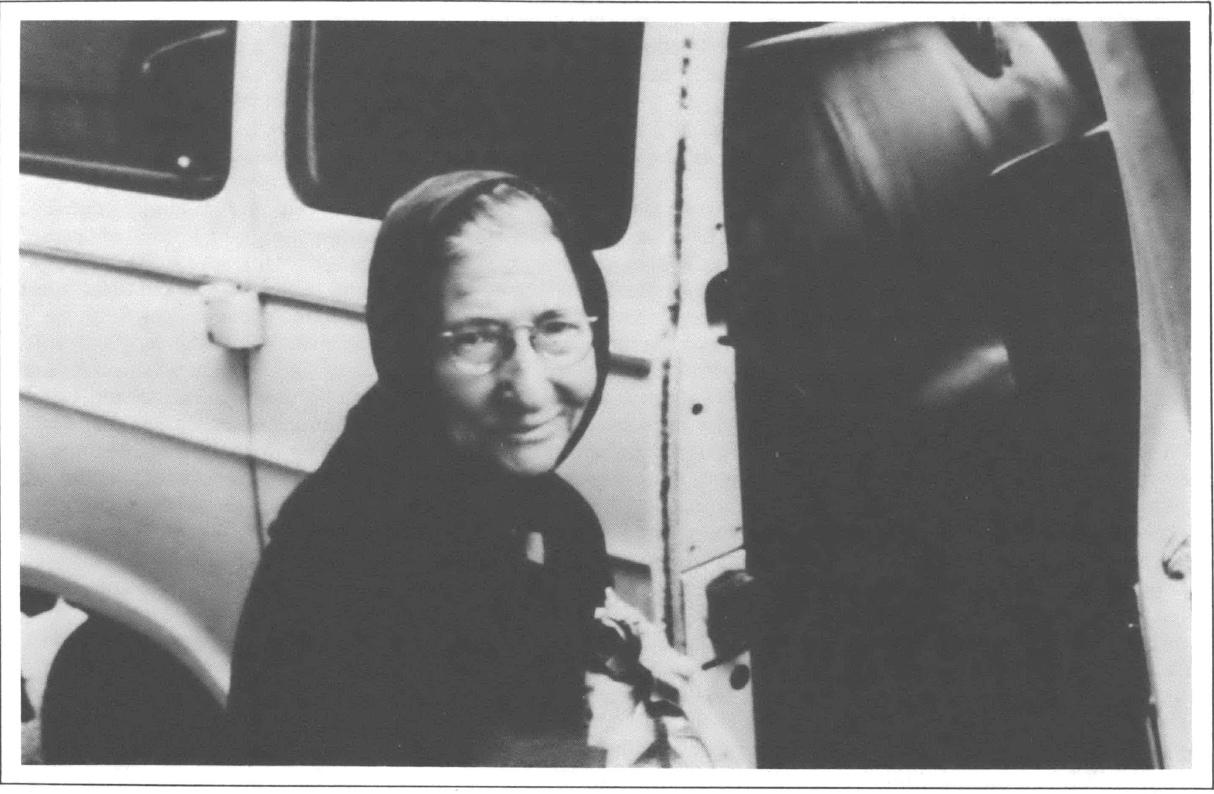

Eighty-five-year-old Luther Hargrove says the Elkmont vans have made all the difference in his life: "I was always at home by myself. I lost my wife — it used to get so lonesome. Now I have a way to get out. I go down to the depot [senior and nutrition center] almost every day, except Mondays, when I go to town, to the grocery. I guess I'm just about the oldest person on it, and about the only man, too." He laughs. "Most of them's women. I told them I was afraid they'd throw me out the window one of these times."

Managing a local project is relatively simple, but it requires the strong support of the communities involved. During initial formation, volunteer organizers work with Jones to locate community leaders and a network of reliable volunteer drivers. Thompson says that Elkmont had no trouble in locating either because the community was so sharply aware of its need for transportation. A federally funded nutrition program, housed in the renovated depot that is now Elkmont's senior center, was "about to fall apart because no one could get there. We were about to lose the nutrition center due to a lack of transportation for the people it was supposed to help," says Thompson. Helen Carter, another central figure in the transportation program's success, learned of the system in Huntsville and invited Doom to talk about it at the senior center. The meeting inspired an enthusiastic response, and a committee was formed to begin organizing the project.

Elkmont's six-member board of directors serves as an advisory body to the program officers and hears community complaints and suggestions. The four program officers have voting power to make decisions. Thompson stresses that the board meetings aren't regularly scheduled and that many management decisions are worked out by the riders and drivers themselves. Riders usually communicate conflicts that require board attention simply by phoning board members, who then schedule a meeting.

The drivers do minor van maintenance as the need arises — filling the gas tank, checking the tires and oil — and are responsible for arranging replacements if they cannot drive on their scheduled days. Many of the trip destinations, particularly for special events, are requested by one or more riders, and they are responsible for finding out how many people are interested in the trip. Thompson says that she encourages rider-initiated trips because "the participation is much greater when they come up with their own ideas."

All this communication has drawn the community together, she believes. "I've had older people say to me that sometimes they feel that they're not a part of the community — until they see the volunteers spending a day to help them. We had some teenagers this summer, helping the elderly in and out of the vans, up and down steps, walking them to their doors. It really brings the different age groups together."

"These communities have now got something they've really needed," says Jones. "It's made a big difference in drawing them together, because it's a group effort. When they need groceries, they call their neighbors and schedule a trip, then they go. This is something they manage and control among themselves. It's theirs."

Jones, who is now employed by the city of Huntsville as volunteer transportation coordinator, helps each group as it starts out — to raise funds, schedule its van trips, and meet safety requirements. His is a key role, best filled by someone who knows the community and potential leaders and is good at overseeing fundraising.

One method for starting out, Doom suggests, is to place notices of an initial meeting on residents' doors or in public places, then encourage those who attend to become leaders, organizers, or volunteers: "Groups likely to have success are those who take the first steps; generally they're motivated by family needs, and believe it or not, the desire to help their fellow man, most particularly their neighbors."

Each urban neighborhood or rural community furnishes volunteer drivers (who take defensive driving courses), raises the money to pay for gasoline, and schedules in advance the trips the residents want.

To help pay for fuel, each van has a donations can that riders contribute to as they are able. When funds are low the drivers only have to mention this and riders try to contribute more, Thompson says. Additionally, each community holds fundraisers: one group raised $1,100 on quilt sales, another got substantial church contributions, another secured $1,000 from a bank — all because the communities perceived the vans as theirs, Doom says.

Funds for van maintenance, insurance, and administration by the public transportation division of the Huntsville DOT are provided through a partnership of city, county, and federal government finding. In Huntsville, the city provides 20 percent of the cost of the vehicles, and all administration and maintenance costs; the county pays for insurance; and the federal government provides the other 80 percent of the cost of the vehicles.

There's a good deal of variety among the current projects, since each community decides what it wants for itself. The one element that they all have in common is that "control of the vans and determination of trip priorities are up to the individual community, as opposed to an outside agency that provides services," says Doom. "In short, the government provides the catalyst for neighbor to help neighbor. Lower-income citizens have proven that, given the opportunity, they can take care of their needs themselves and at the same time preserve their dignity. This is the only volunteer transportation program known to me that relies on a strong partnership between government, private enterprise, and volunteers, that involves several government jurisdictions — and that works."

Doom urges, "Every planner, town official and citizen involved in transportation should get to know local low-income rural and urban neighborhoods, seek out the leaders (they're there, waiting to be asked to do something for their neighbors), trust and respect them, and see what happens."

***

For more information about how you might set up a community transportation program, contact Ira F. Doom, Department of Transportation, 100 Church St, SW, Huntsville, AL 35801-0308, (205) 532-7440; or Roger Tate, Rural Transportation Program Manager, Office of Technical Assistance, Room 6100, URT-31, 400 7th St. SW, Washington, DC 20590, (202) 426-4984.

For additional information about innovative rural transportation programs and to receive the free monthly newsletter Rural Transportation Reporter, contact: Barbara Price, Rural Transportation Program Coordinator, Rural America, 1302 18thSt., NW, Washington, DC 20036, (202) 659-2800.

Tags

Deborah Bouton

A native of West Virginia, Deborah Bouton, 30, is a former editor of ruralamerica currently doing freelance work in the mountains of Vermont. (1986)

Ingrid Canright

Ingrid Canright, 22, was an intern with Southern Exposure and is now a journalism student at Antioch College. (1985)