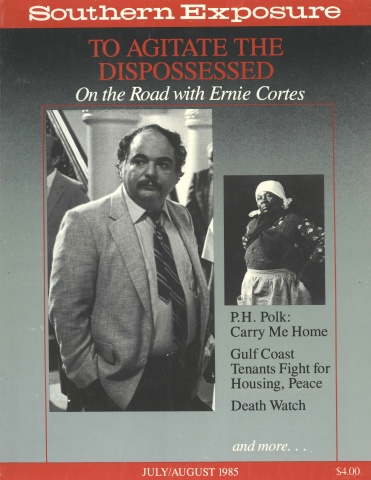

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 4, "To Agitate the Dispossessed: On the Road with Ernie Cortes." Find more from that issue here.

In my memory, there's a freeze frame of Ernie Cortes in the center of a sweaty, roiling crowd of students at the University of Texas. The air is as heavy as damp velvet on this summer night. We are packed into the small courtyard of College House, where the free thinkers live. I don't remember what Ernie says, just the urgency with which he says it. He wants us to support la huelga, the doomed Texas strike by the United Farm Workers.

Ernie looked the part of the barrio revolutionary in 1966. Not to mince words, he was gross and angry, and I'm sure he was considered dangerous by los rinches, the Texas Rangers, whom Governor John Connally brought in to help the Valley growers break the strike. When Ernie urged us to support the UFW boycott, we gladly banished lettuce and melons from our shopping lists. We also collected food and money and drove south in caravans, the 300 miles from Austin to the Rio Grande Valley, to march with the farmworkers.

Other Ernie fragments come to mind. I'm sitting at a table in a massive chicano ballroom in Houston, trying, over the reverberations of a conjunto band, to follow a conversation he is having in Spanish. Years later, he's imploring me to cover the first convention of a community group he has organized in San Antonio. Friends tell me of calls they receive from Ernie in the middle of the night: he needs a phone number, he's looking for a tape recorder, he needs a ride to the airport. Always, stated or implied, is the appeal, "Follow me."

His unrelenting drive and his power to motivate people made the journalist in me uneasy. So many '60s radicals turned out to be snake oil salesmen. Others became War on Poverty bureaucrats or lost their vision. Today Cesar Chavez meditates in the mountains while the UFW hemorrhages. But Ernesto Cortes, Jr., is still going strong. Some say with awe that he is the new Saul Alinsky.

When the MacArthur Foundation in Chicago decided last year to give Ernie one of its high-toned "genius grants," I decided it was time to follow him, at least for a while, because I had no clear idea of what a community organizer does. It turns out that Ernie has spent the last decade teaching people about self-interest politics, a skill which Americans, for the most part, have lost or abandoned. He believes that the traditional community fabric — family, church, political parties, labor unions, lodges — has come unraveled and must be rewoven into a new design.

"People have lost their taste for politics and the institutions in which politics are practiced," he says. Linking us together again is a colossal job, but the alternative is what we've got — Ronald Reagan and a public policy set by distant corporations, the mass media, pollsters, and political image experts. While all is gloom and darkness on the national front, the work being done by Cortes and others like him offers a glimmer of hope for our political future.

Ernie went to work for the UFW in 1966 primarily because Cesar Chavez had been trained by Saul Alinsky. Ernie's academic field was economics. After studying the various strategies for dealing with the poor, he came to the conclusion that Alinsky-style organizing of urban neighborhoods into self-sufficient power groups held greater promise for the underrepresented than did the government-financed War on Poverty or single-issue politics.

Alinsky's first book on organizing, Reveille for Radicals, was a best-seller in 1945. But Alinsky's real day in the sun came in the 1960s when college activists like Ernie adopted him as a hero. Alinsky was a brilliant agitator whose business card announced, "Have Trouble, Will Travel." A multicultural Jew from Chicago, he convinced the Catholic Church to finance many of his projects. Although trained as a sociologist, Alinsky grew to disdain social workers and government handouts. Uncomfortable with ideology, Alinsky simply wanted to teach the poor and what he called the "have little, want mores" how to solve their own problems and participate in their own self-governance. His personal sources of inspiration were Thomas Jefferson, Tom Paine, and James Madison.

Alinsky had a dream of building a national network of organizers that was not fulfilled in his lifetime. But his Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) established a training school for future organizers that may yet result in the network Alinsky envisioned. Cortes was admitted to the school in 1971, shortly before Alinsky died. Ed Chambers, a brusque former Catholic seminarian who succeeded Alinsky as national director of the IAF, recognized all the components of a good organizer in Ernie — intelligence, a basic anger about the way people are treated, and an orientation toward action rather than just talk.

Cortes's goal was to get something going in his hometown of San Antonio, which was 50 percent Mexican-American yet firmly under the control of the white business establishment's Good Government League. From 1971 to 1973, under Chambers' tutelage, Cortes honed his organizing skills among Hispanics in Chicago and Milwaukee and Lake County, Indiana. In January of 1974, under IAF sponsorship, Ernie returned home to San Antonio and began organizing the Catholic, Hispanic west side into a group now well-known as COPS (Communities Organized for Public Service). He emphasized church and family values more strongly than Alinsky, whose dominant theme was the duty of citizenship in a democracy, but his political tactics were vintage Alinsky.

When Mayor Charles Becker refused early on to meet with a delegation from COPS, Cortes took aim at the establishment that supported the mayor — the owners of the big banks and department stores. Five hundred folks wearing COPS buttons advanced on the Joske's department store next door to the Alamo. They tried on dresses and furs, experimented at the make-up counter, tested the beds in the furniture department, commanding the assistance of virtually every salesperson in the store. Over at the Frost National Bank, they lined up to change dollars into nickels and nickels into pennies and then back into dollars. COPS not only got its meeting with the mayor, it extracted a $10,000 loan from the president of the bank.

Texas Monthly magazine has since dubbed the COPS-inspired political realignment of San Antonio "The Second Battle of the Alamo." The current mayor, Henry Cisneros, like Cortes a native of the west side, has likened the power shift, which brought Mexican-Americans into full political partnership in San Antonio, to "turning an ocean liner around." Now, at the ripe old age of 11, COPS is probably the most potent minority-controlled civic organization in the United States. That's because COPS is concerned with more than new street lights and drainage projects. Jan Jarboe, a journalist from San Antonio, told me, "This is a story you are not unaffected by. There is a fabric, a texture of faith and hope that is not to be believed. It's an extended family. There are west siders today who are buried wearing their COPS buttons."

Nationwide there are now 15 IAF projects, three in the New York metropolitan area, two in the mid-Atlantic area, three in California, and thanks to Cortes's extraordinary efforts, eight in Texas, with more on the drawing board. While much has been written about COPS, Ernie has been a peripheral figure in most of the stories. Alinsky aside, most IAF organizers try to remain in the shadows. I reached Ernie by phone in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, the semitropical borderland where he was working with Valley Interfaith, one of the groups he now oversees in his position as a senior cabinet member of the IAF. I was in luck. The IAF had recently loosened its restrictions regarding interviews, and Ernie agreed to cooperate. He said that he and his wife, Oralia, and their two young children were moving to Austin, where I live, so I presumed we would be able to talk at leisure. I soon discovered, however, that Ernie is in perpetual motion.

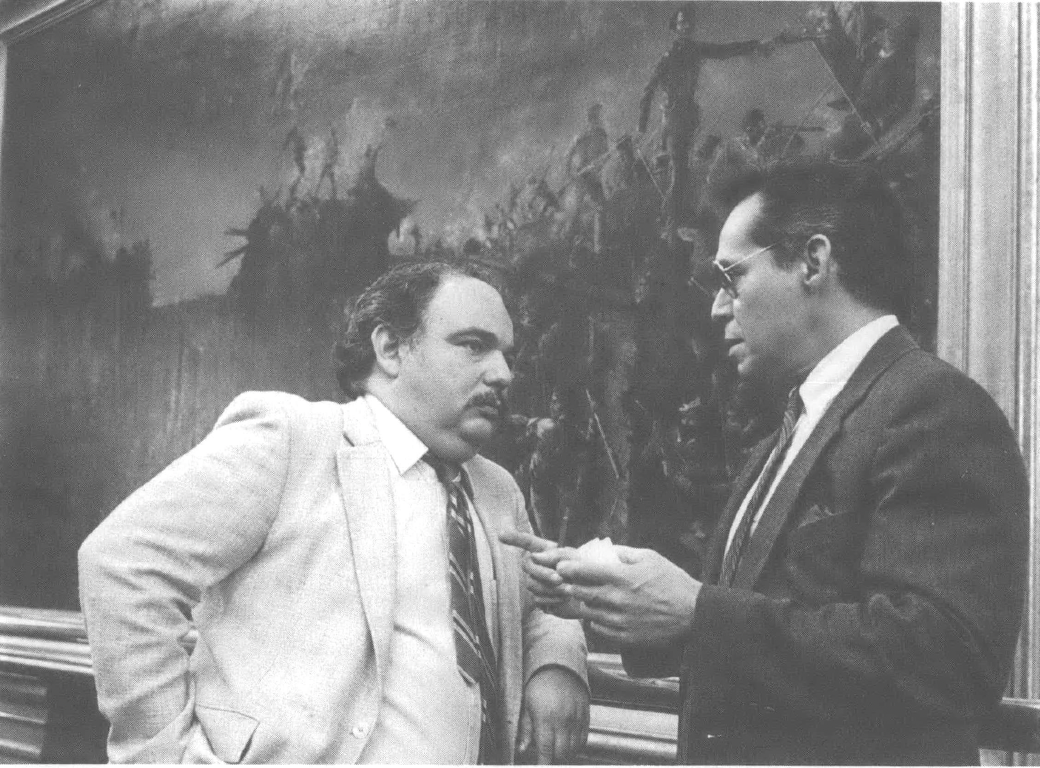

Over a two-month period, I traveled with him intermittently, snatching interviews on the run and watching him work. At the age of 41, Ernie dresses like a businessman. He is smoother around the edges than he used to be, although his manner is still abrupt and challenging. He has lost weight but still has enough bulk to intimidate, I was surprised at how religious he had become, a serious Catholic, and how much more teacher and strategist he is than rabble-rouser.

When I asked him what he was going to do with his $204,000 MacArthur grant, he said, "Buy books." Nobody can buy that many books, I told him. Now I'm not so sure. The Cortes house in Austin is a tumble of books and his Toyota is a library on wheels. He reads heavy-duty theology, sociology, psychology, philosophy, scripture, political biography, political theory, history, and economics. Christine Stephens, a crisp Catholic nun who serves as the IAF's lead organizer in Houston, told me, "I have known other brilliant people, but no one whose book knowledge is so useful as it is to Ernie. For him, it is a positive addiction."

Every time I dragged myself home from a trip with Ernie, I pulled from the high shelves in the study previously untouched volumes of Britannica's Great Books series. No more murder mysteries for me, I vowed. From now on I'll read only worthy stuff. Slowly, it dawned on me that I had been agitated by a master.

My usual reportorial technique is to lay low and listen hard, but Ernie insisted on constant feedback. On the telephone, he would ask the open-ended question, "What's going on?" When I traveled with him, he wanted to know, "What did you think of the meeting? Was I too abstract? Did I energize people?" At first I tried to deflect his questions, but his response was an angry, "Don't shut me out. I can handle anything except no communication."

One of our few uninterrupted interviews occurred the day I chauffeured him from San Antonio to a lodge perched at the edge of the Frio River in the Texas hill country. I met him at the San Antonio airport. As usual, he was the last person off the plane and he was dragging three satchels of new books. A female skycap and I loaded a tiny suitcase and all those books onto a dolly and hauled it to my Volkswagen as he made calls from a pay phone. On the way out of town we stopped at a shopping center so Ernie could get a pair of reading glasses and some lozenges for a persistent cough. (Constant travel, too little sleep, and irregular eating habits seemed to leave him vulnerable to flus and bugs and respiratory problems.) It was like playing hooky, stolen minutes at the drug store while we were supposed to be on the road to his next gig.

It was a fine evening. We were well into the country now. To the north and west were the low, cedar-covered hills of central Texas. I was filled with contentment by the twilight, the soothing, empty land, and the highway ahead. It was a good time for intimate questions. I asked Ernie about his family.

Ernie's voice was hoarse, but the lozenges seemed to be helping. He cleared his throat and spoke into the tape recorder over the road sounds, "My father's father was the police chief of Mexico City. The family came to Texas in 1910, during the Mexican Revolution. My mother's family also came from Mexico, but she was born in Texas.

"Dad worked as the manager of a Payless drug store in San Antonio and for the Pepsi Cola Company. Then he lost his job in the recession of '53-'54, and the only reason we were able to keep ourselves on top was that we were an extended family. My mother's father had a little business and he took my father on. My family tried very hard to fit in, but I could identify as a Mexican more easily than as a Texan or an American. I saw a lot of discrimination against Mexican-Americans in San Antonio. . . . I had an invalid sister who lived with us until she was 12, when she died. Part of who I am has to do with my identification with her. Other people looked down on her. My mother said I had fights with my friends when they looked down on her."

"What makes a good organizer?" I asked him. "You don't have to be educated, but you have to be smart," he said. "One of the qualities that you can't teach is anger. I'm talking about anger that comes out of a concern for other people, not just yourself. If that isn't there then you don't have the patience to build an organization. It's a cold, calculating kind of anger. I equate it with the anger of Moses." As an afterthought, he added, "You also have to have a sense of humor. If you take yourself too seriously, you get self-righteous, rigid, overly principled."

I tried to remember what made him laugh. He laughed at politicians a lot, but he had the good sense to put me off the record before doing an imitation of some sputtering councilman flailed by one of his groups. Earlier in the drive he had described a meeting with a delegation of right-wing Catholics and business people who are convinced that he and the IAF are Marxist revolutionaries or some such nonsense. Ernie, laughing and slapping his thighs, had recreated an exchange with one of them. "I know what you're up to, young fella," he mimicked one of his adversaries saying. "You're smart. You're very smart. How much do they pay you?" "About $45,000 a year," Ernie answered. (Senior IAF organizers no longer live on subsistence wages.) "Well, you're worth every penny of it," the fellow concluded.

The sun was behind the hills now, and I was on the lookout for deer on the highway. Ernie seemed oblivious to the scenery. His attention was always trained on his work or on information that could help him in his work or people who are involved in his work. I was curious about the price his family might be paying for his success. He obviously dotes on his two young children and his teenaged daughter from an earlier marriage. Was time with his family a problem? "It could become one," he said. "Oralia tells me, 'Come back before your children forget what you look like.' I have to set aside time for them. I try to take one day off a week." I knew from Oralia that after many years of effort she has convinced Ernie of the need for a yearly vacation, preferably to a foreign country where he has difficulty placing telephone calls.

I asked him what he hoped to be doing 10 years from now. "I'd like to see more of these organizations throughout the Southwest putting together a regional strategy about water, energy, and employment," he said. "The chronic unemployment and economic stagnation along the U.S.-Mexico border is very significant. I'd like to be able to have some organizational relationship with the people across the border. Right now, I have no idea how to do that, but it's something I would like to figure out. And I'd like to have thought deeply enough about politics to be able to write and teach about it in a systematic way."

We pulled into the lodge 30 minutes late, meaning no time for dinner, as usual. About 50 employees of Texas Rural Legal Aid (TRLA), most dressed in jeans, T-shirts, and jogging shoes, were drinking beer in a meeting room filled with church pews and lumpy couches. The TRLA, a federally funded agency which provides legal assistance for the poor along the Texas-Mexico border, had invited Cortes to speak at their annual retreat. Ernie was tired when he arrived and his sinuses were draining so profusely that he could hardly keep his throat cleared, but he slowly recharged as he paced across the front of the room like a bulky, short-legged bear, speaking very rapidly as he laid out the complexities and contradictions of his work.

Ernie emphasized that he wasn't building a movement. "Movements address a single issue and are built around charismatic leaders. When the leader dies, the movement dies. Okay?" he asked his listeners. Were they understanding? He explained that the IAF builds power groups based on Judeo-Christian values rather than issues. There are no individual memberships, only institutional memberships. They do not accept government grants, because too many restrictions come with the money. Today, he explained, the IAF relies on churches as the primary source of funds and troops. "I organized civic groups in Chicago and East Lake County, and after four or five years, they went out of existence because they had no source of continuing funding. All right?" Ernie asked the lawyers.

He ran through his points rapid fire, occasionally writing something on the chalk board for emphasis. "The churches give us stability," he said. "All of the sponsoring churches believe in making a preferential option for the poor, the people who in a biblical sense have not yet come to the table. Christ said, 'My kingdom is not of this world.' He was the good shepherd who brings his flock into the life of the community." Each of the Texas IAF groups, he said, has a different complexion and advocates different issues. Allied Communities of Tarrant in Fort Worth is primarily black and Baptist. The Metropolitan Organization in Houston is white working-class Catholics and Protestants. Valley Interfaith, which is Hispanic, is financed by 29 Catholic and two Protestant churches.

Ernie explained that his job is to train and counsel the IAF organizers who work with the Texas groups. He also conducts workshops on politics and power for the volunteer, unpaid leaders of the various groups, who regularly work 20 to 30 hours a week for the organizations. "They do it for a sense of power, recognition, and importance," he said.

"The people I organize tend to be poor or Hispanic or black and tend to be conservative about family, neighborhood, and church. I'm the radical," he said, arms out from the sides of his body, fists clenched, standing like a wrestler poised for an attack. "My job is to agitate the conservatives. I tell them that if they don't get organized, they will lose everything."

He explained that while the Texas groups registered 105,000 new voters in 1984, they are proscribed from endorsing political candidates because they are funded by charitable contributions. This is not a handicap, Cortes said. "Our political position is that neither party is addressing our issues. Our purpose is to frame the political debate by endorsing issues, not candidates. Okay? An organization like COPS can be the conscience of the politicians, who can lose their souls if someone doesn't hold them accountable."

He has said on another occasion, "We like to think that we are engaged in politics in the fullest sense. That means beyond electoral politics. We are trying to have a say in the everyday process of decision-making."

The lawyers, many of whom represent farmworkers in the Rio Grande Valley, wanted to talk about Valley Interfaith, which, since its inception three years ago, has emerged as the dominant unifying force for Hispanics, not simply for the poor but for the long-ignored Hispanic middle class along the Texas-Mexico border. The area has been financially wrenched by the double whammy of Mexico's economic collapse and by a devastating freeze in the winter of 1983-84. Unemployment rose as high as 35 percent in an area where a quarter of the population already lived in poverty. Ernie Cortes and Valley Interfaith responded with a proposal for $67 million in federal and state public works funds for local governments to improve roads and sewers and water lines throughout the Valley. While only a trickle of government money has been forthcoming, Valley Interfaith has achieved something unique. For the first time in memory, the Balkanized Valley towns, as well as church and civic leaders, joined in a common political cause. The mayors of 15 towns are now meeting regularly to work on a Valley-wide economic strategy.

Some of the lawyers seemed uncomfortable with or jealous of the clout already evidenced by Valley Interfaith. A willowy woman lawyer told Ernie, "When you get involved with a project, you want to run with it. Don't you ever take a second-place role?" Cortes pointed out that the group had taken second chair in lobbying with the UFW and other groups in a successful effort finally to get farmworkers insured under workers' compensation. But, he added, "We don't like to get involved where we are supposed to be the troops for someone else's expertise. All right? We don't usually work for losing causes. We are not here to do good. We can't right every wrong, but we can teach people how to be effective and organized. The most important thing we do is locate and train a sophisticated collective of leaders."

"How can we lawyers work with you?" came a question from the back of the room.

"We don't like to go into court as a last resort," Ernie said. "Only lawyers can have fun in court. What we want to do is to train our own people to participate, to argue, to negotiate, to bargain, to make decisions. We're wary of the tyranny of the expert."

It was obvious that some of the lawyers, young and idealistic, didn't get it.

"But what's your ideology?" somebody asked.

"I don't know," Cortes said.

If I could have broken in then, I would have made the point that Ernie invests in people rather than issues. He agitates the dispossessed to anger and then shows them how to channel that anger into the public dialogue. "If we are about anything," Ernie had told me, "we teach people not to be fatalistic. I like teaching so-called uneducated people fairly sophisticated political concepts."

He frequently must play the heavy, agitating people to learn political lessons. He told me about a confrontation with one of his closest friends, Father Albert Benavides, who was a leader in COPS. Benavides led 300 COPS people to a San Antonio city council meeting to talk about protection of the Edwards Aquifer, the city's underground water supply. Then-Mayor Lila Cockrell had told Benavides by phone that COPS representatives would not be allowed to speak until very late in the day, meaning after the news reporters had written their stories. Benavides knew that he would lose his troops if they had to cool their heels all day long.

Cortes told Benavides that he had two alternatives: he could seize the microphone and demand that Cockrell hear them or he could send everybody home. Benavides said, "I'm not gonna do it. She'll throw us out or worse." "Father," Cortes shouted, "you don't need an organizer, you need a baby sitter." Ernie angrily signaled the COPS leaders to come out in the hall for a caucus. Then he heard an amplified voice from the council chamber. "Father Benavides was busting up the meeting," Ernie recounted, laughing with delight.

To Cortes, the victory that day had more to do with Benavides getting up the gumption to challenge authority than with clean water. In his mind the issue is never as important as what people learn through dealing with it. When COPS was first getting started, its members had to use confrontational techniques to gain attention. Today, with the urbane Henry Cisneros in the San Antonio mayor's office, COPS plays a much more sophisticated political game.

During the summer of 1984, the Texas groups were part of an unlikely coalition that successfully lobbied in Austin for legislation that will allocate more state money to poor school districts. The coalition put Interfaith in alliance with Governor Mark White, Dallas billionaire Ross Perot, and conservatives Bill Hobby, the lieutenant governor, and Gib Lewis, the speaker of the House. It was not unusual for 15 to 30 IAF leaders to attend a strategy session with the governor or the lieutenant governor. Ernie viewed the sessions as a graduate program in lobbying and political power. After every meeting there would be a rigorous evaluation of the effort. Exactly what had the governor promised? Was there a better way to have made that point? Why had Mrs. X's presentation gone nine minutes rather than five? COPS leaders used to videotape their appearances at city council meetings and later critique them, like a football team after a game. "People will naturally make a lot of mistakes," Ernie says, "but we use the mistakes to teach people something." When the school finance program passed, the legislature was applauded by a gallery packed with Interfaith members.

When Governor White went to McAllen last summer to meet with Valley Interfaith about school finance, health care, jobs, and other issues important to the economically depressed area, 6,000 people attended the meeting. Six thousand organized voters command a governor's undivided attention.

While they were allied with White on the issue of school finance, the Texas Interfaith groups have held the governor's feet to the fire on other matters. There is nothing a Texas politician dislikes more than an IAF "accountability session." The sessions are carefully staged public forums in which designated hitters — housewives, priests, nurse's aides, and other big-time wheeler-dealers — question an elected official or candidate unmercifully until he or she is forced into an actual commitment on an issue of concern to the group.

The Interfaith groups are dedicated to the proposition that politics should take place in public. Hundreds of COPS people may attend a meeting with a city council member. COPS controls the meeting. The public official will be allowed only a short general pitch and then is asked to respond to specific questions on issues. Anyone who has tried to get a yes or no commitment out of a planning commissioner or city councillor will appreciate the dynamics of an accountability session. Cortes says, "I've seen professional lobbyists get firm commitments out of politicians, but the public usually can't."

The sessions, which are very formal, teach average citizens how to deal effectively with powerful people. Many politicians come away from these carefully staged political dramas feeling they have been treated rudely. Ernie says, "Politicians are past masters at seduction. It's important for my groups to learn about boundaries. You must come into a negotiating session with the attitude, 'You are not my buddy, at least not at this moment, so don't ask about my grandmother and my family.' People in business learn this right away, but when poor people do this they are being rude."

Austin attorney Pike Powers, who is a key player in the local power structure, got acquainted with Ernie and the Texas Interfaith network while he was executive assistant to Governor White. Powers is savvy enough to realize that the new group Ernie has moved to Austin to organize could become a fly in the ointment, or worse, a rattlesnake in the bathtub. When San Antonio mayor Cisneros was in town last September, Powers got him to speak to a group of Austin businesspeople about Ernie and his organization. "Ernie is always more effective than the people who have been here before him," Cisneros says he told them, "because he comes in and asks people what their problems are, rather than telling people what their problems are. He has a grassroots certainty about his methods and his information."

At that meeting, someone asked Cisneros, "What is he [Cortes] after?" "I tried to describe a vision that is not radical but is rather a vision of democracy," Cisneros remembers. The mayor added that Austin Interfaith will have to be dealt with, that it will not be a flash in the pan, that its research will be first-rate, and that even if Austin Interfaith adopts a strident tone at first, it will be playing real-world politics and will be willing to compromise.

Cortes's work is really an ambitious adult education project. I was encouraged by the fact that people seem so receptive to the training. Frank del Olmo of the Los Angeles Times apparently reacted similarly when he wrote a series of articles on UNO, the United Neighborhood Organization in Los Angeles. This is a group that Ernie organized after COPS. Del Olmo wrote, "Time and time again in talking with UNO leaders, an outsider is struck by how often they cite their own personal growth and the growth of their friends as one of the benefits UNO has brought to their community." In the same vein, Mayor Cisneros told me of watching San Antonio housewives transformed via COPS into formidable leaders.

Ernie encourages his people who can read (and some can't, either in English or Spanish) to keep up with the local newspapers. And for those who are willing to do more, Ernie the insatiable reader recommends books — Bernard Crick's In Defense o fPolitics; Robert Caro's study of Robert Moses, The Power Broker; T. Harry Williams's Huey Long; Ronnie Dugger's LBJ book, The Politician; The Human Condition, by Hannah Arendt; Ortega y Gasset's The Revolt of the Masses; The Efficient Executive, by Peter Drucker; Saul Alinsky's Rules for Radicals and Reveille for Radicals — the list goes on.

Most of the current COPS officers are women, and Cortes describes them proudly as "barracudas." Three of the IAF organizers in Texas are talented nuns, who have a better opportunity for leadership in the IAF than in the Catholic Church. Why are so many of his star pupils women? "Saul Alinsky's goal was to teach have-nots how to negotiate themselves into the system," he said. "As soon as you're successful, you go agitate somewhere else. It's an endless process. Alinsky said men think in terms of projects with fixed points. Women are more circular. They are the ones with the patience."

The church's role in IAF organizing at first perturbed me. But this is far removed from the Jerry Falwell/Moral Majority brand of politics. In the meeting room of a Catholic Church in El Paso, I watched Ernie teach the concept of pluralism. "There's a religious undergirding to our political beliefs," he said. "But the church teaches you to work with atheists and agnostics who share your goals. The founding fathers were religious and agnostic at the same time." At a training session for leaders in San Antonio, he said, "Once you have a single view of something, you are no longer in politics, you are in anti-politics."

While many of the Catholic bishops in the North tried to claim abortion as the pivotal issue for Catholics during last year's presidential campaign, the IAF organizations homed in on jobs as the issue. Indeed, their refusal to get hung up on the question of abortion has resulted in red-baiting of the IAF groups in El Paso and the Rio Grande Valley. The Wanderer, a right-wing Catholic newspaper based in St. Paul, Minnesota, has been responsible for some of the attacks.

If I can fault Ernie for anything, it is that his sense of mission sometimes makes him intolerant and overbearing. I saw him attempt to lead IAF leaders to certain political or organizational conclusions. At an El Paso meeting, he asked a question to which a priest replied, "I know what you want me to say but I'm not sure I want to." What about that exchange, I asked Ernie. He said, "It's not supposed to be like that. It's not supposed to be fill-in-the-blank." I heard him deliver some very harsh judgments on gays, feminists, environmentalists, and others who pursue the kind of single-issue politics he thinks has crippled the Democratic Party. A feminist, an admirer of Ernie's, told me she approached him in an airport and introduced herself. "I know who you are," he answered, and walked off. Here is a man whom Christine Stephens says showed endless patience as her teacher. Perhaps he expends all his patience within the circle of the IAF.

Whatever personal flaws Ernie has, he's still the real thing. Stephens pointed out, "The stereotype of the organizer is that they are manipulative, uncaring, brash, rude people, but underneath it all Ernie has a real commitment to unlocking people's hidden resources." Traveling with him, I found myself wondering, "How is his health? How many people can he organize in a lifetime?" Fortunately, this work is designed to be self-perpetuating. So let a thousand Ernies bloom.

Tags

Kaye Northcutt

Kaye Northcott is a journalist whose work has appeared in numerous publications, including Mother Jones, Texas Monthly and many others. She was editor of the Texas Observer from 1968 to 1976. (1985)