Soapstone

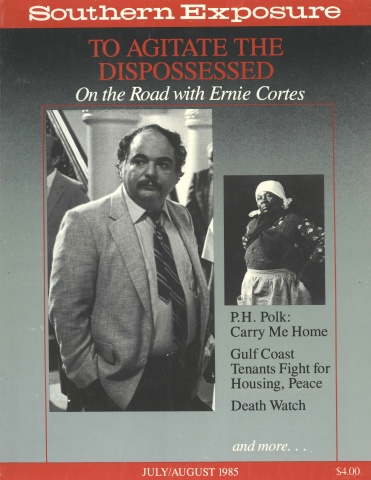

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 4, "To Agitate the Dispossessed: On the Road with Ernie Cortes." Find more from that issue here.

Earl built the house. His two brothers-in-law helped him as much as he needed. He built it on a quarter-acre of near-vertical hillside. The house was tricky to build. The whole structure hung out from the mountain, beneath a steeply cut road.

The five rooms were supported on a trestle of beams anchored in rock. The whole time Earl was hammering it together, he could look below and see the fall the house might take into the creek. He drove every spike and nail with the anxiety of a craftsman out on a limb. He was unconcerned with the beauty of it. If it held together it would be beautiful enough.

Earl was a carpenter. He built the house one summer, evenings after work. At work he ran a rock saw, slicing blocks of soapstone into slabs. He left for the quarry before dawn. He would walk to the railroad spur and ride a flatcar to the quarry. The soapstone was an amorphous gray rock that cut easily into flagstones, powdering into talc beneath the great saw-toothed blades. At the end of the day he returned home and cleaned up, and then walked over the mountain and sawed and hammered wood until the light foiled. Then he went to dinner.

The finished house was extremely solid. Earl could barely feel it vibrate when all five of his kids pranced up and down on it at once. His wife could walk on it without fear. The trestle could have held a much heavier house and still been secure.

Earl moved his family in, and they were happy. "It was worth it, Earl," his wife said. "We don't have to pay hardly more than the rent was, and it won't be but a few years before we don't have to pay that."

"Don't get set on it," Earl said. "The soapstone company owns this house until we finish paying for it."

"We've needed a bigger house for a long time."

"Don't get set on it, Edie. I don't trust them."

The house and land together had cost almost a thousand dollars. Earl's pay came mostly in the form of scrip for the company store. Until he moved, the company had also been his landlord. The money for Earl's house had come from a company loan.

Earl knew how risky it was to get caught up working for the soapstone company. His carpentry was a good deal safer. Getting out of the soapstone company's employ was not easy. They still owned you if they fired you. He was well aware of that. Like everybody else who worked there, he was stuck. He had to work where he could.

Mr. Wright, the head cashier who made the loan, was also stuck. Not many cashiers were so steadily employed that year — it was 1934. The man who owned the mine, Mr. Tapley, was stuck too. The company was like an old whore, 75 years venerable, and had been owned many times. The business of the quarry, which had been all vigor and expansion only a few years before, was slowly sinking. Even the rents from the company housing were getting harder to collect, just when every dime suddenly seemed to matter.

Wright came to think of the loan in a new light when he transferred Earl's name from the column in which the rents were entered. The loans were finite; the rents weren't. Still, it all seemed to balance out; there were plenty of people to rent to, and the loan held Earl as tightly to his job as rent would do. But something in the idea nagged at him.

"What are you so lost in thought for, Jim?" Mr. Tapley asked.

"I was just looking at these books."

"Did you find anything?"

"I just think there ought to be a few more dollars in here than there are."

They were both always aware — sometimes vaguely — of the iron safe in the corner. Taller than a man, the massive metal doors enclosed much of what the company was worth in titles and contracts and payrolls. The combined mass of wrought iron and paper wealth, so intricately locked up, was too much to forget.

"I agree," Tapley said. "There ought to be some way to milk those numbers up another decimal somewhere."

Wright went to bed thinking of that problem. He smelt a four-figure increase somewhere, and he would have been derelict in his duty if he rested comfortably before he found it.

The next day he drove over the mountain and looked at the house Earl had built with the company's money. Then he drove back to his books.

Earl was already suspicious when he came home from work. He could feel things going wrong.

"I saw Mr. Wright drive up the road today," Edie said.

"Mr. Wright drove up the road?"

"And back."

"Looking at the house," Earl said. "Son of a bitch." The shrill cry and thunder of the children trying to dismantle the place from the inside distracted him. "Shut the hell up in there," he shouted.

"Does it mean anything, Earl?"

"It means we're living in a fool's paradise, that's all."

Edie took the water buckets and went down to the spring to fill them.

Earl slept very little that night, and he went to work uneasily in the morning. The loud whine of the rock saw did nothing to soothe his nerves.

Within distant earshot of the saw, Wright and Tapley were discussing Earl. The brass handles and gilt curlicues of the black iron safe resembled the mouth-parts of a giant crab, in the corner behind their backs.

"I think we should reconsider that loan," Wright said. "It wasn't a good loan."

"I don't see what we stand to lose," said Tapley. "We've done it before. This kind of loan works out just as well as anything else."

"Usually. But usually what these people do is throw together some flimsy shack that might not last out the terms of the note. That's why it works out so well. By rights a place like that ought to have slid into the creek before he was finished building it, and that's what's different here."

"What are you trying to tell me, Jim?"

"He didn't build a shack. He built a damned solid house, and it's worth at least twice as much as the nine hundred dollars plus interest that we'll get back out it, as things stand now."

"Well, maybe that's his good fortune," Tapley said. "We made him an honest loan, and he honestly did what he said he was going to do with it."

"I don't think it was necessarily so honest as that. What he did was take our thousand and build himself a two-thousand- dollar house with it. He might sell the thing and pay us off, and skip out tomorrow with a thousand-dollar profit scalped right off the top of our books."

A little light of irritation sparked up in Tapley's eyes. "I think I do see what you mean," he said.

"Earl's not so innocent. We're the ones that are being innocent. A thousand dollars is a lot of money."

"It sure is. We do have clear title to that piece of property, don't we?"

"It's right there in the safe."

"Call Earl's foreman in here a minute."

Earl went home from work early that day. He walked in the door and sat down in the rocking chair without cleaning the morning's stone dust off himself.

"I was right," he said. "The company let me go."

Half the kids were in school. The baby was asleep. The house was almost quiet. Earl's face was calm and unemotional — graven in soapstone. "Well, we had a chance," he said. "I guess it didn't work out."

Edie was not as calm. Her voice was frightened. "What are we going to do?"

"Look for a place to live."

"Maybe they'll hire you back."

"They will. In two months."

"You reckon they'll take the house?"

"That's what it's all for. Was all along. Building this house was a mistake."

There was little for Earl to do but wait for the end of the month. He couldn't stay in the house all day. He walked here and there along the river, down to the station, back up to the mill. Everyone knew his story. He knew their stories too. He was looking for work. The work was over the mountain, in the quarry. There was no other work. The played-out fields didn't need any more wasted effort. The station, the store, the mill had what hands they needed. They, too, were stuck. Good a carpenter as Earl was, nobody was building anything.

Earl went to see old man White, because White had an empty shack down below his springhouse. "They're going to hire me back," Earl said.

"I know they will."

"Why don't you rent me that house down there by the creek until I can get something fixed up better. I'll work on the place; the roof and the porch both need some work. The only thing is that damn first month's rent."

"Earl, that's fine with me," White said. "The place is empty. Take it and fix it up and I'll let you have it for five dollars a month, long as you want it. I got it wired for electricity. It's not so bad." White kicked an empty whiskey bottle off the porch.

"Well, at least I can listen to the radio at night."

"They're fucking you over right and left, Earl."

"I know it. I could kill the bastards with my bare hands, and it wouldn't be murder. I'd enjoy that, but what would become of my kids then?"

"You could break them in half, Earl. I remember when you were a fighting man. That time you fought old Aubrey was probably the best damn fight there was in these parts."

"There wasn't anything to Aubrey. He had a glass jaw. That fight didn't last six seconds."

"His jaw? You busted every tooth out of his head. He was the last man ever pulled a pistol out and called you a shrimp."

"I never did like to be called a shrimp. It was the pistol that did it, though. I don't care for guns. But I feel real bad about all those teeth of his."

"Hell, Earl, everybody in Rockfish was grateful to you. Old Aubrey was an asshole up to then, and it was just a matter of time before his pistol went off and hurt somebody. You improved his manners right sharp. Now he's so easy-going, sweet-tempered, and polite that you wouldn't imagine it was the same man. Even his gold teeth are prettier than the originals. You did everybody a favor when you busted Aubrey in the head — him too."

"That was ten years ago. I haven't got any pride left. I've got too many children."

"Yes, it's true, a family can slow you down considerably," White said.

At the end of the month Earl borrowed a cart and moved his family into the bushes down White's creek. A week later he heard that the soapstone company was hiring again.

"Are you really going to go, Earl?" Edie asked.

Earl's face was itself as hard as a stone. "I'm no happier about it than you are, but do you plan to eat next week or not? I already owe White five dollars, and I'm going to owe him five more in a couple of weeks. What else can I do? I don't want to talk about it."

Earl missed the train on his first day back to work, and had to walk the full five miles along the railroad track to the quarry. The day's first load of cut stone passed him on the way to the station, and he couldn't bring himself to wave back at the men on board. He regretted each step. He meant to kill the first man that showed any pity for him. The waiting saw seemed to grin at him. He worked. He cut stone. Clouds of talc flew up around him.

Late in the day he saw Mr. Wright watching him from the office door.

"I saw old Wright eyeballing me today," he said to Edie that night.

"Was it because you were late?"

"Hell no, it wasn't. They own my house."

"I swear, Earl. It's like there's no end."

"I don't believe there is an end. They're going to drive me into the ground like a railroad spike. Well, they won't break me. I'll draw my pay while I can."

"While you can?"

"They won't keep me long. Just long enough to make them feel decent."

"Maybe you're wrong."

"I'm not wrong."

"Maybe they won't feel decent too soon."

Edie didn't trust her husband's bosses at the quarry any more than he did, but she believed Earl would somehow handle them. She thought so because Earl was a hard and careful worker, and hard careful work was the system for doing good. She thought of Wright and Tapley as rascals who randomly did wrong, careless things. She didn't know they had a system too.

Earl didn't miss the train next morning. He kept telling himself that he was little worse off than he had been six months before. It was a lie he told himself, as he knew. He was worse off, because he would be fired, this time permanently. He would be fired because they had stolen from him. As the days went by, he could tell when they were talking about him up in the office. The concern they had for him moved him greatly.

"We can't hang onto him forever," Wright said. "He isn't moving back into a company house. That's ten dollars a month we lose out of his pay. It's not efficient."

"I wonder if it's good to let him go," Tapley replied. "We made twice the amount of his salary off of him this year. It seems cruel to fire him on top of that."

"He still wants to skin us. Look, he's down there with a mighty expensive saw. He broke a blade already since he came back. These people don't understand business. He thinks this is personal. He holds it against us."

"How can you tell?"

"He comes in and goes right to work. He doesn't talk to anybody. He doesn't look around. He doesn't even look up. His attitude is bad, and he's going to try to get even as soon as he can."

"We can't have it, then," Tapley said.

"We can't, that's true. Even this business of the lost rent. Our books don't look so good any more. That stack of orders over there is shorter every week. This is one hell of a blight we're in."

"Sometimes I think we're going down," Tapley said.

"We will if we don't dance fast and pick up every loose dime we can. It's that bad. And people like Earl don't understand that. They think it's personal. We've got to have loyalty."

"Next blade he breaks, let him go."

Down in the cutting room, Earl saw the piece of nickel pyrite. Half the size of his thumb, embedded in the slab like a walnut, it flew down the track toward the saw. By the time his hand hit the switch, the nickel splintered with a bang. The saw seemed to spin backward as it slowed and stopped, three teeth broken off and two more bent sideways.

Earl was very late coming home that night. He stopped by White's house after dark, on the hill above his rented shack, and paid White the ten dollars he owed him. White took the money anxiously. Time for another case of whiskey, thought Earl. Then he went home.

"What happened? I was worried half to death."

"Oh, I've been clear to Lovingston and back," Earl said. "Fired for good this time."

"Have you been drinking? I smell bourbon."

"I was just up to White's. No, I didn't drink. He's rolling on the floor with the bottles up there."

"What were you doing in Lovingston?"

"I've gone on relief, Edie. I'm reporting for work in the morning."

"What work?"

"The CCC. Tomorrow the truck takes me away."

"Truck, Earl? Do you have to do that?"

"Yes, I'm going away. That's what I have to do. I'll be gone for a few weeks. They'll send you the money. Then I'll come back, and then I'll be gone again, I reckon. The work's up way the hell away from this place. It's up in the mountains somewhere. So I'll be living in a CCC camp until things get better. It's the best I could do."

She felt angry, but there was no point to letting it out. She could tell Earl was angry too, but he wasn't letting it out either.

That night they could hear bottles breaking up the hill at White's. "Lord, that man will drink himself to death," Edie said.

The morning was cold. Earl packed his clothes. Before he left, the kids showed him the trap-lines they were stringing along the riverbank for catching muskrats, rabbits, and birds.

"Work them good," Earl said. "Every day. This isn't for sport. You're going to need those rabbits and those muskrat hides."

They promised they would.

That night Edie felt very alone, with just the kids and the radio for company. "Gangbusters" blared out of the speakers in a rattle of cellophane machine-gun fire and Irish brogue mixed with the lingo of the G-man and the mobster.

"Did Daddy do something wrong? Is that why he had to go away?"

"No, he didn't do anything wrong. He went away to get work, and he'll come back again when he can."

She knew the children didn't understand things. She wasn't sure she understood either. Her husband had built a house with his own hands, and somehow that act was destroying them all. It had even driven Earl away from here, as sudden as death. Earl's leaving was a shock, like a broken promise, and left her hurting inside. She did not want to have to manage her family alone.

When the radio program ended, her second-oldest looked up at her with shining eyes. "I want to be like Machine-Gun Kelly when I grow up," he said. "Then we'd be rich, and wouldn't have to kill rabbits for supper."

"You do and I'll whip the hide right off of you. You're going to be an honest man."

"Ma, I was just pulling your leg."

"I'll throw the noisebox in the creek if it gives you ideas like that. I want Earl to be proud of you when he comes home."

Tags

Gary D. Mawyer

Gary Mawyer, a graduate of the University of Virginia creative writing program, is a faculty research assistant in the Department of Urology at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. (1985)