This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 1, "The Chords That Bind." Find more from that issue here.

A freight train rumbling across a nearby trestle; dogs lolling in grassy spots of shade; the last of summer crickets chorusing in trees whose leaves are wilted and ready to turn; a small boy circling silently, around and around, on a blue bicycle. Against this Faulkneresque backdrop, the busy clattering of an electric typewriter wafts out of the upstairs window of a neat white house in Nashville.

I happened to catch Anne Romaine, director of the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project (SFCRP), in the middle of typing some last-minute letters to advertisers for Tennessee Grassroots Days. I came on this bright September morning to help hang posters advertising the tenth annual Tennessee Grassroots Days, a two-day festival of traditional music and folklife demonstrations that is only two weeks away. But I also came to Anne Romaine's house for quite another reason: to talk history.

The tenth anniversary of Tennessee Grassroots Days is an important milestone. But the parent organization of the festival, the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project, in 1985 celebrated its twentieth anniversary. During the past two decades the SFCRP has touched the lives of thousands of Southerners, native and transplanted alike. Festivals, concerts, workshops, school and prison tours, and a syndicated television series are just a few of the SFCRP programs that have enabled audiences to see and get to know traditional artists and musicians. For 20 years, the project has upheld the ideals of presenting and interpreting the culture of black and white working people and introducing traditional folkways to a variety of audiences.

The Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project began as a fundraising vehicle for the Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC). According to Sue Thrasher, SSOC's former executive secretary, "SSOC was established by and for white students involved in civil rights work, to help them meet the challenges and confront the problems of being whites involved in a primarily black movement." The organization received recognition and support from black leaders such as Bob Moses and Stokely Carmichael. At a SSOC conference held at the Tennessee-based Highlander Center in 1965, staff members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) suggested that SSOC consider raising funds through a tour by Northern folksingers. One SSOC staffer was particularly interested in the idea and agreed to work on organizing such a tour. She was Anne Romaine, a musician and singer from Gastonia, North Carolina, then married to SSOC's chair Howard Romaine. So the Romaines traveled to New York to consult with folksinger Gil Turner, who in turn suggested that Anne meet with Bernice Reagon, a young black SNCC freedom singer who was living in Atlanta.

Anne vividly recalls her first meeting with Reagon, which strongly affected the direction of her efforts: "I remember sitting with Bernice in her wonderful kitchen, surrounded by cast iron pots and memorabilia from her many singing trips. During that meeting, Bernice and I realized that we were both vitally interested in the history of the South. I was primarily interested in the white working class, and Bernice in black culture. She liked our idea for a tour, but she felt it should not be just white, Northern folksingers. She suggested, instead, that we do a tour of both black and white Southern community-based musicians and singers."

In recalling their early work together, Bernice Reagon stresses that she and Romaine were both products of the civil rights movement, of black and white Southern communities, and that both — by virtue of their backgrounds — were extremely aware of music and culture in the shaping of attitudes and principles. In the introduction to her book, Oh, What a Time, Reagon wrote, "We were high on idealism, thinking that by using songs that had jumped cultural, racial, social, and economic boundaries, we could entice audiences to see where the songs and cultures had gone."

Reagon agreed to work with Romaine on planning a tour, with Reagon suggesting artists and Romaine booking them. The two decided that the tour should travel primarily to college campuses and should consist of a core of musicians who would perform every engagement, with special and local artists joining the group for one or two concerts. After months of organizing, they launched the first Southern Folk Festival tour in the spring of 1966. It lasted a month and featured Reverend Pearly Brown, black activist and singer Mable Hillary, Appalachian folksinger Hedy West, and New York singer/songwriter Gil Turner. Other performers — such as Pete Seeger, topical singer Len Chandler, and urban folksinger Carolyn Hester — joined the tour for several concerts. Romaine and Reagon emceed each performance.

What made the Southern Folk Festival special was its format. Romaine and Reagon planned each concert carefully as a "round-robin" performance that evoked the history of the South through song. Romaine explains, "Bernice would meet with each of the artists ahead of time to talk about their lives and repertoires. Together they would decide which songs to present." Reagon introduced each performer, setting the scene with background about his or her material and style. Reagon recalls, "On our programs, the older songs always came first: songs of slavery, church songs, hymns, and spirituals on both sides, blues, songs of labor organizing efforts, and [we ended] the program with songs of the '60s."

Although most participants felt that this format was effective, some artists chafed against it, feeling that Romaine and Reagon should allow them to perform their material without historical interpretation. One dissenter was Gil Turner, who had been very helpful in launching the project. He eventually left the tour over this difference in philosophy.

The tours had not been without political and racial incident, however. For a 1966 Southern Folk Festival concert at Vanderbilt University in which Pete Seeger participated, he and Romaine had agreed that he would be billed equally with other performers, with no special publicity. Despite this agreement, Romaine recalls, "When we arrived on campus, there were groups of people with huge signs, handing out leaflets with Pete's name all over them. I came on really strong to them, saying, 'We specified no special publicity for Pete!' Then I looked more closely at the leaflets. They were anti-Pete Seeger tracts published by the John Birch Society!"

Tour performers also were often confronted by bigotry and strained race relations from outsiders. Black and white musicians traveling, performing, eating, and socializing together often offended restaurant owners and community residents, resulting in confrontations. Romaine recalls the time a white sheriff seized the podium during a performance and began telling the audience he was the one looking after their best interests, not Romaine and her tour. And singer Hazel Dickens describes an incident when Romaine's van, full of black and white tour performers, was nearly run off the road: "We were going highway speed on the interstate and behind us came a bunch of white guys, running up against us, bumper-to-bumper. It was one of those truly terrifying moments when you wonder what the outcome is going to be."

Gathering the courage to live with fear of racial violence was necessary. Romaine says, "Reverend [Pearly] Brown, who was blind, was so strong and clear about his life. One night early on, because I was white, I was afraid to be seen driving alone in the car with him through Arkansas. Bernice picked up on my fear, and right there in the parking lot in front of everyone, she yelled, 'Romaine! You need to decide what's more important: your values, or what might happen. You can't live your life being afraid!' I was as mad as a hornet that Bernice had said that in front of everyone, and I snorted and fumed all the way through Arkansas that night. But I later realized she was right."

Bernice Reagon commented on tour race relations in Oh, What a Time: "The performers we selected had to be willing to travel by car throughout the South in mixed groups and, on stage, in concert, to acknowledge a common ground where it had never been acknowledged before. There was enthusiasm as well as fear from many of the older, traditional performers. Both were well-founded. The concerts, at black and white college campuses — primarily segregated in those days — at churches, at community centers, were affirming. People seemed very willing to consider the musical statement of humanism, of the quality of life. Our cars were also sometimes attacked, as in Jackson, Mississippi, where there was an attempt to push us off the road."

Romaine considered the 1966 Southern Folk Festival tour a resounding success. The bookings were good, the artists worked well together, and the unique concert format engaged and delighted. The performers traveled from engagement to engagement "caravan" style. The schedule was grueling but morale was high. The camaraderie of traveling, performing, and relaxing with each other at the end of a long day on the road fostered a family feeling that the artists conveyed while onstage. Although the money this first tour raised was modest, it was the beginning of the Southern Folk Festival as an ongoing organization.

The summer of 1966 was a turning point. Romaine recalls: "Howard and I were living in Swannanoa, North Carolina, working on an SSOC retreat center. I did a lot of singing myself, worked in an electronics factory, and got to know traditional musicians of the area. It was an environment filled with music and rich with folkways, and more and more, I knew I wanted to present this culture to a broader audience. For Howard, I think that summer was an unwelcome interruption in our civil rights work. But for me it was an expansion of my civil rights-oriented cultural work."

That fall, Romaine and Reagon began work on a 1967 Southern Folk Festival, this time planning a longer tour featuring more performers. Both realized that this project that had begun simply as a funding vehicle for SSOC had far greater potential. After lengthy deliberation the two decided that new performers should be enlisted, whose material embodied social issues beyond the civil rights movement, such as workers' rights, environmental concerns, and the anti-war movement. Most important, they decided that it was time for the Southern Folk Festival to become its own organization.

Sue Thrasher recalled the split from SSOC as amicable but inevitable: "As I remember, Anne's tour had always been a fairly independent project, and her interest was music. It made sense that the tour eventually became a separate entity."

Once Romaine and Reagon decided to leave SSOC, they embarked on serious fundraising. Several early trips to foundations sympathetic to the civil rights movement yielded nothing. Romaine noted, "None of them were particularly interested in a cultural program like ours, even though it focused on social issues."

Meanwhile, with the Black Power movement in full swing, Reagon began to devote more energy and leadership to black organizations and curtailed her direct involvement with the Southern Folk Festival. She did, however, remain a supportive adviser, strongly encouraging Romaine to continue her multicultural work. Reagon also backed Romaine's idea of adding a new component: a second tour that would feature primarily rural musicians, most of whom were white.

With help from old-time musician and collector Mike Seeger, Hedy West and others, Romaine developed a second tour she named the Appalachian Music Tour. Traveling for the first time in the fall of 1967, the new tour featured performers of all ages, representing a multitude of playing styles: singers Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard, old-time banjo player Dock Boggs, harmonica and guitar player Red Parham, dulcimer players Bill and Jean Davis, the Blue Ridge Mountain Dancers, and "Freight Train" composer Elizabeth Cotton.

Hazel Dickens recalls, "Except for the occasional folk festival, there was a real lack of stages for traditional performers in those days. The tour gave old-time and mountain musicians a chance to share their music with a larger audience. And the workshop format of tour concerts was, for me, a different experience. All of us sitting in a semi-circle onstage, interacting with and supporting each other — it really encouraged me with my own performing and songwriting."

Humor and a willingness to poke fun at the tour's shoestring budget style helped enable performers to live under stringent conditions. Romaine laughingly recounts how Hazel Dickens once returned her tour contract to Romaine. Attached to the space in which performers could indicate special needs was a list she had written in purple ink on pink toilet tissue requesting the following amenities: a private room; room service and breakfast in bed, including the waiter (twice on Sundays); top billing in large capital letters; and a seat in center stage in a red velvet rocker. The list was signed, "Her Excellency Lady Hazel."

In 1968 after completing two separate tours through all 13 Southern states, Romaine began looking for ways to bring traditional music to Atlanta, where she had moved. With funds from the federal Title III program and the Newport Folk Foundation, she developed a multicultural music series for the Atlanta public schools. Though the school system initially supported the program, Romaine remembers, school officials eventually grew uncomfortable with what they felt was inappropriate social commentary in the material presented. "We wanted to present music and history in a way that would connect with the students' lives," she explains. "The school administrators, on the other hand, wanted us just to present nice old-timey hoedowns and spirituals."

By 1968 the Southern Folk Festival tours had become much less overtly political, although they still built on their civil rights heritage. "One of my keenest, most bittersweet memories was the night Martin Luther King died," Romaine recalls. "We were at Alice Lloyd College in Pippa Passes, Kentucky. Bessie Jones and Jean Ritchie were on tour with us. It was an incredibly somber moment. I remember Bessie just shaking her head and saying, 'This is the beginning of the end.' On the day of his funeral, we were at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, and we dedicated our concert to King and his history."

As the tours became less blatantly political, they began presenting a broad spectrum of traditional performers. Now tour concerts often were sponsored by university student unions rather than by on- or off-campus political organizations and civil rights groups. Romaine saw the political pullback as a sign of the times.

By 1970 Romaine's commitment to social change and musical diversity had solidified. She had completed her master's degree in history. Reagon, who remained an adviser to the project, had begun graduate work in history at Howard University while working part-time at the Smithsonian Institution. Increasingly the two saw the tours as a musical forum for teaching audiences about the history and culture of the South.

Both Romaine and Reagon knew that any growth or expansion of the project would depend on securing outside funds to augment the money earned by the two tours. With the help of Marie Cirillo, head of an organization of former nuns called the Federation of Communities in Service, Romaine and the Southern Folk Festival won their first grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. "It was 1972, and I remember the day that first check arrived from the U.S. Treasury," Romaine remembers. "It was a real change in consciousness for me. Here I'd gone along for so many years in a mindset that wasn't real comfortable with FBI agents. Now here the [federal] government was funding our project." She also got the tours established as tax-exempt, in order to enable them to qualify for more types of grants.

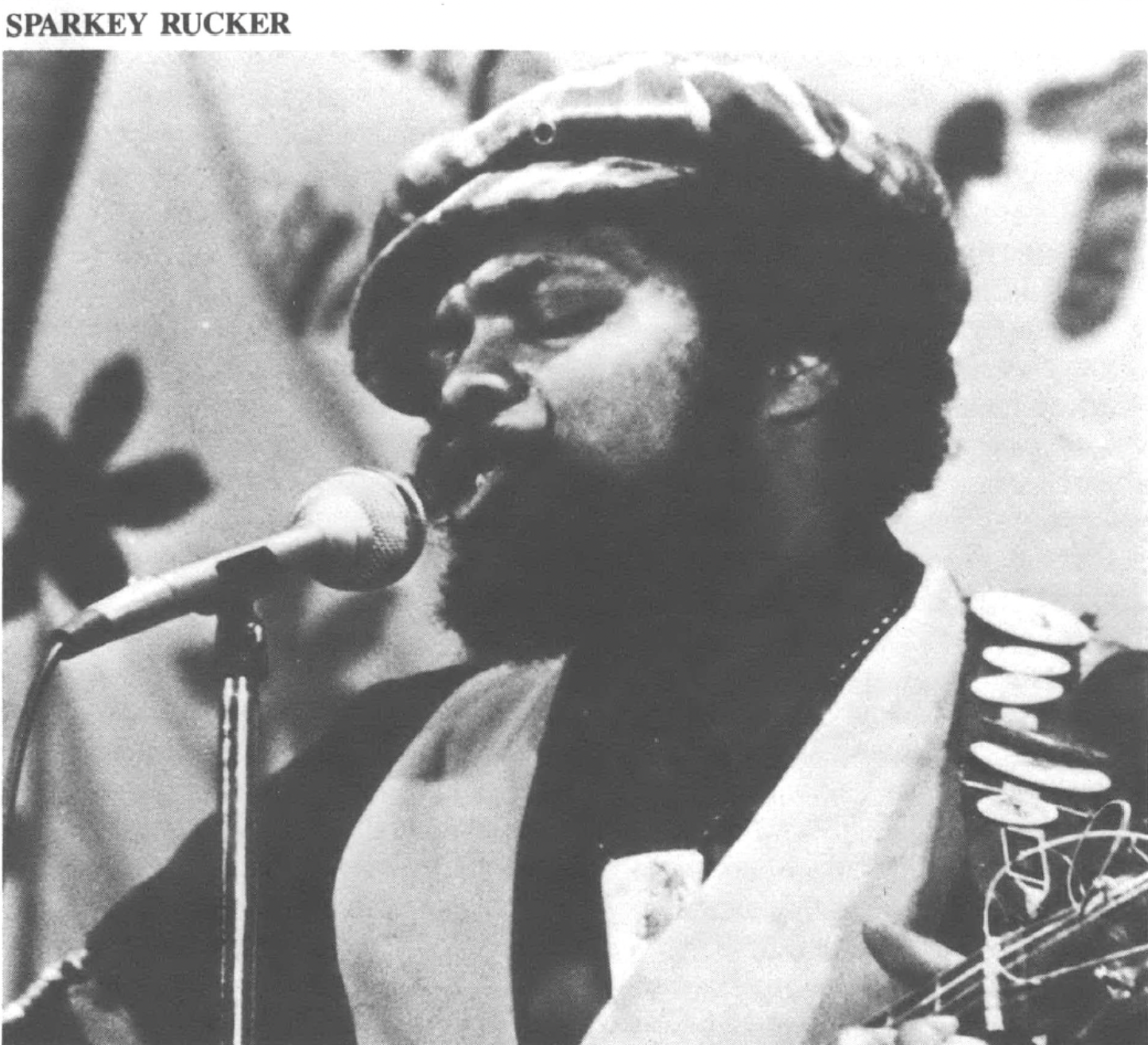

To this end, she established a board of directors consisting of artists and supporters such as Mike Seeger, Hazel Dickens, Alice Gerrard, Mable Hillary, Dewey Balfa, Sparkey Rucker, and Reagon. The board brought the separate tours and projects together under a new organizational umbrella called the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project.

During the next few years the SFRCP broadened its base considerably, sponsoring prison concert tours and public school programs in Georgia and Louisiana. In 1975 the city of Atlanta asked Romaine to direct a folk festival in its historic commercial district, Underground Atlanta. A large-scale festival was a new undertaking for Romaine, but with advice and encouragement from Bernice Reagon she produced an impressive event. "It was huge!" Romaine exclaims. "We had hundreds of performers and three stages: one each for traditional, transitional, and contemporary performers. We featured black and white musicians, singers, dancers, and even poets. It made me want to organize festivals for our organization on a regular basis."

Meanwhile, Romaine also had honed her own musical talents and hoped to perform and write songs more seriously herself. "I had a new record out on Rounder, had gotten into performing and writing contemporary country music, and had begun a band called 'Anne Romaine and the Honky Tonk Angels' that performed six nights a week at a place in Atlanta called Al's Corral. I was ready to do something about my own musical career."

During this period Anne and Howard Romaine underwent an amicable divorce. Fueled by her artistic aspirations and good memories of living in Nashville briefly during the '60s, Anne Romaine moved to Nashville in 1975, with her six-year-old daughter Rita. While working on her own career in music, she saw to it that the SFRCP board met regularly, and the organization continued to grow in scope, size, and reputation. It continued to sponsor fall and spring tours, which together were renamed the Southern Grassroots Music Tours, with Romaine and many volunteers doing the work.

An informal, interpretive workshop format is still the trademark of SFRCP tour concerts. Performers begin each concert with an upbeat number, sung while filing onstage to take their seats arranged in a semicircle, where they await their turns to perform. The concerts always end with musicians grouped around several microphones, leading spirited singalongs. Repertoires and styles have evolved since the tours' early days, but younger artists and new songs seem to fit well alongside the old and traditional. With the background and interpretation provided by Romaine and other emcees, audiences welcome the diversity and contrasts in songs and singers. Hazel Dickens comments, "We almost always had a good reception. Depending on where we were, most students seemed to have a handle on what it was we were trying to say with our music. Most times we would do smaller workshops before the concerts, which would give people a chance to come and hear us talk about our music and ask questions."

Ronnie Geer, coordinator of student activities at the University of Alabama, describes his perception of the audience/performer relationship at tour concerts: "The performers involved the audience in the show from the very beginning. The audience promptly took the performers to heart, probably because both the music and the people of the Southern Grassroots Music Tours were so real. The spontaneity of the evenings gave the feeling of a large, festive family reunion."

In early 1976 Tennessee state folklorist Linda White asked Romaine if she would direct a festival of traditional performers in Nashville's Centennial Park. "Of course I said yes, and the first annual Tennessee Grassroots Days became a reality," says Romaine. "We had $2,000 in Tennessee Arts Commission funds and the program only lasted one day. We only had one stage and it was a freezing cold October day. But it was a fantastic program."

Tennessee Grassroots Days continues as an annual event. Each year a special staff and group of advisers composed of Tennessee-based folklorists, business leaders, arts supporters, and performers work with Romaine to plan, promote, and raise funds for the festival.

In 1981, Tennessee Grassroots Days received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Tennessee Committee for the Humanities, enabling field workers, folklorists, and historians to participate as interpreters and emcees in a much-expanded festival. In other years, with only the cash raised from program book ad sales and funds from organizations such as the We Shall Overcome Fund and the Tennessee Arts Commission, the festival has been a more modest, intimate event.

Regardless of available funds, the two-day festival consistently presents a comprehensive array of musicians, ranging from 90-year-old former coal miner and ballad singer Nimrod Workman to charismatic bluesman and folksinger Sparkey Rucker; from popular bluegrass superstar Peter Rowan to veteran black gospel singers The Fairfield Four; from Southern songwriter Guy Clark to the old-timey Roan Mountain Hilltoppers. With or without grants, the festival features a broad sampling of folklife demonstrators, including artisans such as gourd-carver Dorothy Bumpas, knife-honer Adam Turtle, marble-maker Bud Garrett, and the Jolly Dozen quilters.

Every year thousands of Tennesseans fill Centennial Park, wandering between the music stages set at opposite ends of the festival site, observing and talking to folklife demonstrators, and consuming great quantities of downhome cooking.

Tennessee Grassroots Days participants are extremely loyal. Scores of the state's traditional artisans and musicians show up each year to take part in the festival, supported by many volunteers who emcee, run information tables, act as stage managers, set up the festival, and clean up afterward. The venerable singer Memphis Ma Rainer came every year until she died, even though it meant a difficult drive from West Tennessee and two days performing in the early fall heat. Grand Ole Opry favorite Wilma Lee Cooper regularly fits several Grassroots Days sets around her Opry commitments, and long-time Opry announcer Grant Turner shows up annually to emcee.

Project adviser and emcee Tommy Lewis explains the importance of Grassroots Days to Tennessee: "The festival is like a giant melting pot and a means of showing people not just what went on in the old days, but what traditional things are still going on today. People who may not have direct, everyday contact with beekeeping or down home cooking or four-part traditional gospel can learn about it at Grassroots Days. And the generational element is important. When I bring a youth choir to perform, or when Robert Spicer and Jackie Christian invite kids up on stage to learn buckdancing, and parents and grandparents watch, it involves all ages in learning about traditions, not just the old or the young. That's what makes Grassroots Days different from most other cultural events in Tennessee."

Despite dwindling financial resources, Romaine continues to run Southern Grassroots Music Tours and Tennessee Grassroots Days. Alice Gerrard comments on the impact of the chronic lack of funds has had on the SFCRP: "Having to operate on a shoestring creates certain problems; ones that any organization must really work at to get around. Anne and the project have always had to live with a shortage of funds, which has a way of limiting what you do, how many new performers you enlist, and even the ways in which you deal with committed artists and performers. Anne's done a remarkable job, but I'd like to see the SFCRP reach out to embrace new ideas and a wider variety of performers, and I'd especially like to see Anne involve others in managing various project activities. All these things require money."

Romaine believes that the organization will continue and says that she, too, sees a need for new leadership blood: "We're the only organization in the United States that sponsors regular tours and festivals of traditional Southern musicians and artists. That in itself is significant. Eventually I hope to bring into the organization some young, talented, and enthusiastic administrators, easing myself into an advisory role."

Romaine also recognizes the need for SFCRP to embrace more current social issues. She recalls one afternoon two years ago when songwriter and Grassroots Days supporter John D. Loudermilk delivered a brief but riveting challenge to the festival's advisory committee. "He reminded us that we were no longer in the 1960s, in the heat of the civil rights movement, but were instead in the '80s, when nuclear arms, child and spouse abuse, environmental pollution, and drug abuse were issues of the day. John was calling for our organization's activities and goals to begin reflecting that."

Romaine says that the SFCRP is just beginning to meet these new challenges. "We'll always be an organization whose roots are in the civil rights movement of the '60s. If it weren't for civil rights, we never would have existed. But if it weren't for the broader folkloristic and musical views put forth by our advisers, and the challenges put forth by supporters like John, we never would have lasted."

As long as there are traditional Southern musicians and artisans to share their gifts, political and social visionaries to offer advice, and willing volunteers to haul equipment, strike stages, and wield staple guns, there will most certainly be a Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project. And, most likely, as long as there is a Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project, somewhere there will be Anne Romaine — laboring, planning, organizing, cajoling, economizing, persuading, guiding, and laughing her hearty, infectious laugh.

Tags

Patricia A. Hall

Patricia A. Hall is a folklorist and writer in Franklin, Tennessee who sometimes emcees at Tennessee Grassroots Day. (1986)