This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 1, "The Chords That Bind." Find more from that issue here.

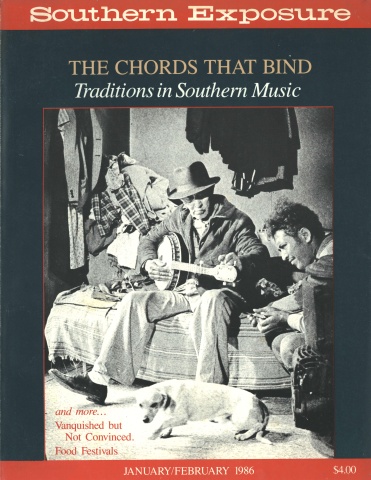

Bascom Lamar Lunsford was an Appalachian original. Born in 1882 in Mars Hill in Madison County, North Carolina, which he called "the last stand of the natural people," he was hooked early on traditional lore. After attending Rutherford College, he worked as a school teacher, nursery salesman, bee and honey promoter, supervisor of boys at a school for the deaf, student, practicing lawyer, county solicitor, college teacher, newspaper editor, war bond salesman, Justice Department agent, newspaper publisher, church field secretary, New Deal programs worker, reading clerk of the North Carolina House of Representatives, performing artist, collector, and festival promoter. These jobs may seem diverse, but the unifying thread was a consuming interest in the folk traditions of North Carolina and the Appalachian mountains. He used each job to further his knowledge of people and their traditions.

Lunsford was born into a family of teachers and was thus part of the mountain middle-class of his time. Through jobs and activities, he became intimately acquainted with most aspects of traditional Appalachian life. His diverse background enabled him to win the cooperation of well-to-do and powerful people as well as those who were the carriers of tradition. Most of his energies during his long life went into promoting the folk tradition of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. He died in Asheville, North Carolina in 1973 at the age of 91.

The following excerpts come from a recently recovered notebook of Bascom Lamar Lunsford. Emmett Peter, Jr., a writer from Leesburg, Florida, discovered this typescript in an Asheville thrift shop and bought it for 25 cents. Apparently it is a notebook lost during the 1950s in the mail between Lunsford and graduate student Anne Beard, who was then working on a thesis on Lunsford. This particular piece is an introduction Lunsford wrote in 1934 for a proposed book of songs he had collected.

Lunsford is best remembered for his Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville, which he started in 1928 and which continues to this day. The first festival of its kind, it served as a model for other events, including the National Folk Festival, now produced by the National Council on Traditional Arts in Washington. The festival, sponsored by the Asheville Chamber of Commerce, was Lunsford's means of calling attention to the traditional arts of the mountains and promoting a positive image of mountain people to refute the popular stereotypes.

Lunsford recorded his "memory collection" of some 320 songs, tunes, and stories for Columbia University in 1935 and the Library of Congress in 1949. These collections plus other material make the Lunsford collection at the Library of Congress the largest contribution by a single performer. Lunsford's personal files hold over 3,000 songs, tunes, and variants.

Lunsford and Lamar Stringfield — a distinguished classical musician, composer, and founder of the North Carolina Symphony Orchestra — collaborated on a book published by Carl Fischer in 1929, 30 and 1 Folk Songs from the Southern Mountains. No doubt Lunsford wanted to publish a larger volume of his collected material, and prepared the following essay as the introduction. The material had been typed in the size and format of Lunsford's lost notebooks. The first page of the manuscript is missing, and so the first part of the beginning paragraph, by Lunsford, is taken from Anne Beard's thesis, "The Personal Folk Song Collection of Bascom Lamar Lunsford" (Miami University, 1959).

Perhaps somewhere the remaining notebooks are languishing under coats of dust to be discovered by a knowing and inquisitive collector. We hope that if they are found they will be added to the extensive Lunsford materials in the Mars Hill College Library.

— Loyal Jones

I vividly recall when a lad of seven years, riding behind my father on our faithful family horse, Charlie, the distance of 40 miles from our home on Hanlon Mountain in Buncombe County to visit my great-uncle, Osborne Deaver, who lives at the Forks of Ivy in Madison County, near Mars Hill College, the place of my birth. I had looked forward to this trip for many days because Uncle Osborne was a great fiddler of the old school. I had often heard my mother, his niece, sing and hum many of the songs she learned in her youth, some of which she stated were Uncle's fiddle tunes. So one can imagine my deep interest when at my journey's end I was able to see my aged uncle take his precious violin from the black wooden case which he always kept under his bedside, draw the bow across the catgut, and glide sweetly into some of the old favorites I could recognize.

The next step in this development naturally was the collaboration between my brother and me in the making of a series of cigar-box fiddles and the playing together some of the simplest tunes we knew. After a few public performances at the old "field school exhibitions," Brother provided a banjo. The banjo brings out the balladry in my system, so at an early age I was a full-fledged ballad singer of the Southern Appalachian type. Whereupon, I began the erection of a musical layercake with work and school as a filling with such social ingredients as "bean-stringin's," "butter-stirrin's," "apple peelin's," "tobacco-curin's," "candy breakin's," "candy pullin's," " 'lasses makin's," "corn shuckin's," "log rollin's," "quiltin's," "house raisin's," "serenades," "square dances," "shoe arounds," "shindigs," "frolics," "country weddings," and "school entertainments."

These contacts brought about the exchange of "song ballets" between the young people with whom I mingled, and up to this time I had only tried to remember such songs and tunes as especially appealed to me or such as I could use in time for entertainment purposes, so naturally the older ballads, being more difficult to render, I neglected to acquire. At this late date, I can realize how much good material I must have let slip away from me then. A song collector can realize how often and sorely disappointed I am to find the trail a cold one and the former singer merely a memory in the community. The mountain counties of Buncombe, Madison, Haywood, and Henderson in North Carolina embrace the extent of my range at that early period.

In summer and fall of 1902, with a second grade certificate I took a [job teaching at a] public school at Cross Rock near the now famous Doggett Gap in Madison County. I began at this time to realize something of the literary value of these ditties, but I learned more songs only to play and sing them myself. Week-end trips and an occasional party during the term provided opportunity for this. To give a picture of how this would promote a further interest in the folk life of this section, I mention a trip Bill Payne and I took when we walked across the mountain to Little Pine Creek where he talked up a party for Saturday night. The Brown girls and the Farmer girls were to be there, and Uncle Dolf Payne, with his long beard and black cap, riding a small rat-tail mule, came in early. His saddlebags indicated he would be in a good humor. This proved to be an all-night session with "candy breakin," fiddling, ballad singing, and dancing.

A change of vocation after the close of my school to that of canvassing in various mountain counties representing a nursery company brought me in close contact with rural folk and extended my territory again, and then it was I was able to cover to a great extent the counties of western North Carolina and to dip into the adjoining states of Tennessee, Georgia, and South Carolina. Songs from the valleys of Cheoh and Stecoah in Graham, where Miss Lela Ammons and others sang, were added to my collection. [I collected] "Old Stepstone," "Old Garden Gate," and numerous others at the old-fashioned home of sheriff John Ammons on Mountain Creek. A most hospitable atmosphere prevailed and on each week-end for many months the social pastimes of a happy highland people impressed me deeply. Their true worth to me was expressed in their songs, which ran the range from childish riddles to ballads and sacred songs. From the valleys of the beautiful Hiawassee in north Georgia, and Clay and Cherokee Counties in North Carolina, and from the communities of Gum Log, Hightower, Shooting Creek, Tusquittee, and Bear Meat, I acquired other songs, and especially recall Miss Ada Green, now Mrs. Sampson, singing "Row Us Over the Tide," "Lula Wall," and "Dying Girl's Message."

Macon County, North Carolina and Rabun County, Georgia are both alike in folk traditions. I recall many occasions in that section. The "Zackery Old Place," now almost covered by a lake on the Little Tennessee River, was the scene of many happy social pastimes. Hal, a young man then, and his two sisters, Ruth and Agnes, were all contributors to my store of songs. A singing at Sam Higdon's on Ellijay near the home of Jim Corbin the noted banjo player, or a square dance at Bascom Pickelsimer's on Tesentee, and like events or diversions tended to keep me satisfied in the field as a nursery salesman. I recall an occasion in Rabun County, Georgia, when I spent the night at the home of Ed Lovell. A fellow sojourner by the name of Brown entertained us during the evening by singing "Lord Lovel." Probably the name of our host brought the old song to mind. I think it true that the picturesque country lying between the Brasstown Bald in Townes County, Georgia and Pilot Mountain in Surrey County, North Carolina, a distance of about 300 miles and extending northwestward beyond the Great Smoky Mountain range, comprises the most important pocket in America for the preservation of folk songs and folk customs.

I attended dances on Mills River near the Pink Beds where Rack Kimsey and Bob Reed did the calling. The Posey girls and Ella Warlick, splendid square dancers, were there, and the Posey boys sang and played this little couplet:

Shout, little Lula, shout your best,

Your old grandma's gone to rest.

I saw that catfish a-comin' up the stream,

And I asked that catfish, "What you mean?"

I caught that catfish by the snout, And I turned that catfish wrong side out.

I heard some words to "Italy" on Sugarloaf Mountain, and [here] Ebe Davis first sang [for me] "Goin' Back to Georgia" and Anderson Williams sang his "Mr. Garfield" and Miss Queen Justus taught me "Bonnie Blue Eyes." "The Weeping Willow Tree" was added to my collection here, along with many others. These contacts were not only a source of great pleasure then, but as time went by they have broadened my sympathies and enabled me to enter into the various social pastimes of "mine own people" free from affectation, and I have no desire to ever get out of common touch with the ballad-singer; and such a course often proves to me its worth.

"A change of venue" with a program similar to that pursued along the Blue Ridge and Great Smokies brought me to the beautiful Brushy Mountain section of North Carolina, my first acquaintanceship being made around Little Mountain, and in Union Grove, New Hope, and Olin Townships in the county of Iredell. Dodge Weatherman, a Baptist preacher and one of the best old-time singers, was alive and in his vigor. I made my home with them for quite a while, and attended every sort of gathering, from "protracted meetings," funerals, weddings, baptizings to country picnics and parties where the attendance was less and the fiddle and banjo and ballad-singer would come into their own. Preacher Weatherman was a kindred spirit and often requested me to aid him in what way I could at weddings, funerals, and gatherings when he needed a handy man to serve in a kind of "pinch-hitter" capacity.

I had walked one evening through the old-fashioned covered bridge near the home of Nels Summers some distance from Olin, and after finding his family had quite a number of stringed instruments I asked for a night's lodgings, with the view of making a sale, of course. Summers was a "good liver," "had plenty about his house." Especially do I remember "Cack" and "Hum," two girls who sang songs of the popular variety. However, in modern-day parlance, my songs "seemed to go over." Next morning Summers bought some cherry trees and when I asked my bill for lodging he said, "All I want is for you to get the banjo and play 'Mole in the Ground' one more time." I learned this song from Fred Moody in Haywood County. It was in the Vashti section, where the people of the countryside were filled with superstitious consternation, when during a terrible storm, about an acre of earth and rock on Sugarloaf Mountain (not the mountain of the same name in Henderson County) sank some several feet. Some thought it an ill omen, while others considered it more lightly, and even sang,

If I was a mole in the ground,

I'd root old Sugarloaf down.

Elza Wooten, his sister, Miss Martin, and I attended a Negro Children's Day exercise near old Briar Creek church where I heard this beautiful spiritual for the first time:

Drinkin' of the wine, wine, wine;

Drinkin of the wine, holy wine;

You oughta been there four thousand years,

Drinkin ' of the wine.

It was customary for the agents to be called to the nursery early in autumn to prepare for delivery, and to get an object lesson in the growing and handling of nursery products, so for many weeks I was able to avail myself of the riches in the song-life and the country pastimes in Powell's Valley and along the Clinch River in east Tennessee, my interest in those things far exceeding my taste for tree-digging and "standard fumigation."

My work with the east Tennessee company closed in 1904, and 1905 found me back on Hanlon Mountain, but soon to enter upon a venture in honey culture with Mr. George I. Elmore, an extensive beekeeper who owned and worked bee yards in nearly a hundred locations in several counties, mostly in Buncombe and Madison counties, North Carolina. We traveled and worked together and often after a day's journey through the mountains the evening hours would find us seated at the cabin door of some mountaineer with the family gathered 'round, listening to the banjo or fiddle. The higher into the mountains, the better the pasturage for bees, and naturally most of the yards were located high up where the linn and the poplar bloom ensures a good crop; this also insured to me a good harvest in balladry. The very names of some of the localities are indicative of rustic life: Freezland, Spring Creek, Sandy Mush, Peep Eye, Sandy Bottoms, Brush Creek, Bear Creek, Trail Branch, most all of which have been scenes in time of the most joyous social gatherings at various mountain homes, where the rural fiddler, clogger, or singer would be the center of attraction.

The period following found me "filling the vacancy" of a teacher of English in Rutherford College. My work had given me more confidence in myself, whether this was well-founded or not, so I had arranged a discourse of more than an hour's length on no less a subject than "North Carolina Folklore Poetry and Song," and while I had slipped away a time or two to deliver it at schools where the teacher was kind enough to take the risk, I really gave it its initial test at Rutherford College. To my surprise and to the startling of the students and the "natives," it "went over." The parts of it pertinent to ballads and folk songs, the part I was on nettles about, such as singing with a banjo accompaniment "Swannanoa Tunnel" and "Free Little Bird" ("Lass of Rock Royal"), was the high spot of the program.

The "ballad country" has been greatly changed by the advent of good roads. The noted "Dark Corner" section of South Carolina where I learned the "Howard Song" and "John Kirby" and an old ballad "The Brown Girl" (Child No. 295), and many others, and a section with a considerable provincial reputation, of which its name indicates, is now traversed and fringed by good highways. The heretofore isolated mountain district of Big Laurel, Shelton Laurel, Sodom Laurel, and Spill Corn, which has contributed so richly through the Sheltons and Rices and other ballad-singing families to the precious collection of Campbell and Sharp [Cecil J. Sharp and Olive Dame Campbell, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians] has a magnificent highway winding through. The Roaring Fork, Bluff, Wolf Creek, and Shut-in communities in that range of mountains between Pigeon River on the south and west and the French Broad River on the north and east, and Hot Springs where a prominent citizen once ordered an auto shipped by rail, but could never get it out of the village for lack of a place to drive it, are now connected with roads and the citizens are real neighbors in the general sense of the term.

School entertainments and song collecting carried me far into these coves. It was at Roaring Fork where a typical discovery was made. While looking over a number of songs handed in for me, I noticed one written by a child of nine, with the title "Little Marget." Loretta Payne sang the old ballad she had heard her mother and grandmother sing.

Little Marget sitting in the high hall door,

Combin' back her long yellow hair;

She spied Sweet William and his new-made bride

Riding up the road so near.

Visiting a school community in the interest of this fascinating study, it's hard to say which affords one the greatest gratification, the securing of ballads you had anticipated finding or a discovery of one you had not counted on. I recently had this experience. I had made several visits to a family in an effort to have the father recall what he knew of "The Farmer's Curst Wife," of which I had no copy except those in published collections, and was successful in getting Miss Hettie Lane, the daughter who had contributed before to my collection, to copy a few fragmentary stanzas. Yet about this time, still proud of my effort, I was called to the Flat Creek community to direct a fiddler's contest. So imagine how elated I was when Jeter Metcalf of Bull Creek in Madison County won a prize for banjo solo using the old ballad, and a fine text at that, closing with

Seven little devils went scaling 'round the wall,

Saying, "Take her out, Dad, she's a-goin ' to kill us all."

Among the teachers of public schools and colleges, I recall but only two instances where a discordant note was sounded, out of the many hundreds of places I have visited during the last 15 years. One case was where I had offered a two-and-a-half dollar gold piece to the student who could bring in the best collection of ballads. The superintendent, who was not native to that section, asked if I was offering a "premium on ignorance." The other case was where I ran across a teacher in another state who was a native of Haywood County, North Carolina and was superintendent. He remarked that he knew more about the subject than I did, for he grew up in the mountain section and was trying to forget all he could of those old things.

Charging an admission at these school programs has enabled me to give to the schools an allowance, to frequently give a cash prize upon occasion for ballads, and to finance each trip and not infrequently to come home with money in my pocket. Almost without exception, the prizes which were awarded to the actual contributors would go to individuals whose family traditions were linked most interestingly with romance and were rich in the lore of the countryside. Miss Jeannette Lyda won a prize in this way at Fruitland Institute on Clear Creek in Henderson County. Her father, Bud Lyda, was an old wagoner, the genuine "wagoner lad" type. His fiddle and camping outfit has carried him into several states, and a visit to the Lyda home placed me in the most congenial atmosphere. It was here I got, indeed, "The Wagoner Lad," "I Was Brought Up in Conde," and "Only Three Grains of Corn, Mother."

In [my collection] are quite a number of songs of the ballad type [for] which the original author is unknown, or [which] are based upon some known tragedy, the circumstances of which can be established either from record or from oral tradition in the locality from whence they come, and they have passed into the traditional song-life of the Southern mountains, and have been transmitted in the same way and have undergone the same sort of change as the English and Scottish and other older ballads of this country.

To show this, the Naomi Wise tragedy is aptly illustrative. Randolph County, North Carolina, in 1803, was the scene of a heart-rending incident. The details have been published by state papers and some county papers. Deep River, which flows through that hill country in which the unfortunate Naomi was drowned by her false lover, turns thousands of spindles in a mill bearing her name. At the old ford where the road wound into the river in the older days, there is an expanse of rock-formation exposed where tradition has it the tracks of Lewis's horse and the barefoot track of poor Naomi may be seen. I was shown it by a youth of the neighborhood, and it does resemble strongly that sort of track. The ford is called the "Naomi Wise Ford." I went to New Salem, some miles from this place, and saw the "Adams Spring." I drank from this spring of pure, clear water and recall the story of how Naomi had kept her tryst here, where she used a stump for an "upping block," and had mounted behind him for her death ride upon the horse he had "won in the race." The old home where Naomi had lived with her foster parents had been removed and built into a barn, but I secured the old doorlatch that the unfortunate girl touched for the last time when she left on her doubtful journey.

In company with Miss Cox, the principal of the school, I went to the cemetery of Providence Church, near the school, where she showed me the grave said to be the grave of Naomi Wise. It had a small, unpolished natural stone marker, with the name Naomi Wise cut clearly on its face. She further said that she herself had, some several years previous to this, erected this marker but that the grave was known to be the grave of the unfortunate Naomi.

Though the tragedy occured in 1803, it is only in the last decade that the song "Naomi Wise," like many others, received any great publicity. Now some phonograph records have been made of it, with magazine stories as to its origin, some claiming authorship of the song as is the case often in anonymous composition. This leads me to this statement: I have lived to see a great awakening in folk productions along many lines and an increased interest with which it has been received.

When the noted collector, Robert W. Gordon, visited our section, I enjoyed the pleasure of having him with me on an intensive campaign for ballads for several weeks, which carried us through many counties in the state and into South Carolina. I recall our visit to Jackson County (N.C.) where I secured a splendid collection through the cooperation of Dean W.E. Bird, of Western North Carolina Teachers' College at Cullowhee. It was a revelation to him [Gordon] to learn of the many mountain communities in this section bearing such names as Canada, Italy, Egypt, Jericho, and Sodom. It was interesting when the little girl from Canada sang:

There was another ship

All on that sea,

And the name that they gave it

Was the Merry Golden Tree.

As it sailed on the lowland, lonesome, lonesome,

As it sailed on the lonesome sea.

Miss Dorothy Scarborough, who visited Asheville some three years ago, was deeply interested in the ballads and songs of the mountains, and I had the honor to act as sort of guide or scout in several short trips we made together in quest of songs. [Her collection of songs, A Song Catcher in the Southern Mountains, was published in 1937.] We visited the Ivy section, Beaverdam, Spooks Branch, and I brought into the city for her to interview several singers: Miss Selma Club from 'Tater Branch, who sang 18 or more songs for her; the Queen brothers from Toe River in Mitchell County, whose fiddle tunes and rollicking mountain songs were highly gratifying to Miss Scarborough; and the Cook sisters and Greer sisters from the valley of the New River in Watauga County were in the group. Miss Scarborough's words of encouragement about the merit of the preservation of these quaint things and her statement here to the press I highly appreciate.

It has been suggested that possibly ballad-making was a lost art, but those who have made this suggestion have lived to see others made and popularized. And the same may be said of many of the old tunes without lyrics and the games and dances of the Southern mountains. So deeply have these things become embedded in the background of this section that it is next to impossible to get away from it and so should not.

This is the reason that doubtless such programs as the [Mountain Dance and Folk Festival], the great outdoor program held at McCormick Field at Asheville, North Carolina, is a thing entirely practical here. [It has a] close proximity to both the participants and to those who love the songs and pastimes as a part of their life. This annual event, which is promoted by the Asheville Chamber of Commerce, has been established for seven years, and has increased in interest and popularity from year to year, and is a further proof of this "renaissance" in folk expression. So one can imagine the sense of responsibility I felt when I was called upon in the beginning to manage and direct this program which is always filled with so much of interest to me.

These programs are held in midsummer at the height of the tourist season, but the individual performers, about 300 in number, including the director, are mountaineers. Fiddlers, ballad singers, banjo players, harpists, guitarists, cloggers, yodelers, and many of the string bands are there to enter into the joys of the festival. Upon two evenings a contest is staged between eight or more dancing groups of eight couples to the group, which bring their home bands with them and dance the square or contra dance figures as danced by their fathers and mothers in the long ago. Judges are chosen for each evening for the bands as well as for the dancing groups and from those who are familiar with both the music and the figures of the dance.

It is a striking feature of these programs to see the number of families which constitute a string band of themselves, some of which have from time to time appeared on programs for me and the list of which is rather long: the Greer sisters of Deep Gap in Watauga County, who have been with me in school programs and in annual programs in Asheville; the Cook sisters of Rutherwood, also of that county, who have assisted me in the same way; the Burleson sisters of Mitchell County who have helped me in radiocasts; the Queen brothers from the North Toe River; the Callahan brothers; the Lovingood sisters; the Clinton sisters; the Kelly sisters; the Shope family; the Shelton brothers; the Childers string band; Manco Sneed's family; the Cole string band; the Carter string band; the Pressley string band; and others.

The most unusual thing is the great number of girl fiddlers to be found. In this respect, conditions have considerably changed. When I first began to note these things, there were very few. Now, quite a number deserve to be mentioned in this connection: Miss Maude Burleson, formerly of Spruce Pine in North Carolina but now of Akron, Ohio, is a prizewinner and an old-time fiddler, singer, and dancer, yet an attractive young woman. Her singing of "Red Apple Juice" or playing of "Devil's Dream" or "Walking in the Parlor" are hard to excel. Miss Mabel Cook of the New River Valley who plays "Ragged Ann," "Hen Cackle," and others is also a prizewinner and would make all the old-timers take notice and is only about 22 years old. Miss Minnie Greer, about 20, plays the fiddle, banjo, guitar, mandolin, sings, dances, and yodels, and so the story goes on. All of these young ladies are native to the mountains, are beautiful, and in their bearing show modesty and character.

So in this rambling introduction, I have endeavored to touch briefly upon every part of my life which one may see could bring me in contact with the people knowing the traditions, ballads, and music of my people from the time of my cross-country ride to the Forks of Ivy about the year 1890 to the present time. I have collected over 3,000 song texts, most of which are of some folk value. I desire to pass on the songs with the hope that [others] may derive a pleasure similar to the joy I have found in collecting this material first hand.

Leicester, North Carolina

January 19, 1934

Tags

Loyal Jones

Loyal Jones is the author of Minstrel of the Appalachians: The Story of Bascom Lamar Lunsford (Appalachian Consortium Press, 1984). He is the director of the Appalachian Center at Berea College, Berea, Kentucky. (1986)