Vanquished but Not Convinced: Worker Militancy and Vigilante Violence in Tampa

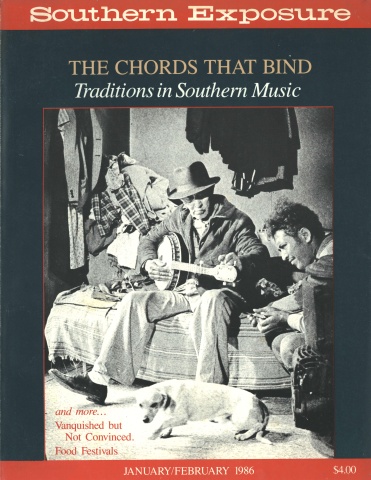

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 1, "The Chords That Bind." Find more from that issue here.

"The cigar industry is to this city what the iron industry is to Pittsburgh," the Tampa Tribune observed in 1896. The production of handmade cigars dominated Tampa's economy for 50 years after the first plant opened in 1886. Cigar manufacturers originally went to Tampa in search of labor peace which they equated with the absence of strikes or any other disruption of production by cigarworkers. Instead, the employers met a politically motivated and militant workforce.

Worker organization leading to strikes against the cigar industry began in 1887. In response, local businessmen and city professionals organized anti-labor vigilantes to combat the organization and demands of the workers with violence. Years of class war ensued until the government became the buffer between the workers and the industrialists, and the cigar industry began to wane.

Spanish cigar manufacturers had first fled Cuba in the 1860s when their cigar industry was disrupted by the Ten Years' War for Cuban independence. Driven from Cuba, a number of manufacturers were attracted to the United States by tariff laws which placed high duties on finished cigars but not on tobacco leaf. Seeking access to the North American market, immigrant capitalists found a haven in Key West, Florida, which was close to the necessary supplies of clear Havana tobacco and skilled labor. However, after the spread of unions and a wave of strikes in the 1880s, several Key West manufacturers relocated to Tampa, a city which provided cash subsidies and the promise of labor peace.

Vincente Martinez Ybor, the first cigar manufacturer to make the move, was lured by the Tampa Board of Trade. Organized by the community's business and professional elite in 1885, the board agreed to raise $4,000 to subsidize Martinez Ybor's purchase of a $9,000 tract of land just outside Tampa's city limit. Ybor quickly built a factory and housing for Cuban and Spanish cigarworkers who in 1886 began production of the fine, handmade cigars that put Tampa on the map. Ybor City, originally a separate municipality, was annexed by Tampa in 1887, but it remained until World War II a company town dominated by the cigar industry.

The production of cigars ignited a spectacular boom in Tampa. A sleepy town of 720 people in 1880, the city had almost 6,000 people ten years later. Tampa's growth was fueled by outside capital and immigrant labor that ultimately transformed the city into the world's largest producer of handrolled cigars made from imported clear Havana tobacco. By 1910 Tampa was turning out one million cigars a day, and its 10,000 cigarworkers represented over half the community's entire labor force.

Cigarworkers and their families made Tampa a vibrant, ethnically diverse community actively interested in politics and ideology. The immigrants who flocked to the city's cigar industry were at first Cuban and Spanish-born, but they were soon joined by a large number of Italians. In 1910, when almost half the city's population was first- or second-generation immigrants, the cigar industry's labor force was 41 percent Cuban, 23 percent Spanish, and 19 percent Italian.

The world of Tampa radicals was extensive and lively. Immigrants formed local clubs and discussion groups that were devoted to a wide array of socialist and anarchist causes. Meetings in places such as Ybor City's Italian Socialist Hall attracted large crowds who heard lectures by national and international luminaries such as Socialist Eugene Debs, Wobbly Bill Haywood, and Errico Malatesta, an anarchist exiled from Italy. Tampa's immigrant community also supported a number of radical newspapers that were published locally in Spanish, Italian, and English. Titles such as El International and La Voce Dello Shiavo ("The Voice of the Slave") accurately evoke the papers' orientation. The Tampa Citizen, published by local unions during and after World War I, announced on its masthead that it was "PUBLISHED IN THE INTEREST OF THE WORKING CLASS OF TAMPA." The local correspondent for a manufacturers' journal complained in 1919 that "the average cigarmaker here is well-posted and deeply impressed with the radical movement in the United States."

The best reflection of the sentiments of immigrant cigarworkers was the institution of the factory lector, or reader. Paid by the cigarmakers to read while they performed their silent handwork, the lector sat on an elevated platform and read material chosen by the workers who voted on what they should hear. The selections ranged from daily newspapers to European novels. The texts of both El Internacional and Les Miserables, for example, contained heavy doses of radical thought. As a former reader, Abelardo Gutierrez Diaz, later reminisced, "The lectura [reading] was itself a veritable system of education dealing with a variety of subjects, including politics, labor, literature, and international relations." Confirmation of this statement came from Tampa's leading anarchist, Alfonso Coniglio, who was a cigarmaker by the age of 14. "Oh, I cannot tell you how important [readers] were, how much they taught us. Especially an illiterate boy like me. To them we owe particularly our sense of the class struggle."

Their sense of class struggle drove workers to defend their rights and to resist their bosses. The editor of El Internacional boasted in 1921 that Tampa cigarworkers were guilty of "the terrible crime of being consciously workers who are always trying to defend their rights and never submit to the false cajolery of the cigar manufacturers." At the same time, a director of the Tampa Cigar Manufacturers' Association charged that cigarworkers were led by "irresponsible agitators who array class against class and teach them that all employers are oppressors of labor and natural enemies of the workers." As late as 1939, a study of Tampa's cigar industry contended that the Latin cigarmaker had "a tendency to take things pertaining to his work or his art, as he thinks of it, very seriously, which frequently leads to his making a major issue out of a very trivial occurrence."

Worker militancy led to frequent interruptions of production. These ranged from brief walkouts by a few dozen workers in a single factory to industry-wide strikes by 10,000 cigarworkers who closed down Tampa factories for months at a time. Strikes by Tampa's cigarworkers rarely focused on the bread-and-butter issues of wages and hours. Instead, cigarworkers engaged in prolonged battles over issues related to control of the workplace. In fact, these struggles can be classified as "control strikes," the term used by historian David Montgomery to describe "the effort by workers to establish collective control over their conditions of work." In strikes between 1887 and 1931, Tampa cigarworkers typically walked off the job in disputes related to the power of foremen, union recognition, and defense of work rules. Explaining the nature of the ongoing power struggle with employers, the editor of the cigarworkers' local union newspaper asserted in the midst of the 1910 strike, "The union is convinced that the only way to make the manufacturers respect it is through a display of its power, consequently it will use power as long as it be necessary, until the total ruin of the manufacturers' capital be the final outcome."

Factory owners saw the conflict in similar terms according to Tobacco Leaf, a trade journal, which reported in 1910: "The battle which has been going on in Tampa for the past fifteen weeks was not, truthfully speaking, a strike, as the word is accepted. . . . It was a struggle . . . on the part of a clique of excitable and irresponsible cigarmakers . . . to install the workman in the place of the employer."

In their struggles with manufacturers, cigarworkers could bring enormous leverage to bear. Their skills and extraordinary sense of solidarity meant that striking workers were not easily replaced. In fact, they usually did not even bother to set up picket lines. Tampa cigarworkers were also part of a larger community that encompassed Key West and Havana where strikers could find financial and moral support.

However, cigar manufacturers could also shift production to branch factories in other cities. This option not only reduced the economic impact of strikes but also aroused concern among Tampa businessmen who feared that factories might permanently leave Tampa, as they had earlier left Key West due to labor troubles. Speaking for the local business community that depended on the cigar industry, the Tampa Tribune declared during an 1899 walkout, "Tampa can afford to lose cigarmakers. Tampa cannot afford to lose cigar factories. . . . Every influence, every sympathy of the people of Tampa should be with the factories." In line with this view, Tampa's business and professional elite consistently intervened in cigar strikes on the side of employers. This outside intervention took a variety of forms, including mediation efforts, but it relied on vigilante violence organized and led by prominent Tampans. The use of illegal coercion by the local establishment often shifted the balance of power in the cigar industry to assure the defeat of workers during strikes.

The pattern of antilabor violence emerged in 1887, as a result of the first prolonged disruption of Tampa's budding cigar industry. With Cuban workers organizing to "struggle against 'bossism' as well as against the monopolies of the wealthy class of the world," a strike over the firing of a popular foreman led Spanish factory owners to complain to the Board of Trade about "interference and attempted intimidation [by] a few Cuban outlaws now in Tampa." Responding to an appeal for assistance, the Board of Trade adopted a resolution formally pledging to cigar manufacturers that the board "will guarantee them full support and protection for their lives and property by every legitimate means."

Leading businessmen immediately made it clear that "legitimate means" included vigilante methods. At a public meeting called by the Board of Trade, prominent Tampans drew up a list of 11 Cuban "suspects" and appointed a Committee of Fifteen, "composed of the best and most responsible businessmen," to run the alleged troublemakers out of town. The vigilante committee was chaired by General Joseph B. Wall, a state senator and vice president of the Board of Trade, who had been disbarred in federal court five years earlier for leading a Tampa mob that had lynched a white transient for attempted rape.

In addition to expelling the so-called "agitators" in 1887, the Committee of Fifteen formally warned cigarworkers against any further disruption of Tampa's main industry. A notice read in English and Spanish in each of the factories announced:

We are here as the representatives of the good people of this community to say that we intend to have order, peace and quiet prevail in our midst, and we give this notice that all disturbers and agitators must leave at once without further notice.

In justification of "our action as a community," the local newspaper editor who served as secretary of the Committee of Fifteen declared, "We are an order-loving people, and do not propose that any band of outlaws and desperadoes shall come into our midst and disturb our peace, order and business prosperity."

Similar economic concerns led Tampa businessmen to form vigilante committees during subsequent strikes. In 1892 the Board of Trade organized a "Committee of Twenty-Five" to police a cigar strike after the Tampa Tribune warned about "the damage the general business interests of the city would sustain" if the walkout continued. Explaining the supposed causes of labor disputes, the Tribune argued that when Cuban and Spanish workers were "subjected to the devilish influence of even one unprincipled socialist, communist or anarchist, they are transformed into little less than madmen." The newspaper noted a resulting local disposition to force "the anarchists to leave the place and the state, and if they do not go when ordered then the danger would come, as some favor swinging their carcasses at a rope's end." The threatened violence did not occur in 1892, but a spokesman for cigar manufacturers boasted that at least one strike leader left Tampa one week following formation of the vigilante committee. Moreover, the strike collapsed soon after the vigilantes, again led by General Joseph B. Wall, took to the streets.

During the 1890s Cuban cigarworkers focused their organizing efforts on the struggle to free their homeland from Spanish rule. Once this was accomplished in 1898, immigrant workers again confronted employers over work-related issues. A brief strike in 1899 produced a complete victory for Tampa workers who won removal of scales that several employers had introduced to weigh the tobacco for each cigar. Strikers also gained a uniform scale of wages for all different sizes of cigars. The 1899 strike was unusual both because cigarworkers won all their demands and because Tampa businessmen failed to intervene. The quick victory showed that employers were willing to accept workers' demands if increased costs could be passed along to the consumers and if they did not involve union recognition.

Nevertheless, the setback encouraged increased cooperation among employers. In the midst of the 1899 strike, the largest factory owners formed the Tampa Cigar Manufacturers' Association for "protection against this labor trouble." Despite continued competition for markets, manufacturers generally cooperated thereafter in the "group handling of labor relations."

Centralization of the industry also enhanced the power of employers. In 1901 three of Tampa's largest factories were purchased by the American Tobacco Company, a trust owned by the Duke family of North Carolina that had already achieved a monopoly in the manufacture of most other tobacco products including cigarettes and snuff. The trust managed to gain control of less than one-sixth of the nation's cigar industry, which was still largely nonmechanized and decentralized with thousands of separate companies. However, the so-called "trust factories" employed about 20 percent of Tampa's cigarworkers, and the American Tobacco Company's widely publicized opposition to unions undoubtedly stiffened the resolve of independent manufacturers to resist collective bargaining.

During the twentieth century, the biggest strikes in Tampa's cigar industry occurred at approximately 10-year intervals in 1901, 1910, 1920, and 1931. Under the leadership of several different unions, each of these upheavals halted the local production of cigars and crippled the city's economy which depended heavily on the wages of cigarworkers.

In 1901 immigrant workers demonstrated their commitment to militant trade unionism when they walked out in support of "La Resistencia," a local union whose declared purpose was "to resist the exploitation of labor by capital." In a typical editorial, the radical union's weekly newspaper, La Federacion, explained, "The organization of labor that is not planted squarely on the class struggle can develop only in one direction — the direction of a buffer for the capitalist class."

The 1901 strike was precipitated by the attempt of La Resistencia to win the union shop for its more than 4,500 members who made up 90 percent of the industry's labor force in Tampa. The largest manufacturers responded that "we will not open our factories until we can control and run our business to suit ourselves." Given its strength, La Resistencia promised a peaceful strike, and its leaders called on "the business men of Tampa, if they cannot help us, to at least occupy neutral ground."

The strike proceeded peacefully, but Tampa businessmen did not remain neutral. Warnings of vigilante violence circulated widely. The Tampa correspondent for a tobacco trade magazine reported at the end of the first week of the strike, "There is a strong probability that if things don't change pretty soon, Judge Lynch will take a hand — not to hang anyone, but a few leaders may find it expedient to change the base of their operation." With local businesses "becoming seriously affected by the strike," the Tampa Tribune soon announced that an end was in sight as a result of a plan that had been "very carefully considered and arranged, and by people who have the welfare of the city at heart."

Meanwhile, an armed Citizens' Committee kidnapped 13 strike leaders who were then loaded on a chartered boat and shipped to the deserted coast of Honduras. The Resistencia men were left with the warning, "Be seen again in Tampa, and it means death."

The anonymous vigilantes issued a statement explaining that their purpose was to remove "anarchists and professional labor agitators" who were trying "to destroy this prosperous city." The deportation committee successfully concealed the identity of its members, but the Tampa Tribune claimed, "The very best business sentiment of the city actuated and executed the step." On the question of possible legal objections, the newspaper concluded, "No well-intentioned citizen is disposed to grumble over the banishment of the Resistencia leaders, because public policy, in some cases, must rise superior to strict legality." Approval of vigilante methods came from newspaper editors around the state including one who observed, "Tampa is largely a law unto itself and has probably hit upon the only way to effectually hold its foreign labor element in check."

However, the forced deportation did not break the strike. La Resistencia members immediately replaced the missing men and pledged to fight on. A local Italian-language paper declared defiantly, "The bourgeoisie of Tampa are not accomplishing anything else but injecting in the minds and souls of the workers a most tenacious and long lasting resistance." Many strikers may have felt this way, but continued resistance also brought more vigilante violence.

The anonymous Citizens' Committee continued to focus its attacks on strike leaders. Two weeks after the first expulsion, vigilantes forced another 17 leaders, including an editor of La Federacion, to leave town. In announcing the forced departure of two more Resistencia men, a manufacturers' journal confided that "the deportations will only cease when the strike is settled, or when every cigarmaker who is addicted to the speechmaking habit has departed."

When the absence of several editors failed to prevent La Federacion from appearing, members of the Citizens' Committee raided its office and dismantled its press which they carted away. The vigilantes also destroyed La Resistencia's soup kitchens which had fed strikers. Finally, the armed Citizens' Committee protected strikebreakers who gradually returned to the factories. Four months into the strike, almost half the cigarmakers were back at their benches, and La Resistencia called an end to the walkout. The radical union never recovered from the defeat, and it soon disappeared.

When immigrant cigarworkers subsequently turned to the Cigar Makers' International Union (CMIU), an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor, they found that even American citizens were unwelcome in Tampa if they were organizing cigarworkers. In 1903, CMIU representatives from outside Florida received threatening notes after arriving in Tampa. James Wood, an organizer who apparently took too much time in leaving town, was shot on his way out of the state and lost an arm as a result. Wood could not identify the attackers, but the CMIU branded the assault "a cowardly and criminal attempt on the part of the trust and other nonunion manufacturers to prevent the organization of the workers in the South."

While Tampa's cigar industry steadily expanded, the working conditions of employees deteriorated. In the absence of effective organization cigarworkers could not enforce wage scales, and pay varied widely from factory to factory. Employers also abused the apprenticeship system to hire cheaper workers. When the Cigar Makers' International Union mounted an organizing drive in 1909, workers poured into the AFL union which soon had over 7,000 members in Tampa. The CMIU's cautious international president, George W. Perkins, tempered his elation with a plea to Tampa workers to avoid "hasty or ill-advised strikes" and to "be guided by fearless and conservative leaders." Perkins also reminded national CMIU officials that in Tampa "the 'Citizens' Committee' were [sic] ever ready to back the employers in any effort to stifle the growth of unionism."

Perkins' worst fears were realized in 1910, when workers waged an unsuccessful six-month strike for the union shop. Although Perkins officially supported the walkout, he later complained that it occurred after Tampa's CMIU leadership had passed "into the hands of the so-called radicals, and the 'fireworks' commenced."

The fireworks included a campaign of vigilante violence against workers. The walkout by 10,000 cigarworkers was peaceful for more than a month, when suddenly a bookkeeper at one of the factories was shot and critically injured by bullets that reportedly came from a crowd of strikers. Two Italians, who were not cigarworkers, were soon arrested for the crime. Within hours the two men were lynched by a well-organized gang of 20 to 30 vigilantes who seized the prisoners while two guards were transferring them from one jail to another. Although the lynchers were never identified, the Tampa Tribune claimed that the summary punishment of "the hired assassins" demonstrated that "the people who have built up this city and who have protected its interests and its welfare in the past are not to be found wanting at this critical juncture." A tobacco trade journal declared bluntly, "The recent 'neck-tie party' . . . suggests that the citizenship of Tampa are at last fully aroused to the fact that the commercial interest of the city is in jeopardy." Support for this view of the lynching as establishment violence came from an Italian vice consul who investigated the double murder. After a visit to Tampa, he concluded that "the lynching itself was not the outcome of a temporary outburst of popular anger, but was rather planned, by some citizens of West Tampa with the tacit consent of a few police officers, and all with the intention of teaching an awful lesson to the strikers of the cigar factories."

There was no doubt about who perpetrated the vigilante violence that followed. After an arsonist reportedly destroyed a cigar factory, "the best citizens of Tampa'' organized a formal Citizens' Committee that was headed by Colonel Hugh C. Macfarlane, a former prosecutor and the developer of West Tampa, an adjacent municipality also dominated by the cigar industry. More than 400 business and professional men publicly affixed their names to a set of resolutions pledging that the Citizens' Committee would protect cigar manufacturers "to the fullest extent possible,'' because the industry "furnishes approximately sixty-five percent of the total income of the city and makes a basis for several other millions of dollars being paid in wages annually."

The Citizens' Committee took the law into its own hands in an attempt to break the strike. When manufacturers officially reopened the cigar factories that had been closed for more than two months, over 200 businessmen armed themselves with Winchesters and began patrolling the streets. Their announced purpose was to prevent interference with cigarmakers wishing to return to work, but vigilante squads committed a number of illegal acts in an effort to force strikers back to their jobs.

Members of the Citizens' Committee raided a union meeting at West Tampa's Labor Temple, ordered strikers to leave the hall, nailed the door shut and left a sign reading, "This Place is Closed For All Time." The Tampa correspondent for the manufacturers' organ Tobacco Leaf reported that the actions of the Citizens' Committee demonstrated "to the disturbing element that the men who own property and have a regard for the interest of the city propose to take care of the destinies of the city, even if it becomes necessary to handle a few undesirables without gloves." One of the "undesirables" targeted by the vigilantes was a CMIU organizer from Chicago who was ordered to leave town by a delegation from the Citizens' Committee that included the publisher of the Tampa Tribune.

The crackdown by vigilantes brought only a few hundred strikebreakers into the factories, but it produced a flood of protests from union leaders. The CMIU's local newspaper, El Internacional, condemned the Citizens' Committee as "the Cossacks of Tampa" who were motivated by "the craving for money that has caused a number of heartless, innoble [sic] citizens to disregard Freedom, Justice, . . . and even the Constitution of their own country." Editorials such as this one led to the arrest of El International's editor on conspiracy charges. When this did not stop publication of the union newspaper, members of the Citizens' Committee smashed its press and beat up a printer.

After six months, local unions finally gave up the fight for recognition. Although the vigilantes' back-to-work movement had failed to attract many strikebreakers, it had encouraged a hard line by cigar manufacturers who refused even to talk with union representatives. In a war of attrition, the union locals ultimately exhausted their funds and called for return to work when they could no longer pay strike benefits.

Ten years later Tampa cigarworkers again struck in an attempt to win the union shop, and they had to deal with yet another anti-union Citizens' Committee. Appointed by the Board of Trade, the 1920 Citizens' Committee was charged with enforcing a board resolution which supported the open shop and called upon "all good citizens" to prevent "intimidation, threats, boycotts, or acts of lawlessness." The leadership of the committee reflected its ties with previous vigilante groups. The committee's chairman, a bank president, had been a member of the 1910 Citizens' Committee, as had the two other spokesmen mentioned in the press — another bank president and a vice president of the city's largest department store. The latter was also a brother of Donald Brenham McKay, the owner/editor of the Tampa Times, who had just completed three terms as mayor of Tampa and who had himself played a leading role in the vigilante committees of 1892, 1901, and 1910.

The presence of federal mediators inhibited businessmen from engaging in overt violence in 1920, but the Citizens' Committee mounted a campaign of intimidation. Toward the end of the 10-month strike, soon after the only reported altercation between strikers and strikebreakers, a "representative committee of fifty leading business men" visited union headquarters and, according to a tobacco journal, "in a pointed talk gave these agitators and radicals to clearly understand that this useless strike had to end." In addition, "representatives of Tampa's best citizenship" warned Sol Sontheimer, a CMIU organizer from Chicago, that "he would be held personally responsible for the future conduct of the strike and of the agitators." The CMIU charged that "the drastic action of the Citizens' Committee . . . in plain English [was] a warning to Sontheimer to get out of the city." He remained, but the factories successfully recruited strikebreakers under the protective arm of the Citizens' Committee.

The next significant display of worker discontent came in 1931. Because of rising unemployment and falling wage rates, cigarworkers rejected the conservative CMIU, and over 5,000 of them poured into the Tobacco Workers Industrial Union, an affiliate of the Trade Union Unity League of the Communist Party. During 1931 Tampa cigarworkers engaged in a variety of radical demonstrations, including a celebration of the anniversary of the Russian revolution, which sparked a crackdown by both public officials and vigilantes. One party organizer was kidnapped and flogged by unknown assailants. When disputes between employees and employers resulted in a brief strike, followed by a lockout, leading Tampans formed a "secret committee of 25 outstanding citizens" who, according to the Tampa Tribune, had "the sole purpose of driving out the communists, whether they are communists freshly arrived or long here."

Backed by a sweeping federal court injunction outlawing the Communist cigarworkers' union, the Citizens' Committee endorsed a reopening of the factories on terms set by manufacturers. These terms included preservation of the open shop, nonrecognition of any union, and permanent removal of the factory readers. The unnamed chairman of the Citizens' Committee boasted that his group operated "with the full cooperation and cognizance of the law enforcing bodies, and its every action has been and will be strictly lawful." However, the mere formation of another Citizens' Committee carried with it the threat of vigilante violence. As a local newspaper emphasized, radical union leaders scattered when "it dawned upon them that the citizens of Tampa were taking a drastic hand. In many quarters there was the recollection of another citizens' committee that served in a strike many years ago." Workers who heeded the warning and returned to their jobs undoubtedly remembered the lessons of previous strikes.

One lesson was that establishment violence against workers went unpunished. No one in Tampa was ever arrested or indicted, let alone penalized, for taking the law into his own hands against striking cigarworkers. Indeed, local law enforcement officials either cooperated openly with the vigilantes or conveniently disappeared when Citizens' Committees took action. However, police immediately moved against workers who engaged in isolated acts of violence, and they often arrested nonviolent strikers for a variety of alleged crimes, such as conspiracy and vagrancy.

During the 1910 strike local union leaders complained, "The city and county government are absolutely at the beck and call of the noble 'Citizens' Committee,' and the governor has refused to intervene." The same could have been said of the federal government which never took action against antilabor vigilantes, despite repeated appeals from cigarworkers and their unions.

Federal intervention ultimately encouraged union recognition for Tampa cigarworkers, but it came too late to be of much help to men and women in a dying industry. The depression of the 1930s decimated Tampa's cigar business. As demand for luxury cigars fell sharply, manufacturers around the country shifted to increased production of cheap cigars that could be made by machine and sold for as little as five cents each. Despite growing unemployment, Tampa's proud cigarmakers resisted change by defending wage scales and traditional work practices that made it difficult for their products to compete with cigars turned out by new methods in other cities. Under these pressures, some Tampa manufacturers went out of business and others relocated their operations, including the "trust factories" owned by the American Tobacco Company, which employed over 10 percent of Tampa's cigarworkers until their operations were moved to New Jersey in 1932. Plant closings and removals eliminated 4,000 jobs in Tampa during the 1930s.

Facing the threat of extinction, most of Tampa's remaining manufacturers agreed to union recognition and collective bargaining fostered by New Deal legislation. With the aid of a federal mediator, employers signed a three-year agreement in 1933 that recognized the CMIU in return for a no-strike pledge from workers. Explaining the new approach, a former head of Tampa's Cigar Manufacturers' Association declared, "We have to consider the workers if we want to survive." Neither collective bargaining nor the economic crisis eliminated strikes by militant workers who continued to defend their rights, but changes in the industry did end the use of vigilante violence to break strikes. After 1933 Tampa businessmen relied on federal mediators and arbitrators to resolve labor disputes in the declining cigar industry.

Vigilante violence thrived for almost 50 years in Tampa, but its precise impact is difficult to measure, especially since it was frequently used in tandem with other repressive measures such as arrests and court injunctions. At the very least, violence against cigarworkers prevented them from winning union recognition until 1933. Even though by 1920 Tampa had more unionized cigarworkers than any other city in the country, these workers could not achieve the official recognition that was common in other cigarmaking centers, such as Boston and New York, where antilabor violence did not occur. Even so, despite the short-term success of vigilante businessmen in breaking strikes, they certainly failed to crush militancy among Tampa's cigarworkers. As workers were returning to the factories in apparent defeat after the 1901 strike, one of the strike-leaders summed up the spirit prevalent among cigarworkers throughout this period: "They have vanquished us but not convinced us."

Tags

Robert P. Ingalls

Robert Ingalls is the managing editor of Tampa Bay History, which devoted its latest issue to the history of Ybor City. (1986)

Robert P. Ingalls teaches history at the University of Florida in Tampa. (1984)

Robert Ingalls is an associate professor of history at the University of South Florida, Tampa. A fuller account of the Tampa flogging case appeared in The Florida Historical Quarterly, July, 1977. (1980)