This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 2, "Water Politics." Find more from that issue here.

Water should be cheap, abundant, and essential, because it is the environmental factor that most controls where people live and how they prosper. The history of human settlement has depended largely on the availability of clean, reliable sources of water. Only in the past century, however, have people become aware of the need to carefully monitor water quality.

The residents of Pittsboro, in the central Piedmont of North Carolina, drink water drawn from the main flow of the Haw River, which drains portions of Guilford, Randolph, Alamance, Orange, and Chatham counties before it joins with the Deep River to form the Cape Fear. The waters of the Haw serve industrial, farming, and residential uses in communities along its course. How the stream can continue to serve these various needs, and remain a clean source of drinking water, has been the crucial question raised by the activist members of the Haw River Assembly.

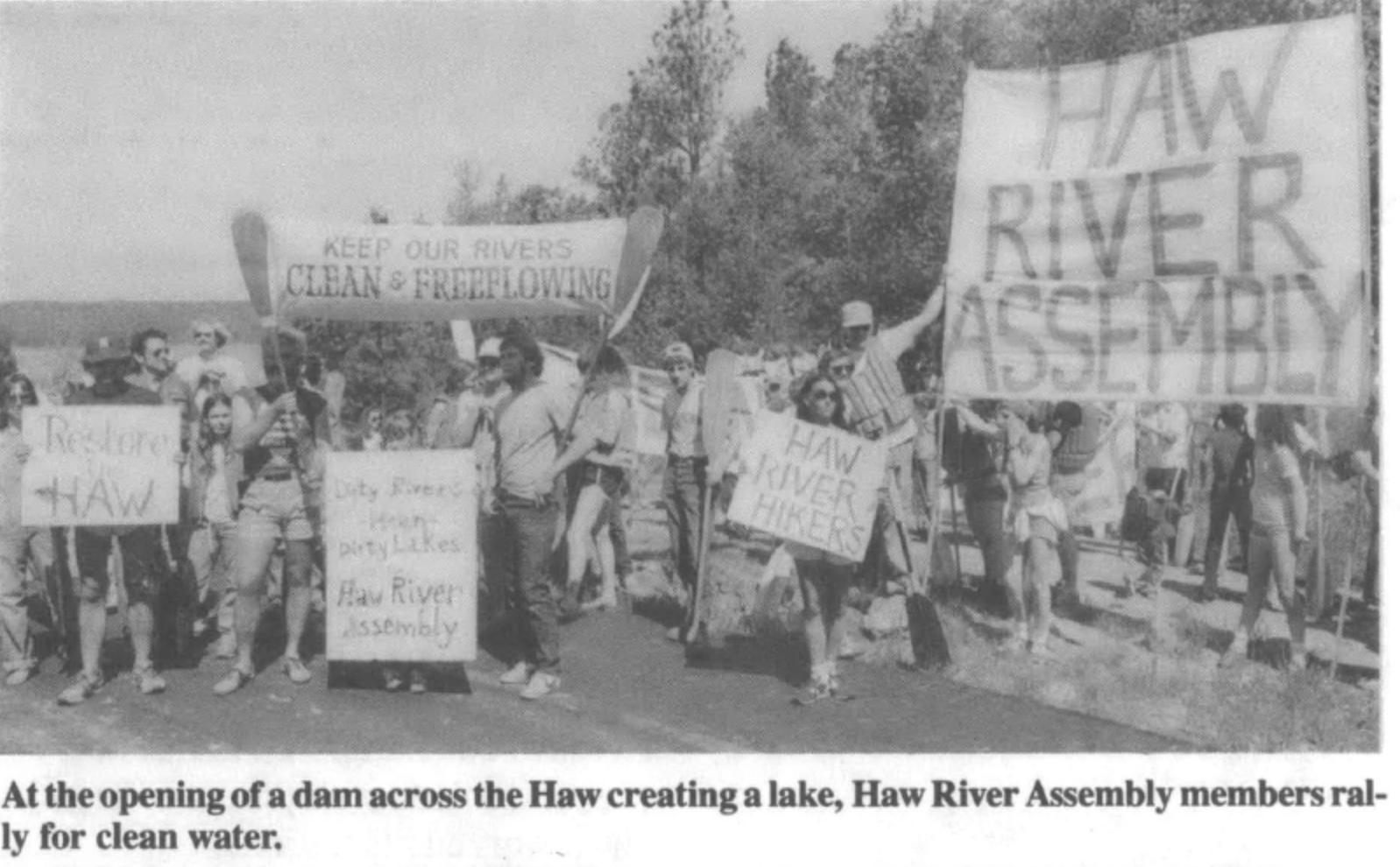

The Haw River Assembly is a citizens’ group formed in 1982 to voice community concerns about the Haw River as a source of drinking water and as a natural recreational area for boating, fishing, and wildlife conservation. The Assembly’s initial membership was a broad constituency that grew in response to a decade-long controversy over the creation of Jordan Lake — a 14,000-acre reservoir created in 1982 by a dam across the lower reaches of the Haw. Besides flooding much of what has been called “the best tobacco land in the Haw River basin,” the lake also posed serious environmental challenges because of upstream pollution. Conservationists feared that the lake would suffer from an excess of dissolved nutrients (such as phosphates) and a consequent oxygen deficiency. After a prolonged legal battle the lake was built anyway, and local conservationists formed the Haw River Assembly to take constructive action to protect the Haw and to educate the public about its scenic, historic, and recreational value. This article is drawn from a lengthy report published in 1985 summarizing the findings of the Assembly’s Water Quality Committee.

History of the Haw

The early history of the Haw River basin was shaped by its rich soil, abundant waters, and the transportation difficulties that hampered trade and prevented the development of large slave-worked plantations.

From the mid-1800s to the turn of the century, cotton mills emerged as a dominant industrial feature of the Haw River basin. The river’s main stream and tributaries provided power for scores of mills, and mills spawned mill towns, where workers often lived in company-owned houses and bought supplies from company stores. The lands remained primarily agricultural, with tobacco and timbering operations emerging to take a prominent place in the economy. By the early 1900s furniture manufacturing, centered in the town of High Point, had also become a major industry in the western part of the basin.

In the early twentieth century several small but significant events took place in the growing town of Burlington, about 27 miles upstream from Pittsboro. In 1919, after a number of water supply wells ran dry, the town installed its first water treatment facility, drawing water through a rock filter system from Stony Creek. When Stony Creek’s flow became insufficient by 1927, the town built a 30-foot dam to create a reservoir from which to supply the growing population. About that time a small company opened Burlington Mills, a pioneer producer of synthetic fabrics and now the giant Burlington Industries. By 1948, fifty manufacturers of hosiery and related products operated within Alamance County alone.

Despite setbacks during the Civil War and later during the Depression in the 1930s, agriculture remained a solid feature of the Haw River basin economy. The agricultural economy took a downturn, however, after World War II. The number of farms decreased between 1945 and 1967, and much of the abandoned farmland reverted to forest.

Today the area is experiencing substantial population growth, due in large part to the booming economies and subsequent population explosions in the neighboring towns of Durham, Raleigh, and Chapel Hill. Experts now expect a growing trend away from agricultural uses of the land and toward increased industrial and residential uses.

Pollutants in the Haw

The Haw river system drains approximately 1,695 square miles of North Carolina Piedmont. The state Division of Environmental Management (DEM) estimates that under low flow conditions the Haw contains 96 percent wastewater; the DEM also reported in 1981 that 39 of 93 permitted dischargers into the river in the regional division that includes Pittsboro were not complying with state water quality regulations.

These noncomplying dischargers included municipal wastewater treatment plants, industries, and residential sewage systems. Combined with chemically laden run-off from road surfaces, farms, and construction sites, this pollution affects not only the river’s ecology but also the quality of the drinking water drawn from it. Moreover, where there is a high demand for drinking water, there is a correspondingly large output of wastewater.

This cycle of use and re-use of stream water for multiple purposes poses a dilemma for public users. Toxic substances, especially when not biodegradable, may become introduced into river water treatment plants, and inevitably into drinking water.

The Pittsboro community — downstream from a heavily industrialized area, surrounded by farmland and managed forests, and encroached upon by rapidly growing bedroom communities — has seen enormous changes take place in the Haw River in recent years, and can expect to cope with even more as the population continues to mushroom and as increasing numbers of industries are encouraged to move to the area.

Focus on Drinking Water

Pittsboro maintains a conventional water treatment plant for processing drinking water for the town and Chatham County’s needs. The plant was built in 1962 and updated to new Environmental Protection Act standards in 1974.

The plant uses alumcoagulation, sedimentation, filtration, and chlorination treatment processes employed by most water plants. Advanced treatment processes capable of removing synthetic organic chemicals have not been implemented. Under current operation, the plant regularly meets the appropriate state and federal standards. The town is fortunate to have competent and dedicated personnel operating its water plant.

Pittsboro’s drinking water system nevertheless faces a number of problems. The current supply of drinking water must soon be increased to serve a fast-growing population. New system design and improved treatment techniques could upgrade the drinking water supply and quality to serve these needs.

In response to community concern about chemical and other pollutants in Haw River water, the Assembly formed a Water Quality Committee to gather information about the river’s chemical pollutants. An ad hoc committee was formed for those interested in investigating the drinking water quality of the Haw. This committee’s project eventually took the form of the Haw River Drinking Water Survey.

Since the Haw River Assembly members felt that the water treatment system was doing an adequate job of processing ordinary sewage wastes the Drinking Water Survey focused on analyzing the presence of synthetic organic chemicals in Pittsboro’s drinking water and Haw River water.

The Drinking Water Survey Committee felt it could help fill the gaps in federal and state clean-up efforts on the Haw River. After consulting with several key figures in local and state water quality programs, the group set up the following objectives for its study:

· to examine Pittsboro drinking water and source water for the presence of synthetic organic chemicals;

· to investigate possible health effects of any chemicals found, using existing research data relating to identified substances;

· to examine available data from previous testing of Haw River water for organic substances; • to determine what substances were being discharged upstream and compile a profile of dischargers and their operations;

· to create public information tools — programs, slide shows, and pamphlets — to educate users and potential users of Haw River and Jordan Lake waters, as well as other state residents, about existing and potential pollution problems;

· to offer solutions, alternatives, and new methods of problem-solving;

· to develop a model for citizen action groups to duplicate or utilize.

In November 1983 the proposed Haw River Drinking Water Survey received unanimous endorsement from the Town of Pittsboro and the Chatham County Board of Commissioners. Seed money to develop the proposal was donated by the New Hope Chapter of the Audubon Society and the Orange Water and Sewer Authority.

In 1983 The Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation awarded a $15,000 grant to the Assembly to begin work on the drinking water survey. The committee contracted with the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering of the University of North Carolina School of Public Health to conduct a chemical screening of the drinking water from the Pittsboro water treatment system for synthetic organic chemicals.

The Results

Two complementary tests for detecting trace organic chemicals in Haw River drinking water and treated Pittsboro water were conducted in February, April, June, and July of 1984. The results indicate the presence of 12 synthetic organic chemicals in the Haw River water and 13 in the Pittsboro drinking water. Five chemicals were common to both waters.

All of the organic chemicals identified in Pittsboro drinking water contained chlorine. Four of the compounds were trihalomethanes, which are currently regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency. Many of these can be formed during the normal drinking water treatment process. These chlorinated organics have also been found in the water from other municipal systems that use the same chlorination method. In this regard, Pittsboro’s drinking water differs little from chlorinated drinking water throughout the nation.

The survey committee undertook a detailed literature search to determine the known health and environmental effects of the compounds identified. Although some of the compounds have been studied extensively, some of the data were contradictory. For other compounds very little or no information could be found.

Adverse health effects of the compounds listed include damage to liver and kidneys, irritation of the skin and mucous membranes, nervous system damage, and respiratory distress. In laboratory animals some of these compounds have demonstrated that they may cause cancer, genetic mutations, or birth defects. Environmental effects include toxicity and bioconcentration in fish, algae, and other aquatic organisms. Although most of the compounds are relatively stable, some break down into other active chemicals. The environmental fete of several of the compounds remains unknown.

A significant fact that became known during this literature search was the lack of consistent data on the toxicology and environmental effects of many of these compounds. This lack of readily available and consistent data underlines the need for more information concerning synthetic chemicals found in the environment, especially about the adverse health effects resulting from low-level, long-term exposure to a given population.

Although the amounts detected were at or below levels considered hazardous to animals, and by inference to humans, we really do not know what levels are hazardous for humans. But because we are subject to so many other environmental and dietary assaults over periods of up to 80 years or more, any additional substances that may cause cancer, genetic mutations, or birth defects must be considered dangerous.

Conclusions and Recommendations

While much remains unknown about the suitability of Haw River water for drinking water use, there is strong evidence suggesting that the presence of synthetic organic chemicals, even at the low concentrations at which they were found, is indeed a problem, and that steps should be taken to address and remedy the problem. The survey committee drew up a list of recommendations, including the following:

· A statewide program should be initiated to educate the public concerning the importance of clean water.

· Research should be undertaken on the toxicology, environmental effects, and breakdown pathways of synthetic chemicals identified in natural waters as well as in drinking water.

· An epidemiological study should be made of the long-term health effects and chemical exposure levels of people who drink Haw River water.

· Individuals and organizations concerned with local rivers should be encouraged to undertake appropriate water quality studies.

· A “Right-to-Know” policy must be instituted. Complete disclosure on a continuous basis by industrial sources must be required to guide permit requirements and monitoring, and to aid in emergency spill response effectiveness.

· The State of North Carolina should further aid industries along the Haw River in cleaning up their waste effluents, keeping them clean, and potentially recycling them into useful products, through an enhanced Pollution Prevention Pays program.

· A faster and more efficient emergency response strategy should be developed to deal with the possible accidents and spills that could result in large quantities of toxic materials suddenly entering the Haw River.

· A monitoring program should be set up to establish a long-term profile of trace organic compounds in Haw River water.

· If further research demonstrates that the presence of synthetic organic chemicals in the drinking water is a consistent problem, then Pittsboro and Chatham County officials should consider possible treatment alternatives to reduce this problem, such as activated charcoal filtration, ozonation, or ultraviolet light.

· At the federal level, the Toxic Substances Control Act should be strengthened, and funding must be provided for enforcement.

Postscript

When the report was published, the Haw River Assembly gave copies to the Pittsboro town manager along with its recommendations. So far, town officials have declined to act, according to Assembly member Tom Glendinning. The group could have exerted some political muscle, but — as Glendinning put it — “where in the watershed do we stop?” noting that waters from the Haw flow all the way to Wilmington on the coast.

Instead, the group has concentrated on influencing state legislation, an activity hampered by its tax-exempt status, which limits lobbying. Currently, members serve as advisers to the Legislative Study Commission on Water Quality. Another Assembly goal is to repeal a state law which forbids North Carolina from setting higher water quality regulations than the federal government, whose standards generally have not been tightened since the beginning of the Reagan administration.

As another follow-up to the drinking water study, the group has begun a survey of cancer rates in a small town along the Haw. One side of town has drawn its water from a state-approved system since the late 1940s; the other side continues to use wells. According to Glendinning, water-system drinkers have experienced a 2,300 percent higher cancer rate than well-water drinkers. The Assembly is working with an epidemiologist to systematize these initial data.

To obtain a copy of the report— which includes a detailed outline of the project process and a sample budget—, send $10 to Haw River Assembly, P.O. Box 187, Bynum, North Carolina 27228. Delivery time is four to six weeks. Copies of the three-page executive summary cost 75 cents. □

Tags

Robert P. Ingalls

Robert Ingalls is the managing editor of Tampa Bay History, which devoted its latest issue to the history of Ybor City. (1986)

Robert P. Ingalls teaches history at the University of Florida in Tampa. (1984)

Robert Ingalls is an associate professor of history at the University of South Florida, Tampa. A fuller account of the Tampa flogging case appeared in The Florida Historical Quarterly, July, 1977. (1980)