Water Politics

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 2, "Water Politics." Find more from that issue here.

What would you do if you woke up one morning to the news that the water coming into your house was contaminated by radioactive polonium?

Like most of us, C. B. Hiscock of Fort Lonesome, Florida, didn't give much thought to the purity of his drinking water - until this February when researchers from Florida State University found radioactive levels in his well 23 times the state standard. Now Hiscock and his family are buying jugs of water at the local Publix grocery store.

According to the Orlando Sentinel, the researchers "are perplexed as to how extensive and how harmful polonium exposure might be - and how to get rid of it." One scientist says the Florida Aquifer, underground source for most of the state's water, is not in danger because polonium - a ''daughter" of unstable uranium atoms found naturally in phosphate ore - loses half its strength every 138 days and "should dissipate" before reaching consumers' taps. Others contend they can't tell how bad the problem is until their study of wells in the phosphaterich, west-central part of Florida is completed near the end of 1986.

Neither the EPA nor the state plans any action until the survey is finished, even though everyone knows the contamination has been worsened by years of phosphate companies' pumping the waste water from their mines into deep sink holes or "recharge wells" that replenish the ground water supply. Regulators are not anxious to throw another hurdle before the powerful phosphate industry which employs 12,500 Floridians and provides 80 percent of the nation's phosphate needs_. After all, the industry already suffers from a declining fertilizer market, increasing foreign competition, and costly environmental regulations.

So while the scientists conduct their study and the regulators wait for the results, Hiscock and his neighbors have abandoned their wells and hope the bottled water they're buying is safe. What would you do if you were in his shoes?

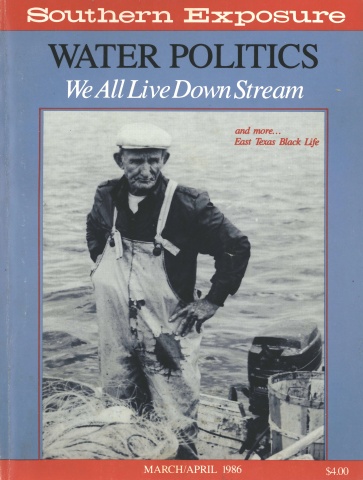

Or what would you do if you were a commercial fisher and one day learned that a ruptured 20-year-old pipe dumped tons of slime into a fertile estuary killing all the organisms on which shellfish feed? Like the disaster that hit C. B. Hiscock in Florida, this one also happened in February 1986. It too involved the phosphate industry's contamination of water, but it endangered a community's livelihood rather than its drinking water.

"This is only the latest in a long list of spills and ruptures and slime pond leaks that have been killing the Pamlico River," say Etles Henries, a fisher who runs the commercial seafood plant begun by his father in Aurora, North Carolina. "Texasgulf acts like their phosphate mine is the only thing that matters around here. They don't want to recognize that the fishing industry has been here for hundreds of years and it still gives work to thousands of people. I don't mind them doing their job, but they shouldn't be allowed to cost me mine."

Regulators in North Carolina are even more lax than those in Florida when it comes to stopping water contamination by phosphate miners. The only phosphate company operating in the Tur Heel state, Texasgulf (a subsidiary of the French-owned Elf Acquitaine) employs 1,300 workers in economically depressed Beaufort County. Although it has been cited by the Army Corps of Engineers and EPA for many regulatory violations, the state has allowed the company to continue mining under a water discharge permit that expired in 1984. "There are too many jobs at risk to close that place down," one regulatory official admits privately.

The politics of polluted water faced by C. B. Hiscock and Etles Henries may seem remote to you. For most of us, water is one of those simple commodities we take for granted. Only when we're deprived of its ready availability do we realize how essential it is to our daily life.

Fortunately, the South as a whole has ample supplies of fresh water, as Robert Healy points out in his new book, Competition for Land in the American South: only 1 percent of the annual renewable water supply in the Tennessee Valley is consumed and less than 10 percent is consumed in the entire Mississippi River basin. But aggregate figures ignore the intensity of the problem for those people whose water supplies are being drained dry or permanently contaminated.

The figures also obscure the common thread running through case after case of water misuse: land-rich corporations earning millions of dollars off the earth's natural or developed resources give no more regard for the water beneath or beside their land than they are forced to. From the forest products firms around Savannah, to the phosphate industry that owns 659,000 acres in Florida, to the energy companies of the Southwest and Appalachia, these corporations take water for granted, like the rest of us, until their own supply is threatened. But unlike us, the scale of their operations means their short-sightedness has immense consequences for their neighbors nearby and far away. As Robin Epstein points out in her article here, the pollution of the Albemarle Sound caused by the average farmer's drainage ditches pales in comparison to what would result from the ambitious plans of First Colony Farms to drain tens of thousands of acres of coastal wetlands, mine the peat off the top, and plant corn on what remains.

Epstein's report is part of a larger study initiated by the Institute for Southern Studies examining landownership in all 100 of North Carolina's counties. In case after case, we found that giant landowners not only control the land-base of a county, but through that control they dominate the job market, politics, tax policy, housing conditions, economic development strategies, and environmental protection measures of the surrounding area. Texasgulf owns 62,000 acres in Beaufort and Pamlico counties. Not far away, Weyerhaeuser (the timber/paper conglomerate) owns one-fifth of Martin County, employs 2,100 people, and is the major consumer - and polluter - of water in the vicinity.

Although all five of these counties are on the coast, they fit the pattern identified in the Appalachian Land Ownership Study (see Southern Exposure, January/February 1982): the counties with the highest proportion of their land owned by absentee corporations are also among those with the highest rates of poverty, substandard housing, and unemployment. And, as you'll see from the profiles of the two mountain communities in this section, they are also the counties with the most grotesque forms of water abuse. In Campbell County, Kentucky-where Melissa Smiddy's well water was threatened by the strip mines circling her home-ten corporations owned nearly half the county's land in 1980. The Appalachian study noted that Campbell County's local development policy jumped to the tune of the corporate interests rather than serving the needs of residents.

Even in the more prosperous urban counties of the industrialized Piedmont, the Institute's study discovered, land-rich corporations and developers still exercise an inordinate influence over the fate of an area's water quality. Consider another example from February 1986, this one from Durham, North Carolina, where Southern Exposure is based. Developers that month won major zoning changes which will allow them to build a massive industrial-residential complex on 5,200 acres between three rivers that feed the region's municipal water systems. They adamantly - and successfully - opposed area residents' demand for an independent environmental impact statement to determine the project's long-term affect on the fragile water ways.

The Durham County Commissioners sacrificed strict land-use regulation in favor of two longstanding principles: (1) people should be able to do what they want on their own land; and (2) any development that improves the county's tax base is beneficial. These two out-dated myths, more than any others, undercut the enactment of systematic zoning and environmental regulations across the South. Wheelers-and-dealers of our land and water resources like it that way, and you '11 find them among the most politically active interest groups in nearly every election, from the smallest county to the biggest city.

Because of the political climate created and maintained by land-rich profit takers in the country as well as in the city, citizens who see their water endangered must fight on a case-by-case basis. They are put on the defensive, called troublemakers, and made to feel isolated and hopeless. But, as you'll see in the following pages, with the right combination of persistence and popular support, everyday citizens are succeeding in protecting the water they need for their life and livelihood.

Indeed, people who wonder whether their water supplies are pure needn't wait to act until pollution becomes obvious. The activists in North Carolina's Haw River Assembly decided to test their local drinking water, prompted partly by their observation that well water drinkers apparently experienced less cancer than those who consumed city-processed chlorinated water. The Assembly's strategy now is to influence state officials and to urge them to tighten water policy standards.

The spirit and the strategies of the "troublemakers" profiled here are inspiring and instructive regardless of where you live. Ultimately, each of them demonstrated that his or her private complaint was a matter of grave public concern: these grassroots activists impressed the politicians with enough people, the bureaucrats with enough paper, and the media with enough drama to transform themselves from isolated victims into well-connected protectors of the American dream. Their victories are not secure, however, because their opponents remain convinced of their own righteousness and they have the money to keep trying new ways to exploit public resources for private gain.

Vigilance against the next scheme of the peat miners or coal processors or urban developers is crucial. We can no longer take water for granted, because if we are not organized to protect our natural resources, someone else will come along and abuse them. It's only a matter of time. We must spend the energy now to learn the value and vulnerability of our water (as well as our land and air) or we're destined to pay a far greater price later to correct its ruin.

The Florida phosphate industry has a slogan they want us to believe: Phosphate feeds you. Nature teaches another lesson: Without water, there is no life. □