The Bridge That Brung You Over

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

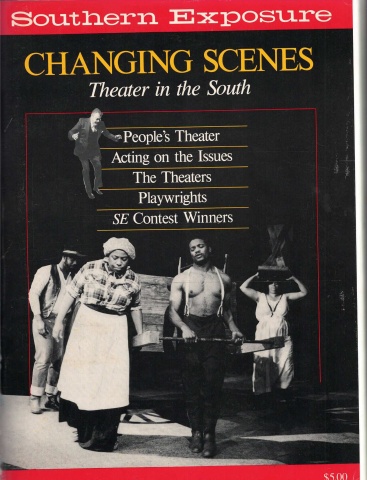

Every Now and Then I Get the Feelin displayed Jomandi's own dancers in a tribute to generations of black dance and dancers.

Atlanta has about three dozen theaters. Two are black, and the rest aren't called white. "White theater" sounds like an insult. It has racist connotations. It feels exclusive, like a club where Williams, Shepard, Shakespeare, and Neil Simon go to drink, where the only blacks are in the kitchen or waiting tables. White theater, egad, who would use such a term? No, they're simply theaters. Just because the majority of the audience is white doesn't mean that blacks can't come if they want to. Hell, their money's good. Of course Shakespeare isn't racist, even though directors insist that most of his roles must be played by white people. There's always Othello and Caliban. Maybe one of the three witches. White theater? Preposterous! Pass the pâté, would you?

Equally weird is the notion of "black theater." It evokes the AfroAmerican '60s, drums, young bloods in loincloth, Nigerian hoedown choreography, a macramé display in the lobby. Or else it's yet another funkless blockbuster, like Ain't Misbehavin' or Dream Girls. Sure it's Broadway, but at least it's black.

Yet black people need to recognize themselves, their lives, up on the stage. And besides, the white people have all those other theaters. Now we're talking about a black-run theater, using black actors, with black plays, for a black audience. Black theater — it sounds independent, righteous, thematically limited, and rather exclusive. It doesn't mean that the white people can't come. Their money's good too.

Jomandi Productions, one of Atlanta's two black theaters, was founded in 1978 by Tom Jones and Marsha Jackson. Jones and Jackson, both educated in New England, gave up graduate school to return South and start their theater.

At first, Jomandi had no permanent home. The company used to play at a community center on the South side, but the location was obscure, divorced from the nightlife, and considered dangerous by black and white alike. Last year, Jomandi moved uptown to the Academy Theater on Peachtree Street in the midst of what passes for Atlanta's theater district. Despite the predominantly white setting, the move has proved advantageous. Jomandi has higher visibility, and Atlanta's other black theater, Just Us, performs right across the street.

Jomandi produces mostly new works — plays by Baltimore playwright Alonzo Lamont, companydeveloped shows, and adaptations such as last season's Cane, based on the novel by Jean Toomer. In Jomandi's early days it used to produce four or five new plays a year. It cut back to two this season, trying to focus resources. "It's hard to do new plays," Jones acknowledges, what with a six- to tenweek development and rehearsal process, compared to a shorter period for established plays. But as Jomandi's reputation gets around, more new scripts are being sent in.

Jomandi has most recently toured with a dance/music/theater collage called Voices in the Rain. It's a collection of work by established artists from Langston Hughes to Al Jarreau, as well as some original pieces by Jones and Jackson. The company developed the piece, and the cast of four was headed by the founders. Jomandi's winter '86 tour of the South was partially funded by the Southern Arts Federation. Three weeks alone were spent in New Orleans, playing to virtually every middle and high school there. Last year, the same show went on the road to Sweden, Denmark, and Germany as part of the Other America Festival, an annual alternative theater tour of Europe.

Meanwhile, guest director Andrea Frye mounted Do Lord Remember Me back in Atlanta, the second show of Jomandi's '85-86 season. It's another company-developed work, based on interviews with former slaves conducted in the '30s under the Works Progress Administration. The February production coincided with Black History Month, although Jackson doesn't characterize the show as a history lesson. "It serves no one if we simply quote facts," she says. She prefers to place black history in the context of progress, using an expression she heard as a child: "Don't forget the bridge that brung you over." She also feels that Jomandi is a bridge, one to the future, from "what is" to "what could be."

But the future, and change in general, are problematic, as was aptly illustrated last season in Jomandi's production of Alonzo Lamont's new play, 21st Century Outs & Back. The protagonist, Daphne, is the daughter of a middle-class family. Her return from college entangles her in family obligations and racial bonds. She wishes, if she could only be free, be her own woman. She has just as much right to be a yuppie as anyone else. No, she doesn't want to be white; but does she have to turn her back on her own mother, her own race, to get free?

Now that's a risky subject — a black woman, sympathetically portrayed, trying to escape a threatening whirlpool of what used to be called black heritage. Jomandi took a small beating at the box office. The company also fielded some complaints from the black audience. But — and Jones and Jackson feel this was their highest praise — some people remarked that the play had made them think, that they just hadn't seen things that way before, and they were grateful.

That's the challenge that Jomandi pursues. The idea is to engage the audience, or failing that, at least get them to consider what Jomandi is saying. Of course, that might mean opening avenues of discussion that people really don't want to pursue. It might mean openly criticizing some aspect of the black community or lifestyle, as in 21st Century Outs & Back. But Jomandi recognizes the importance of self-criticism, despite the pain, because that critical eye frees the black community from the yoke of being judged from a white point of view.

Some people think of black theater as falling into two categories: plays (usually upbeat musicals) which cheerlead the black experience, and dramas (usually depressing) which chronicle the unjust victimization of the black people. Much of this, but not all of it, is true. Playwrights like Ed Bullins and Lorraine Hansberry have laid the ground work for something else, a theater that reaches beyond narcosis and despair.

Black theater could offer the black community more than simple recognition that it does exist. "Theater could draw from the life and blood of the black community," Jones argues. In examining the specifics and nuances of human relationships, theater explores the hows and whys of existence. Most of all, theater can be a humanizing medium. That is, when a play' s investigation of the human condition is more than skin deep, the findings are universal — good for blacks, good for whites, good for all of us together.

That's the kind of theater that Jomandi wants to be.

Not that tt isn't. On its last tour of Voices in the Rain, audience participation once stretched the running time of the show from the usual 45 minutes to an hour and a half. Jones's "street blood" characterization rallied a good bit of audience feedback. And Jackson's fundamentalist preacher's monologue had the audience shouting "amens" and humming in chorus, just like at a Sunday morning service.

Jomandi's greatest problem, a problem, incidentally, shared by all of Atlanta's theaters, is its lack of a strong, visionary director. Its productions don't have the focus provided by one mind/one director. Instead, Jomandi operates on a collaborative basis, capitalizing on the various talents in the company, adapting to one another's contributions. In the process, the company struggles to develop a working vocabulary for its art, trying to capitalize on its diversity. Jomandi's shows don't have a smooth homogeneity, but they do bristle with the enthusiasm of creation.

It's hard to write about the future, and harder to build a bridge to it. Artistically, Jomandi is healthy and growing. It has had to put more ambitious plans on hold, however, until it can gather more personnel and funds. Funding is erratic. Atlanta and Fulton County governments have largely black administrations, which doesn't hurt when arts grants are doled out. But the economy of Atlanta is still in white hands, and corporate sponsors are wooed only by proof that a theater has a large audience, preferably one that drinks Coca-Cola. (Coke maintains its corporate headquarters in Atlanta.)

So if Jomandi thrives, it will be because it produces quality theater. That is, of course, if quality theater has an audience. If it does, it's probably made up of quality people. And quality people, no doubt, are curious, able to withstand and generate change, and unwilling to let racism stand between them and a good time.

Tags

Tom Boeker

Tom Boeker is an Atlanta theater critic who writes for Open City magazine, Creative Loafing, and Atlanta magazine. (1986)