This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Academy Theatre is Georgia's oldest professional resident theater, located in Atlanta on Peachtree Street.

Academy celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. The company is in the process of building a new theater scheduled to be completed in December.

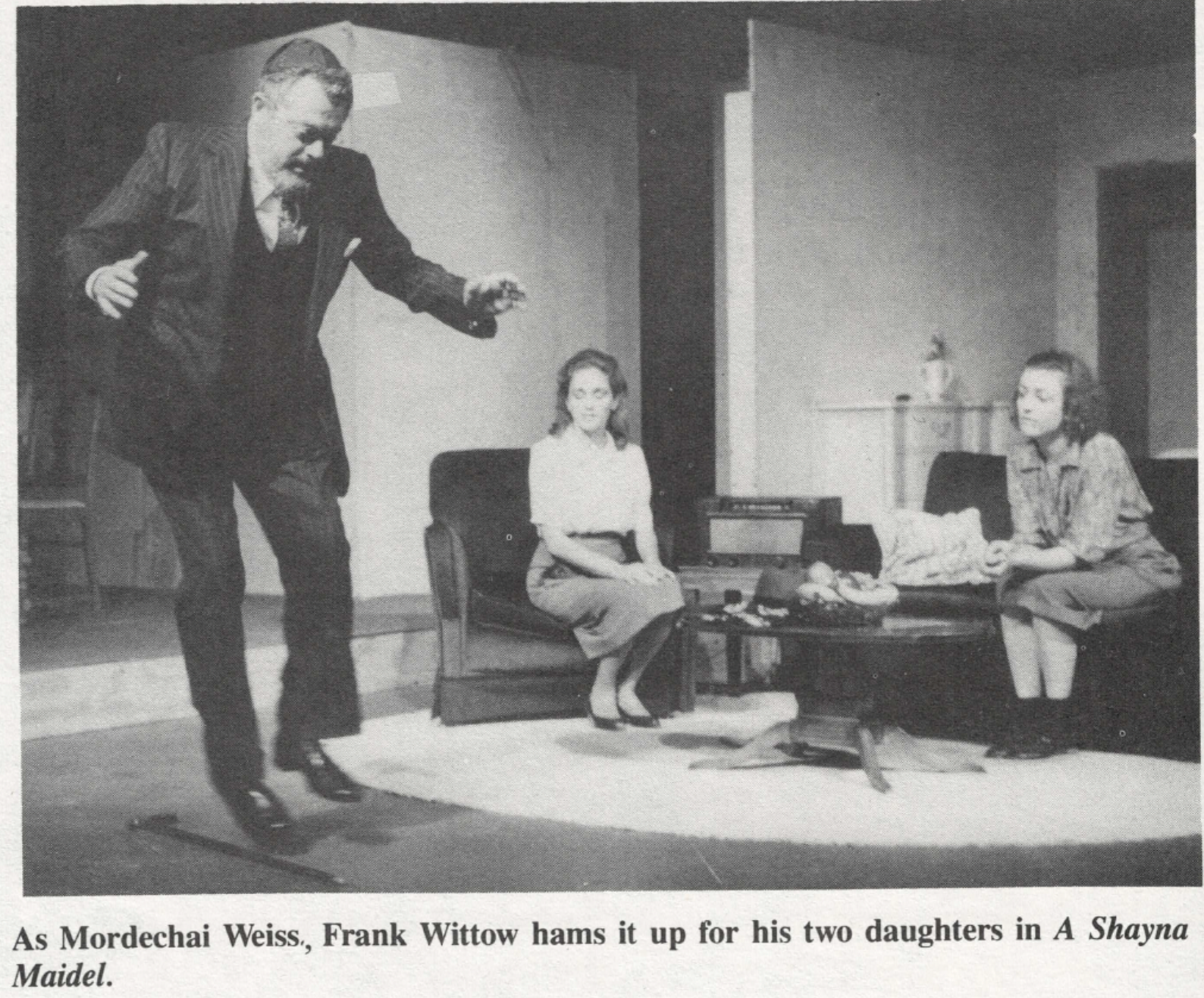

The powerful voice behind this longlived theater is Frank Wittow. Wittow was born in Ashtabula, Ohio in 1930. His parents were first-generation Jewish-Americans, whose parents had emigrated from Eastern Europe. Wittow grew up in Lorain, Ohio, a steel-mill town of about 50,000 people, many of whom were Slavic immigrants of Roman Catholic or Eastem Orthodox faith. This interview was conducted by guest editor Rebecca Ranson and took place in Wittow's office at Academy Theatre in May 1986.

As a freshly minted college graduate, Frank Wittow was drafted to direct a theater company in his hometown:

In the fall of l953 after I had just finished my Master's degree at Columbia, I went home to Lorain, Ohio. It was during the Korean War and I was waiting to be drafted. I got a call from some people at Lorain Community Theater who said they were just about to fold. They had $15 left in their bank account and they had heard that I'd done some theater work in college. As a last resort, they wanted to talk to me about their situation. They were looking for some kind of inspiration. They thought I was a lot more experienced in theater than I was.

I didn't disillusion them. I said I would take over and try to do something as long as they let me do anything I wanted to do. They said OK. So I went to the library and got a book on directing theater, because I had never really directed. I had done a little theater in college but my formal education was in psychology. I didn't have much respect for theater as it was practiced or theater people. I thought they were all rather supercilious, not serious enough for my taste, but there was something in me that needed that kind of exhibition.

I looked for a space and found a Slovenian Social Hall. The rent was $75 a month, so I committed the theater to that. Suddenly — from being ready to quit — we had a theater building to remodel. It was very exciting. People came down to repaint the building and refurbish it, and it became a focal point for that community at that time.

In an amazingly short time we had about a hundred members. I started classes for children. I became artistic director of the theater without really having had directing experience, let alone teaching experience. It was a great act of chutzpah. I was doing everything from designing the sets to teaching and directing, doing the business and advertising. And everybody thought I knew what I was doing.

For me, without question, it was the most exciting and challenging thing I had ever done. I had found something at last that was really meaningful — far more meaningful than what I was pursuing in terms of school psychology. I thought theater could be a way of doing everything I had hoped to accomplish in psychology but with much more freedom.

From the time I was a sophomore in high school, what I was gonna be was very, very important to me. It was more important to me than to the other kids. I was very concerned about who I was, and what I was gonna do in life. I thought if I could help the world by curing all the emotionally disturbed children — well, boy, what a contribution to mankind! It was that simplistic. That's how the choice became school psychology. It was very idealistic. Then in the community theater, I saw the possibility that those needs on my part could be legitimized by giving something to the community.

It struck me that theater was an area where you could define what you were doing and the objective. It was my first discovery of what it could mean to dedicate one's life to the arts.

Up to that time, I felt my that any interest I had in theater was purely self-serving, purely to indulge myself in exhibitionistic tendencies and needs, a very selfish kind of thing. I had been to Northwestern [as an undergrad] which was sort of a springboard to stardom. It's the same now I think. People go to college in order to make it in "show biz." Some kids at Northwestern had ideas of going off and starting little theaters. But the main idea was making it in New York. That's what I didn't like, what I didn't feel at one with. I had to deal with my own need to perform and show off, but I never could see that as a serious way of life because it seemed so totally self-serving.

As a graduate student in New York, Wittow had encountered professionally ambitious actors:

I met the "show biz" people, saw Broadway and thought it was a lot of fun but silly, not serious enough for old Frankie. Even in New York I remember wondering why all these talented people weren't out in their hometowns with all their gifts instead of flooding New York with all this competition and horseshit. That was 35 years ago.

I thought they could really be giving something to people who had nothing and instead they were all competing. There was no regional theater at that time except maybe Margo Jones in Dallas. People that I went to school with at Northwestern were in New York and I saw them and it didn't seem to make any difference whether they were not successful or they were successful. They were all worse off as people. I don't think it's changed a lot.

The U.S. Army's draft eventually cut short Wittow's involvement with the community theater in the Slovenian hall:

I was drafted in June 1954. I went to basic training at Fort Knox in Louisville and was transferred to Atlanta as a personnel psychologist. I had never been to Atlanta before and I fell in love with it immediately. The second day here I took a stroll and walked up Ponce de Leon and up Monroe and ended up on Peachtree. I walked past what was then the art museum and some nice ladies saw me, this soldier boy, and invited me to attend a chamber concert. They were lovely typical Southern ladies, and I thought they were wonderful. I walked a little further until I came to 13th and Peachtree. There was a movie house, Peachtree Art Theater, and next door to it was a record shop. That record shop is now our first stage. There was a guy there and I started asking him what was going on in the theater and expounding on my ideas of theater and talked about starting my own theater. You can imagine how I felt when we bought this building.

I also called the library that day and found out that there were three amateur theater groups at the time. One of them was the Atlanta Civic Theater, one was The Theater Guild, one was the Playmaker's, a new group that was just starting.

I called the Playmaker's and they were having auditions that Monday. So I auditioned for John Loves Mary, and got cast in the lead. My whole Army career I was doing theater work constantly. In a sense that was my first government grant. I was subsidized. I did get called to the colonel's office many times for reading plays on duty and having my head shaved because I was playing a part.

The February before I was to be discharged, I had met enough people and done enough work that I decided to stay in Atlanta and start a theater. My first theater that was my own opened two days after I was discharged from the Army, June 20, 1956. It was financed with my Army discharge money.

From a modest beginning, Academy Theatre has expanded into an organization with three acting companies that produce about four plays a year on its main stage and another four on its first stage. For 16 years Academy operated out of a neighborhood church, which was sold. In 1977, the company moved on to an enormous theater at Center Stage:

I was frightened to make that leap from a 200-seat theater to a 700-seat theater, but there wasn't much else available and we had to keep operating if we were going to survive. There was some indication that it might really work and it did seem to work. We went from no subscribers to 2,000 subscribers just like that. We went from 50 students a quarter to over 200 a quarter. We had one of the best ensembles we had had in a long time.

Suddenly we were visible. We had been in Atlanta 20 years but no one knew about Academy. People who stopped coming to the church [theater] because we were doing experimental work started coming back and saying that we had a "real" theater. It's what I call shit flies. We were a larger turd

then and attracting a lot of various shit flies. We then began to draw larger audiences than we ever had before. We haven't come close to that kind of attendance for an individual show since then. The second year the landlady doubled the rent. That was a big nosedive for us that we have barely recovered from now. It was just disastrous. That was the closest we came to being a big operation.

To consolidate resources, Academy relocated to smaller quarters, first to Erlanger in 1970) and then to its present location in 1982.

Now during the year I meet with everyone in the theater to see how they're doing and to talk about next year. That is the heart of this theater. In order for me to be happy with what I'm doing, I try to maintain that kind of personal relationship and knowledge of the people I'm working with so I can facilitate their growth as much as possible. The theater has to be a size that I'm capable of keeping in intimate touch with.

For Wittow and the Academy Theatre, the economic struggles always continue:

They never let up. It's a question of how bad it gets. The point is that if you're a non-profit arts organization you're always striving to pay people something, at least a wage they can live on, which we never can do. We're at the lower end of the pay scale. Sometimes we go through a whole season and manage to pay everybody on time. Very often, such as the last two years, paying salaries on time is a major problem. We get behind by weeks and people are caused great hardship.

It's not poor planning or being extravagant. Sometimes there is not the fundraising that is planned or some programs don't come through. It's always a struggle. We constantly work on ways to keep it from being debilitating and sapping energy from the artistic area.

As a versatile theater veteran, Wittow has performed in virtually every capacity of the profession: acting, directing, writing, producing, business managing:

I think acting is the most painful and tension-producing [aspect of theater] for me. I would be very proud as a writer if I could produce a script I really liked. For me, all of the experiences from teaching and directing to writing mean something and all require a different combination of abilities.

I find it fascinating to work with people in different kinds of relationships. I look for company members who are versatile and who are interested in developing in different ways. I think it's a good learning process. I like to think of the theater as a place where we're all continuing to learn. If there were one thing that I loved before all the others then I would just do that but I like all of it.

Once a ham, Wittow in his middle years finds that his youthful exhibitionist streak has faded:

One of the main changes I notice [ since I first worked on stage] is that whatever I'm doing or the theater is doing, the base of satisfaction has changed. It's changed from, "Look at me, look at what I can do," to, "It's a privilege for me to be able to give something that's important and to focus more on the worth of what we have to offer people of the community." I think the beginning of a theater is primarily an ego thing.

Unless you find something much deeper than your own ego gratification, you will give it up and go be a star in New York or Hollywood or somewhere. If you stick with it then there has got to be something profound. Academy has survived because I found a meaning that was much more significant than anything else I could think of doing with my life.

Tags

Rebecca Ranson

Rebecca Ranson is a playwright who is a native of North Carolina. The author of over 30 plays produced in many cities across the country, Ranson bases most of her work on voices of the oppressed. (1986)