This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

In the 1910s moving from the farming community of Lillington, North Carolina to the state university in Chapel Hill meant much more than traveling the 50 odd miles of dirt roads and railways. Only the most privileged or the most determined could make their way from a life of labor and commerce to a life of letters and ideas. And even the determined ones needed a little luck.

Paul Green, a determined 23-yearold farm boy from Harnett County, scraped together his first year's tuition from his meager salary as the principal of a small country school and from his earnings as an ambidextrous pitcher for Lillington's semi-pro baseball team. Still, he wouldn't have been able to complete his first year if the University of North Carolina had not hired him to teach a freshman English class.

This freshman teacher-of-freshmen had never seen a play performed, but he entered a campus play-writing competition that year and won the cash prize of $5 — about the price of a new suit. Green's first play — like many of his later works — hit close to home in a Chapel Hill only two generations removed from the humiliating defeat in the Civil War. Surrender to the Enemy told the true story of the controversial love affair between Brigadier-General Smith B. Atkins of the Union occupation forces billeted at the university in 1865, and Ellie Swain, the daughter of the university's president. The play premiered in an open-air theater on the campus on May 3, 1917, as part of the annual Community Spring Festival.

Green later recalled his first firstnight jitters: "I sat on the bare hillside and sweat streamed under my clothes." The author reviewed his first theater piece with his feet, as he "stumbled and fled . . . frightened by the life and blood of the thing."

Green's attack of nerves was probably unwarranted. The audience, gathered on scattered rugs and pillows in a sloping campus glade, had witnessed the first faltering steps of a most remarkable career. The next six decades would lead this embarrassed novice to Broadway and Hollywood and back to North Carolina while he matured as the South's first modern playwright. Before his death in 1981 at the age of 87, Paul Green would be recognized alongside Tennessee Williams and Lillian Hellman as one of the South's most important playwrights. And unlike Hellman or another North Carolina writer of his generation, Thomas Wolfe, Green spent most of his life developing his craft in his native state.

Since his childhood, Paul Eliot Green was fascinated by words, books, and storytelling. As the oldest son on a small Southern cotton farm in the years before World War I, he could steal away to write in the woods only on "wide and soundless Sunday afternoon(s) ." His formal education began in one-room log buildings with classes conducted a few months out of the year. Eventually he graduated from the local Buies Creek Academy (which later grew into Campbell University), and at the age of 19 became principal of the school in Kipling, North Carolina. From there he had worked his way to UNC and his first playwriting award.

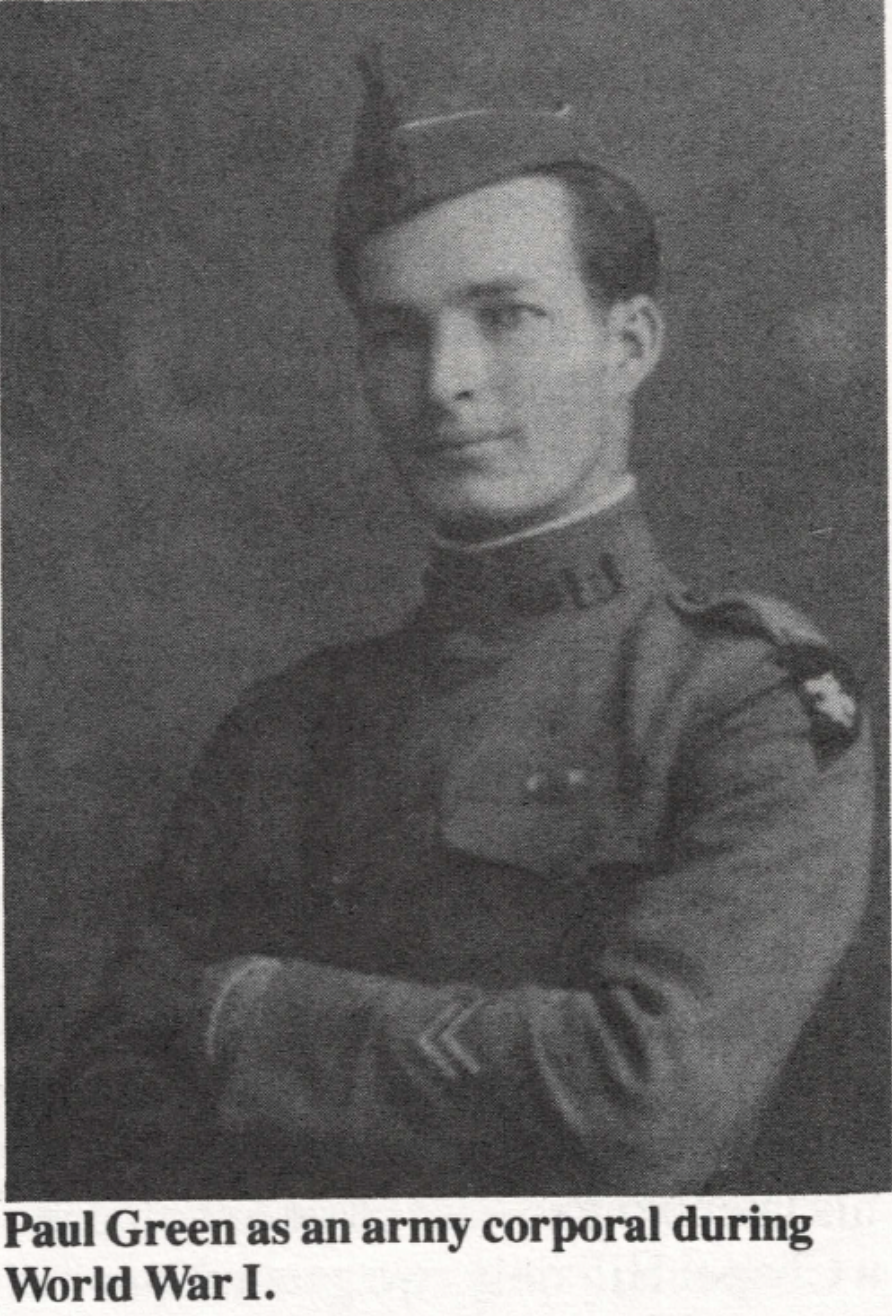

Two months after his first opening night in 1917, Green enlisted in the army, on the strength of Woodrow Wilson's rhetoric and on the weakness of Green's own prospects for raising the next year's tuition. While "in the muddy and death-rotted trenches of Flanders, sitting in the oozy dripping earth," Green began to consider writing novels and perhaps even plays as vehicles to express his personal vision.

Following two years of military service in Belgium and France he returned to the university in 1919. While overseas he had not tried his hand at play writing again. But in Chapel Hill he was lucky enough to meet a great new teacher of play writing, Dr. Frederick H. Koch.

In 1918, while Green slogged through the Flanders mud, UNC hired the Harvard-educated Koch to teach play writing in the English Department. "Proff' Koch, as he came to be known to a generation and a half of students and theater enthusiasts throughout the Southeast, had studied under the pioneer theater educator and literary critic George Pierce Baker. Between 1905 and 1935, Baker's "47 Workshop" at Radcliffe, Harvard, and later Yale was the North American outpost for a rebellion in acting and play writing which had already swept Russia, Scandinavia, and Ireland. Baker and the Europeans before him wanted to free stagecraft from the 19th-century conventions of wooden, declamatory melodrama and museum-piece reproductions of the declamatory melodrama and museum-piece reproductions of the classics. An activist generation led by Ibsen, Strindberg, Chekhov, and Stanislavsky struggled to introduce realism and naturalism into the modem theater where the characters related to each other on stage as living, breathing humans, not as two-dimensional, posturing caricatures. Baker was instrumental in spreading the revolution among his students who — besides Koch — included such illustrious and innovative artists as playwright Philip Barry, critic and play editor Theresa Helburn, director Elia Kazan, educator Kenneth MacGowan, play wright Eugene O'Neill, and novelist Thomas Wolfe.

After a stint teaching English at the University of North Dakota, Koch had arrived in Chapel Hill as an apostle of naturalism and a proponent of the theories of Baker and the Irish poetplaywright William Butler Yeats. Yeats and his celebrated Dublin-based Abbey Theater sought material for drama in the folk life of the common ordinary people of a region or country. Koch encouraged his students to forego melodramatic fantasies about exotic "captains and kings" and to write about the things they knew firsthand. He urged them to turn to their own experience, including the history and vernacular of their home communities. Koch called it folkdrama. As much an impresario as an educator, Koch founded the Carolina Playmakers during his first year on the UNC campus. One of the oldest university theater companies in the South, the Playmakers then performed not only at the university but took their shows on the road, carrying props, playbills, and Koch's theater gospel into communities in Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

Once Green returned to Chapel Hill, he began turning out plays for Koch's student company in his spare time. Under Koch's influence, Green mined the material he knew best, the speech and characters of rural North Carolina.

Green finished his undergraduate work in philosophy in 1921 and the following year married a fellow campus poet-playwright, the Playmakers' field organizer, Elizabeth Lay. Lay had made history herself on campus as the first woman to act in a theatrical performance, raising eyebrows and overturning tradition at the predominantly male institution.

Green moved on to graduate study at UNC and Cornell in philosophy. He accepted a post as an instructor and later assistant professor in the philosophy department at UNC, a position he held until 1939.

Black Folk Drama

From the time of his return to the university until the mid-1930s, Green's plays, short stories, and novels primarily chronicled the lives of tenant farmers and rural tradesmen — black. white, and Indian — in his imaginary "Little Bethel" community. Green had grown up working and playing side by side with some of the South's most economically hard-pressed people. Although Green's father had always owned enough land to hire tenant labor, their farm was of modest size. In the parlance of the day, they "lived at home" — meaning that, in addition the cotton cash crop, the family raised all its own food.

By literally reading while he plowed, Paul Green had been able to escape a life of farming, but the lessons and the rhythm of that life never left him. In the grinding physical routine of farm labor; the rugged, uncaring hostilities of weather, pestilence, and disease; the changeless cycles of hope, frustration, generosity, and violence that move through an isolated rural community, Green found ample material to produce an impressive body of literature. In this early work — written during time squeezed from his research and teaching responsibilities — Green examined not only timeless themes in human experience but the particular realities of life in the rural South during the first four decades of the 20th century.

Green described himself in those days as "having a chip on my shoulder" and thought of himself as avid disciple of cynics H.L. Mencken and Sinclair Lewis, while claiming Jefferson and Wilson as his political models. From his early experiences in Hamett County, Green felt he had "developed some fellow feeling for people who have to bear the brunt of things." But he moved beyond mere social realism or muckraking. In those early years, he achieved what no white North American author had before him. He wrote about black men and women, not as the grinning stereotypes or scraping caricatures, but as fully developed human beings. His works followed the actions of complex individuals involved in dynamic dramatic struggles, in settings that were true to Southern black experience. When actor Paul Robeson turned down Green's request to play the title role in his 1927 Pulitzer Prize-winning Broadway play, In Abraham's Bosom, Robeson paid Green perhaps the highest compliment that a black actor could pay a white play wright. Having read the play before meeting Green, Robeson told him, "You know, I rather thought you were a Negro."

It was no surprise that when Cheryl Crawford, a co-founder of the avant-garde Broadway company the Group Theater, approached Richard Wright in 1940 to adapt his controversial bestselling novel Native Son for the stage, Wright asked Green to collaborate with him. The son of Mississippi tenant farmers, Wright greatly respected Green's work, having performed in the Chicago production of Green's scathing attack on prison chain gangs, Hymn to the Rising Sun.

The Search for People's Theater

Several of Green's one-act and full-length plays were produced on Broadway. But Green found the New York theater industry unsatisfying. He quickly grew tired of Broadway and wrote that "my theater for the present is the published play." He later blamed himself for being ignorant of the realities of the industry, of "expecting too much." During that period he discovered that "the New York stage is an industry, not an art as I had dreamed." It was "dog eat dog and look to your suspenders."

The New York theater, Green felt, was too far removed from the lives and experience of ordinary people. He sometimes spoke of the need to "whittle" Broadway down. In all fairness, Green could never entirely shake the country person's intuitive distrust of noisy, crowded cities and sophisticated ways of life.

Green's limited formal training in theater also contributed in part to an anti-elitist element in his world view. His mentor Koch was less interested in developing Tar Heel Shakespeares and Molieres than in awakening his students and the local community to the drama in their own lives. As a professor of philosophy and later of dramatic arts, Green continued Koch's tradition when he told his own students, "You have seen a great deal. You will see more. Tell us about it."

Green didn't characterize his direct, no-nonsense approach as a theory of aesthetics, but he fervently believed that all the arts "fill human needs and feed human hungerings." He argued that "the arts are just as necessary to the full man or the nation as bread and meat and sweat and work. And so they are a part or should be a part of the human regimen." In this sense, he said, "every man is an artist just as every man is a worker."

At the same time, Green distrusted art that became "a special thing with its own vocabulary from its own ritual and mystique, too far away from the checks and balances of life." The traditional centers of art, like New York, claimed to have a monopoly on theatrical talent, goods, and services. Green wanted to find a way to decentralize, democratize, and redistribute. He described his vision as People's Theater.

Soured on Broadway, Green went looking for new ideas, methods, and approaches, first off Broadway and then abroad. In 1928, on a Guggenheim Fellowship, Paul and Elizabeth Green went with their two children to Berlin for a year and a half to study contemporary European theater. Green's spirits reached perhaps their lowest artistic ebb that year, and he discussed with his wife abandoning the theater entirely. She reminded him of the exciting impression a recent piece had made on him. In Three Penny Opera Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill had made great use of music in advancing the themes of the play. She suggested that her husband consider making more use of music, as well.

While Green was in Berlin, he met another visiting folk-dramatist, Alexis Granowsky, the artistic director of the Moscow-based State Jewish Theater, the foremost Yiddish language troupe in the world. Granowsky had spent the previous 10 years experimenting with "musical theater," a combination of music, dance, pantomime, costumes, and lighting to give the words of a play deeper meaning. Green was swept away by the company's performances, and he discussed with Granowsky on several occasions his theories and their application to folk material.

When Green returned to the U.S. the running battles with the Broadway establishment continued. When he visited New York, the city was still intrigued by the rustic philosopherplaywright from down South who could quote both the Bible and Aristotle at cocktail parties. In 1931 Green's House of Connelly launched the career of the Group Theater, Broadway's most innovative performance and training ensemble in the years before World War II. And later his Hymn to the Rising Sun played in Chicago and New York. But Green felt restless on the East Coast, and he again turned elsewhere for inspiration and ideas.

Green had been "moviestruck" from the time he first saw Charlie Chaplin in 1919 in a French cantonment for American soldiers. He claimed to have seen Chaplin's Gold Rush at least 14 times. Faced with supporting four children and a wife on a Depression-era assistant professor's salary, Green quickly realized that he could make more money in three weeks in Hollywood than he could during an entire academic year in Chapel Hill. In 1932, Green arranged the first of several short leaves of absence from faculty responsibilities. Like so many other creative writers of his generation — including Fitzgerald and Faulkner — Green boarded the train to California.

He was excited about the creative possibilities of films, particularly their power to alter time and space and to combine images and sounds for a total effect on the viewer, much as the Russian State Jewish Theater had affected its Berlin audiences. Film technology now allowed an artist to reach a wider audience in the most remote corners of the world than any previous medium.

But Hollywood was no more able to fulfill Green's artistic expectations than Broadway. While he produced over 40 scripts during his screenwriting career for stars such as Will Rogers (State Fair), Bette Davis (Cabin in the Cotton), George Arliss (Voltaire) and Gary Cooper (Broken Soil), Green was continually frustrated by studio-controlled formula of cheap endings, unrealistic characters, teamwritten films, and a prudish moral code.

Despite his frustration, Green earned good money working for the major studios, which enabled him to achieve an important degree of financial independence. In 1942 he moved his family to Santa Monica, California. Two years later, at the age of 50, he left the university faculty permanently. Not until 1963 did he write his last film script, the film version of John Howard Griffin's book, Black Like Me, the true account of an ingenious attempt at participant observation of race relations in the South. But neither films nor California could keep a permanent hold on Green. By the end of the 1940s he had returned to Chapel Hill, devoting himself almost exclusively to his work with his new dramatic form, symphonic drama.

Symphonic Drama

Throughout the 1930s Green had sought to adapt the experiments of Brecht and Granowsky to his own dramas. He coined the term "symphonic drama" to describe his attempts to integrate music, dance, dialogue, poetry, plot, scenery, costumes, lighting, and special effects into an organic, artistic whole. He drew the term from the root meaning of symphony in Greek, "a sounding together." In pursuing these efforts, Green thought of himself as a composer or conductor who makes use of the different voices of the orchestra, "driving forward a composition. . . . The entire body of the piece must be kept moving along, by means of the individual instrumentations that [come] forward to personal fulfillment, turn, retire, and give place to others and they in succession likewise. Character and story motifs must be developed, thematic statements made and exploited, and an upboiling and stewing of symphonic creativity kept going toward a dynamic finale."

Green experimented with his ideas in four early musical dramas produced on Broadway and college campuses between 1932 and 1936. In 1934 Roll, Sweet Chariot featured a cast of over a hundred black actors and singers. A highly symbolic meditation on contemporary black life, it was based on previously written sketches and plays about Carrboro, a mill town near Chapel Hill. The fourth play in this initial series of symphonic dramas was a highly acclaimed collaboration with a refugee from Nazi Germany, Kurt Weill, who had scored Brecht's Three Penny Opera. Premiered in 1936 by the Group Theater, Johnny Johnson was a hard-hitting satire on war and modern organizational society, drawn in part from Green's experiences during World War I. This play gave Broadway its first experience with Weill's haunting melodies. In this last musical piece for Broadway, Green introduced to modern theater audiences the now-classic scenes of the lefthanded soldier training in a righthanded army and the simple enlisted man who confronts and makes a fool out of the government psychiatrist.

Green felt symphonic drama reached maturity in his most widely produced play, The Lost Colony. He had long considered doing a play on England's first attempt to establish a permanent colony in North America between 1584 and 1587 along the present-day North Carolina coast. When a newspaper editor from Elizabeth City, North Carolina approached Green about writing a play commemorating the 350th anniversary of the birth of the colony's first baby, Virginia Dare, Green was extremely wary. He feared the business community 's desire for a sideshow play for tourists was diametrically opposed to his own concept of People's Theater.

Green managed to win a guarantee of complete artistic control and a role in the larger management of the project. He also convinced the Federal Theater Project to sponsor the production, which opened in July 1937 in a specially built open-air theater on the presumed site of the colony outside Manteo, North Carolina. Green and others arranged for FDR to attend a special production on August 18, 1937, Virginia Dare's 350th birthday.

The play was an immediate hit. Originally intended to run only for the summer of 1937, The Lost Colony has continued in performance every summer since then, except during the war years of 1942-45. It is estimated that over a million people have seen the play.

Green's 20 other open-air history plays follow a formula first worked out in The Lost Colony, with a few variations. Each is based on a significant local historical event, often performed at or near the site of the actual event. The plot focuses on the activities of one or two historic or invented figures who, in resolving an important personal crisis, shape the later history of the region, state, or nation. Green personally researched each story and documented or created a cast of supporting characters, most of whom were drawn from the ranks of common

working people who made vital, often little-recognized contributions to history. All the productions included pageantry and lots of music.

These plays and dozens by imitators have proved immensely popular over the years with local audiences and seasonal tourists. Six of his plays are still in annual production in five states, selling over 300,000 tickets in the 1985 season.

Green's dramatic experiments fortuitously coincided with the development of the South's modem tourist industry. His symphonic dramas and their imitations became the basis for a new profitable product in that industry. Today the Chapel Hill-based Institute of Outdoor Drama provides services to over 55 ongoing productions in 23 states. The realities of weather and dependence on tourism dictate that the majority of these productions are in the South. During the 1985 season, outdoor dramas sold over 1.4 million tickets and grossed over $8.8 million.

In the course of his work on symphonic dramas, Green's own strongly held political views came into sharper focus. Since the early 1920s, Green's work had stressed the importance of the individual and the choices he or she makes in moments of personal or community crisis. Before The Lost Colony, Green generally found it less important whether the person succeeded or failed, than that the person struggled. In fact, from the "Little Bethel" stories through his first experiments with symphonic drama, the works often ended with the central characters falling victim to social, economic, or psychological forces outside their control. In his later dramas, however, Green unabashedly chose to write about heroes. These plays enshrine the individual and his or her actions within a setting of basic paradigms from the American dream — hard work, honesty, commitment to goals, belief in progress, and the ultimate triumph of good. The central characters in works from this period rarely fall victim to events but rather shape history.

Green's later, more upbeat world view appealed not only to outdoor drama audiences but to foundations and government agencies outside the Broadway and Hollywood establishments. In the years after World War II, Green received three Freedom Foundation awards and a Rockefeller Foundation grant to lecture on theater around the world and to act as a consultant to set up regional drama centers in the U.S. He also served on the Executive Commission of the U.S. National Committee for UNESCO and was installed as a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.

Green ended up disturbed by the financial and popular success of his People's Theater movement. He was convinced that it had fallen prey to the "materialistic philosophy afflicting the whole Western world." Production standards in some of the dramas had dropped. The movement had gone "commercial" and become increasingly a social organization controlled by educators, and college and civic leaders who preferred to "get things on a business basis" and play it safe. Many annual productions had become routine and lacked dedication and vision. Worst of all, from Green's point of view, the movement had become "producing theater instead of playwright's theater." None of the outdoor plays he read in later years had "any real lift and reach in the language."

Green's Legacy

Remaining a full-time writer until his death at 87 in 1981, Green just refused to quit working. His death cut short plans to drive to Texas to discuss a new production. Perhaps partly because of his refusal to stop writing, Green seemed to outlive the historical significance of some of his greatest accomplishments. His groundbreaking work in folk drama and black theater was followed by successful collaboration with the preeminent innovators of pre-World War II Broadway, then success in popular films, and finally his bold attempt to merge serious theater with historical pageants. Spurred on by his intensely idealistic determination to avoid having his art be controlled by commercial constraints, Green seemed to end up very close where he had begun, struggling to improve an artistically immature commercially successful drama form.

Perhaps with the exception of Johnny Johnson and Native Son. Green's work is largely ignored today by literature students and major theatrical producers, and it will probably continue to grow in importance more for social historians than for aspiring playwrights.

Sometimes it seems that the major theme in Green's life was leaving things behind: He left the farm, he left folk drama, he eventually left Broadway, he left academia, he left movies, and right up to his death, he was challenging his colleagues in outdoor drama to improve their work or perhaps leave the field. But Green did not so much abandon earlier commitments as he built upon them to enlarge his capacity to express his dreams.

Throughout his restless career, two things remained constant for Paul Green — his love for the South, and his commitment to creating theater that served the needs of ordinary people in telling their stories and inspiring them to keep building up their personal and collective dreams. And that remains perhaps his greatest legacy to the artists, activists, and audiences who pick up where he left off.

Tags

Larry Vellani

Larry Vellani is co-director of the North Carolina Prison and Jail Project, Inc. and the producer of "Lone Vigil," an annual arts event which commemorates Paul Green's contributions to the struggle for social justice and benefits the work of North Carolinians Against the Death Penalty, which Paul Green co-founded in 1967. (1986)