This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Since scholars began gathering oral histories in the 1930s, these taperecorded autobiographies of everyday folks have traditionally served as primary documents for social historians. Recently, however, these life histories are finding their way out of the archives and into the public’s reach. Not only through popularizers like Studs Terkel but also through public radio and television programs, film, theater, and various public history events, the voices of ordinary men and women now speak to a broad audience.

The distinctive voices some of the South’s Piedmont workers -over 300 men and women from industrial communities in North and South Carolina -have been captured on tape by the Southern Oral History Program (SOHP) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and are on deposit in the Southern Historical Collection. Since industrial development occurred in this region within living memory, the SOHP was able to explore the important transition from “farm to factory.” Program director Jacquelyn Hall explains, “We thus had the opportunity to pose questions about that transition to people whose roots lay in a preindustrial past and whose destinies were shaped by the emergence of industrial capitalism in the region.”

From the outset the SOHP sought to reach beyond academia for its audience as well as its sources. Program staff are especially eager to return the fruits of their labor to the people who shared their personal histories and to solicit their responses to the program’s interpretation. To that end, the SOHP has commissioned a play based on the interviews, and plans a series of history workshops designed to bring audiences into a dialogue about the human consequences of industrial development.

The impetus for this project grew directly out of Echoes in America, an ambitious collaboration which had as its centerpiece the touring of an oral history play called Echoes From The Valley. This play painted a picture of life in the textile towns along England’s Aire River during the first half of this century, as “told “ by some 40 former textile workers whose taperecorded interviews were woven together for the drama by British playwright Garry Lyons.

Lyons found the process intriguing: “From a writer’s point of view it’s obviously always difficult to imagine the way other people live or lived and . . . to characterize them in their own language. [By using oral history] there’s an authenticity that would be difficult to write or recreate imaginatively.”

In collaborating, Lyons said, “Oral historians and playwrights are rediscovering lost experiences and then presenting them before the public.”

Julia Swoyer, whose Iron-Clad Agreement Company specializes in the production of plays focusing on workers’ lives, saw Echoes From The Valley in Yorkshire, England in 1983. She then came up with the idea of “tracing the textile industry (from England) to New England and then down South.” Swoyer thought that “people in those regions — both textile workers and former textile workers —might feel a kinship with the English people and their stories. The stories would be in a different dialect, but there would be a humanity that would be similar and interesting.” She felt that post-performance discussions and history workshops would give audiences of diverse backgrounds an opportunity to share and compare their own histories.

Echoes in America toured Rhode Island, Connecticut, North Carolina, and South Carolina in the spring of 1984. After one performance in Concord, North Carolina, a resident who had worked in a Concord textile plant for 49-and-a-half years before retiring in 1978 shared her thoughts with those assembled. She remembered narrowly escaping injury once when her father pulled her from the grasp of a machine belt which caught her skirt. But, like the workers from the Yorkshire mills, she recalled those work days fondly: “I loved it. . . a lot of people say the noise is too much, but it never bothered me at all — it’s just like music to me.” She remembered becoming eligible for a paycheck on her 14th birthday and recalled that the first day’s check for $1.60 “seemed like a fortune.”

The audience in a Bynum, North Carolina, Methodist Church was impressed and “tickled “ with the stories they saw reenacted in their church-turned-theater. Many commented on how their working lives in the Bynum mill had been like the British experiences.

The reactions were not uniformly positive, however. “New Englanders had a closer link with Yorkshire workers, as many were children and grandchildren of immigrants from the British Isles,” said Lyons. “They felt they were hearing stories of back home. This wasn’t so true in the South where families had settled generations before. Although stories of work were similar, there was not such a close identification with the working people of Yorkshire.

“In the South, I detected something I hadn’t elsewhere. There was a defensiveness on the part of some people who thought we were showing the textile industry in a bad and unfair light and that the content of the play focused on poor working conditions. I think that, if anything, that defensiveness is a reflection of the differences between the industry in Britain and the South.”

Still, the SOHP was inspired by the similarities in its interview collection with those in Echoes. The program decided that the time was ripe for a play using the voices of Piedmont workers, and, with funding from the North Carolina Humanities Committee, commissioned Garry Lyons to create the play script.

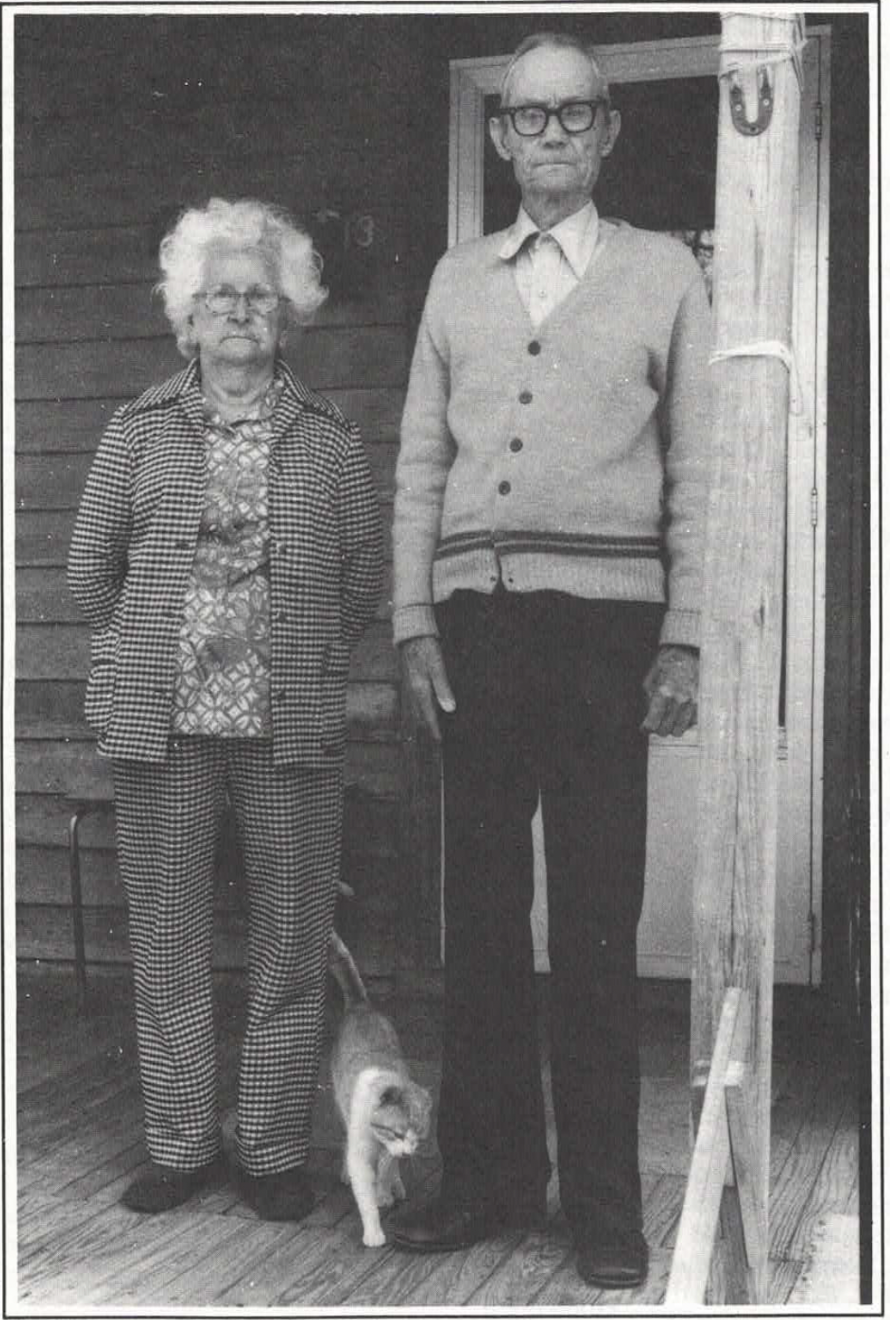

In August 1984, Lyons came to Chapel Hill to read the oral histories and explore the region about which he would be writing. He attended a Durham tobacco auction, and consulted with area string band musicians for tunes many workers would have listened to during the 1930s and ’40s. He visited a small, essentially unchanged mill village just outside Burlington, now a major textile city. There he talked with retired mill hands.

Armed with a wealth of materials, Lyons returned to his home in Leeds, England, and set to work stringing together interviews with other source materials to form a play. The result, entitled Plant Me A Garden: An Oral History Play of the Carolinas, weaves oral history vignettes into a cohesive and compelling drama.

Four main characters provide the core of the play: Annie, a black tobacco stemmer from Durham; Mack, a white Greenville, South Carolina, textile worker; Ethel, a white weaver from Burlington; and Chick, a politically active black tobacco worker from Winston-Salem. These four characters assume the identities of people introduced in one another’s reminiscences, thus suggesting a larger context. This kind of character development allowed Lyons to explore the range of issues reflected in the Piedmont interviews.

“I had to cope with a greater diversity of experience,” said Lyons, “particularly the black experience and the tobacco industry. Experiences were not quite so homogeneous (as in Britain) and this affected the way I structured the play. Instead of using Echoes’ model structure — that of a typical day — I tried to go for a historical sweep across several decades.”

Industrialization and change were greatly condensed for Southerners from the tum of the century to World War II, which Lyons said, made “life change more rapidly in the South than it did in Yorkshire.”

Plant Me a Garden was more complex than Lyons’ original play for other reasons as well: “As I wrote, I tried to select material that was interesting from an outsider’s point of view. Racial differences, or indeed, racial similarities, provided some of the most interesting materials. Gender is a microcosm of a larger truth. Rich versus poor is a global issue. These materials add ‘color’ to the play and help the region’s distinctiveness get through.”

Yet, according to Lyons, there were similarities between the Carolina and Yorkshire interviews: “The lot of the working man and woman is very similar worldwide, after all, and this is what makes the (oral history) material play to diverse audiences — allowing for differences, of course, in race and gender.”

The SOHP is now seeking ways to produce Plant Me a Garden. After an opening run, the play will tour the Carolinas’ textile and tobacco communities.

Tags

Amy Glass

Amy Glass is the Administrative Assistant for the Southern Oral History Program ar UNC Chapel Hill. (1986)