This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

"I know this isn't directly related to what you're doing, but I thought you might be interested." I wonder how many projects, literary or otherwise, start with that introduction.

Some stories seem to choose you.

Preacher With a Horse to Ride is based on events in the coalfields of eastern Kentucky following the Depression. In early 1931, Harlan County miners attempted to get union recognition from the United Mine Workers. (See Southern Exposure, Vol. IV, Nos. 1-2, 1976 "The Battle of Evarts.") Although the miners organized a number of successful mass protests, marches, and walkouts,

UMW had privately joined the coal operators and local officials in thwarting the organizing drive.

Tensions flared, and on May 5, three mine guards and one miner were killed in a gun battle. The entire leadership of the organizing drive was arrested on charges stemming from the shootings, effectively putting an end to the union movement in "Bloody Harlan."

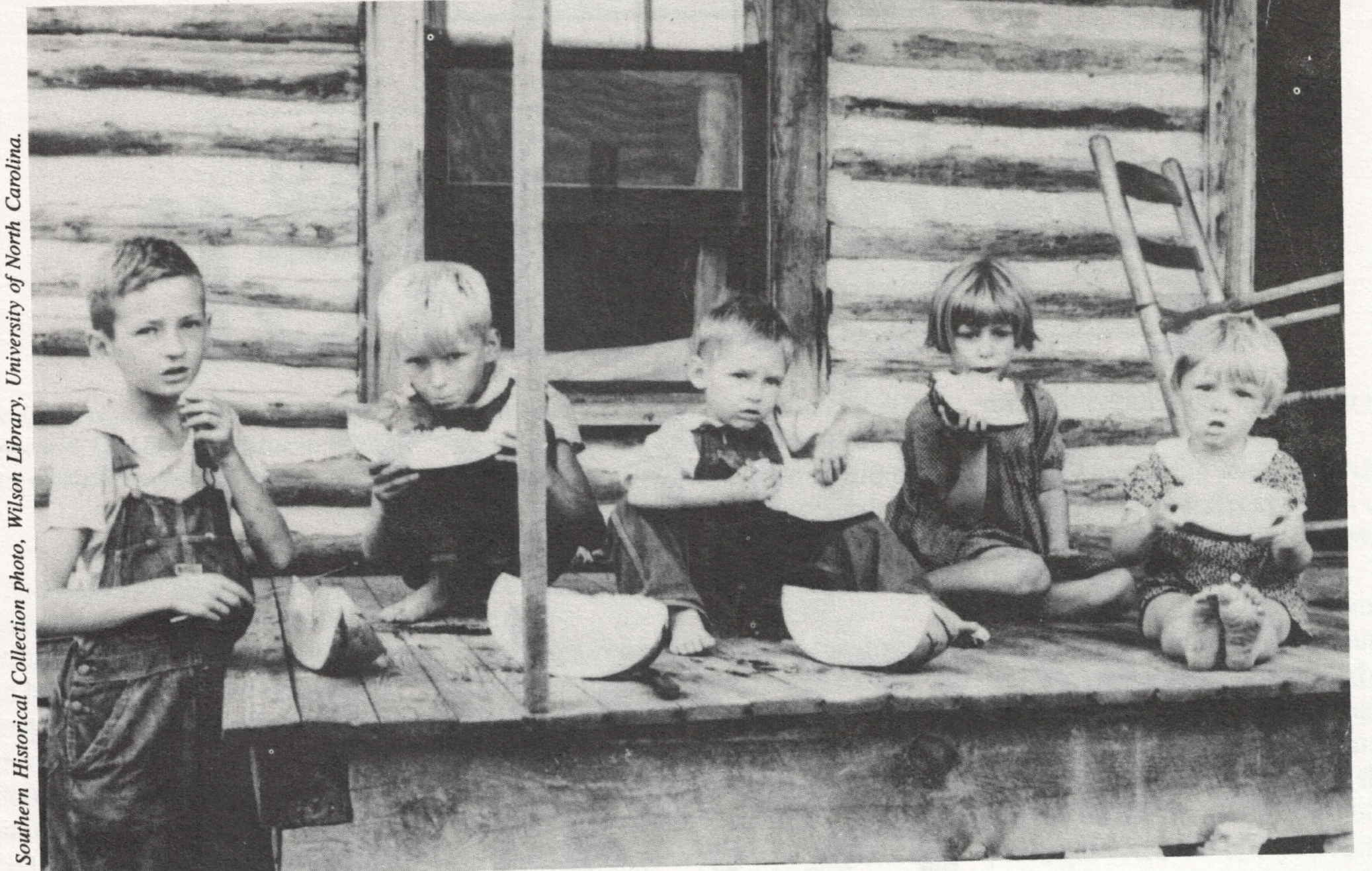

The communist-led National Miners Union stepped into the void, but by October their efforts, too, were floundering. In November, the NMW brought novelist Theodore Dreiser and seven other writers and activists to hold unofficial hearings in Harlan to revitalize the organizing drive and to bring attention to the widespread abuses of miners' rights and the injustices and poverty rampant throughout the coalfields. The committee hoped that the hearings would bring pressure to bear on the local power structure as well as to raise money for striking or blacklisted miners.

After a University of Kentucky archivist sparked my interest in the story, I read extensively about the place and time, about the Communist Party, the unions, the music, the church. I read most all of Dreiser's published work and talked to people who remembered "the troubles." There was so much that wanted telling, and I took liberties in presuming I could put words in the mouth of Dreiser or Molly Jackson or any of the others.

I was warned once that a writer must not confuse the facts with the truth. Until I started trying to write this play about people who lived a chunk of history in the region where I live and work, the remark passed by me lightly. It does not pass lightly anymore.

Excerpt not included here. Copyright by Jo Carson.

Tags

Jo Carson

Poet, playwright, and author Jo Carson is Southern Exposure’s fiction editor. (1995)