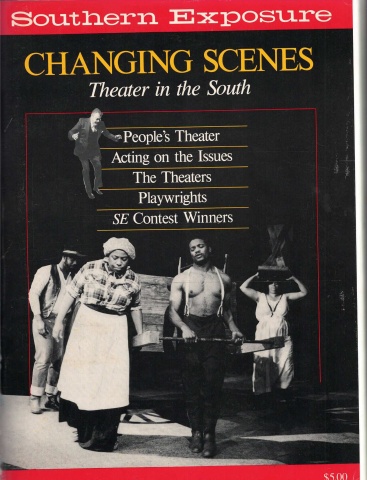

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

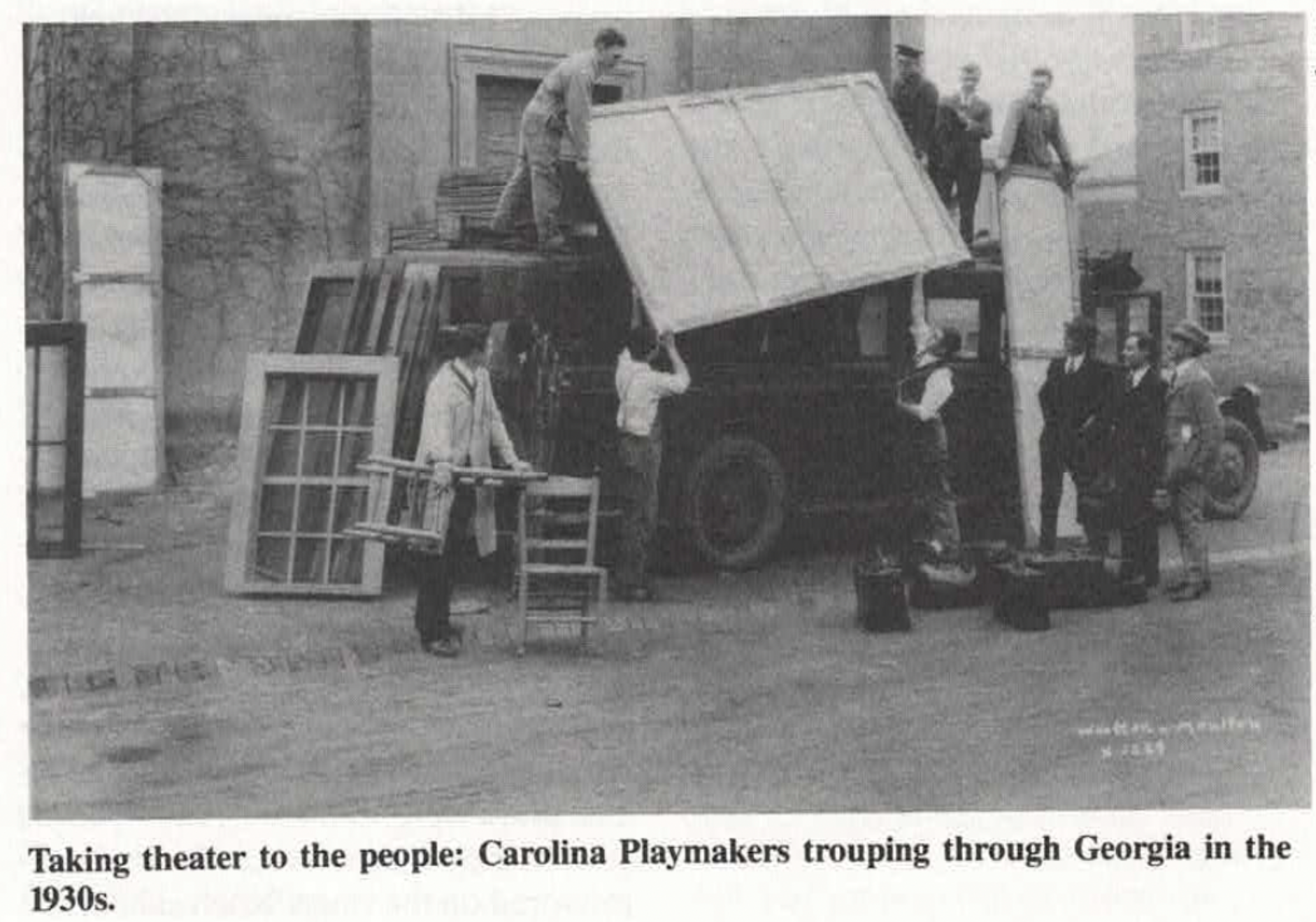

In January of 1919 Professor Frederick Koch gave a lecture entitled ‘‘Playmakers of the People” on the Chapel Hill campus of the University of North Carolina. He stated that the prime purpose of the newly formed Carolina Playmakers would be the production of original plays dealing with North Carolina life and people. The organization would also take responsibility for encouraging such playwriting in North Carolina.

Koch, the visionary director of the university’s drama program, was a Kentucky native. He taught English at the University of North Dakota for several years, and then studied theater at Harvard with George Pierce Baker, one of the most influential theater teachers of the early 20th century. When he went back to North Dakota, he began to produce the Irish dramatists Lady Gregory, John Millington Synge, and William Butler Yeats. He found their plays “of the people” poetic and emotionally direct, and took the “folk plays” concept later when he moved on to North Carolina. The plays were well received — people saw their own experiences and history mirrored on the stage. Koch said of the plays: “Such are the country folk-plays of Dakota — simple plays, sometimes crude, but always near to the good, strong, wind-swept soil. They are plays of the travail and the achievement of a pioneer people.”

Koch had achieved a national reputation by the time he came to North Carolina in 1918. In 1925, when the folk drama movement was only seven years old, the Playmakers Theatre was dedicated on the university campus. It would continue with great vitality well into the 1940s, guided by the belief that the local and specific can serve as a window to the universal — and that, in fact, this is a hallmark of all great art.

The folk drama movement produced novelist Thomas Wolfe and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paul Green, as well as dance critic Walter Terry, performers Sheppard Strudwick, Eugenia Rawls, and Louise Fletcher, bandleader Kay Kyser, Dark of the Moon playwright Howard Richardson, novelist Betty Smith (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and Joy in the Morning), former Wall Street Journal editor Vermont Royster, and others. Many critics of the day felt that the Playmakers’ influence had extended to the novel, to the short story, and to nonfiction. They were described as “a centralizing, crystallizing and vitalizing force unequaled in Southern literature to date.” On the 25th anniversary of the Playmakers in 1943, a noted theater historian stated that “the best way to estimate the significance of the movement known as the Playmakers Theatre is to try to imagine what American play writing would have been for the last 25 years without them.”

When I attended UNC in the early 1970s, only the ghosts of the glory of former times floated through Chapel Hill hallways. As theater students we knew only that we were somewhere that had once been considered important and was no longer. A movement which had lasted more than 25 years was a distant memory — rarely discussed — and described in a standard theater text only by the adjective “influential.”

The UNC drama department in the 1970s seemed primarily interested in producing actors who could read soap opera copy well enough not to make fools of themselves in New York auditions. The concerns of the program had slowly shifted away from what was probably perceived as embarrassingly “regional” to what might be viewed as more cosmopolitan. That meant preparing students for the realities of the world of professional theater — which at that time meant New York and the handful of institutional resident theaters scattered around the country. Remaining in the region in order to create work that might be “valuable” in some way to the overall life of the region was not presented as an option to serious theater students.

The loss of the history of the Playmakers movement is dismaying, especially for those of us who followed along the same path. Because we followed unknowingly, at least at first, we were forced to learn a hard lesson: Without a history it is difficult to enjoy legitimacy in the present moment. So, a grassroots cultural movement like Alternate ROOTS (the Regional Organization of Theatres — South, see article on p.110), which asserts that you can create your own art where you are, out of who you are and what your community is, appears even to itself to have sprung out of nowhere, when in fact it is really just a further step on an already existing continuum.

As a new generation dedicated to folk drama, we now acknowledge the Playmakers as one of a number of historical forebears, which also includes the Chapel Hill-based regionalist movement of the ’30s and ’40s, and the civil rights and women’s movements of the ’60s and ’70s. For us in ROOTS, Southern theater means a theater that is both about the South and for the South — its history and its current concerns (many of which are also national or global). For the most part, we have chosen not to promote organizations that are merely located in the South, organizations whose bill of fare is mostly work written for another place and another time. Our primary interest has been in creating an indigenous body of work which will speak to an audience whose lives and concerns are not usually reflected in mainstream theater.

While fiercely regional, we are not interested in a regionalism that is either quaint or parochial, but one that is expansive in the way that Koch defined it in the early part of the century, and in the way that Kentucky poet, essayist, and farmer Wendell Berry described it in his contemporary essay, “The Regional Motive”:

“The regionalism that I adhere to could be defined simply as local life aware of itself. It would tend to substitute for the myths and stereotypes of a region a particular knowledge of the life of the place one lives in and intends to continue to live in.

“Without a complex knowledge of one’s place, and without the faithfulness to one’s place on which such knowledge depends, it is inevitable that the place will be used carelessly, and eventually, destroyed. I look upon the sort of regionalism that I am talking about not just as a recurrent literary phenomenon, but as a necessity of civilization and survival.”

But can a nomadic corporate culture afford to encourage this kind of attachment to place and to memory? Political philosopher Sheldon Wolin writes: “The major structures of power in this society, whether business, education, finance, the military, government or communications require, as a condition of the effective exercise of power, the destruction or neutralization of the historical identities of persons or places. Persons and places are more likely to survive if they repress their local peculiarities, surrender old rhythms of life and the accompanying skills, and fashion themselves anew to accommodate to the abstract requirements of assembly lines, data processing and systems of impersonal communications.”

The dramatic arts can fit quite neatly into this corporate vision. Devaluing the local, the large-scale “red carpet” institutions produce virtually interchangeable art from city to city and are the perfect cultural components of the corporate society. Priding themselves on an eclectic point of view, these institutions generally present a “well-balanced” season of work. This often includes a piece from the Western European classic literature, a 20th-century American classic, a special event for the holiday season such as A Christmas Carol or a large-scale musical, and one or two plays that were recent successes on or off Broadway, plays like Beth Henley’s Crimes of the Heart or Marsha Norman’s ’Night Mother. The contemporary work produced, whether serious or comic, often portrays neurotic individuals and families, and referred to as “psychological drama.” Rarely is the world beyond the kitchen table looked to as either a source of solace or blame.

There is nothing inherently wrong with these selections. However, the relationship of these theater institutions to the life and concerns of the community as a whole is so limited that even on the rare occasions when they do produce work dealing with important societal issues, they do not do so with the goal of community problem solving, since the liaisons of these institutions are rarely with the health care, social service, educational, or neighborhood sectors of the community.

These theaters do, however, perform a valuable function for the local business community, as they become part of a package of attractions used to lure new business to an area. They provide a service to high-ranking corporate employees and to those who would woo their business. The unwritten law is that they must guarantee an art which will be proficient, and sometimes dazzling, in technical aspects of production, while socially and politically unthreatening in content. Citing their economic impact, these organizations tend to be well supported by municipalities and by local foundations and corporations. Considerable support, both public and private, is therefore going to subsidize the cultural tastes of the most affluent segment of the population. The (often further subsidized) effort of these institutions to diversify the composition of the audience through outreach programs is really only an example of cultural colonization. This attitude assumes the supremacy of the kind of art that those organizations generally produce, in the well-meaning but misguided belief that the only problem to be solved is one of availability of high culture products to all segments of the community.

The “democratization of high culture” is not, however, the heart of the problem. The more critical task is how to promote and support true cultural democracy. Cultural democracy is the right of a community (geographic, ethnic, racial, or sexual) to its own cultural expressions and to equitable access to the society’s material resources for the manifestation of those expressions. However, with the “red carpet” organizations inaccurately viewed as both the norm and the ideal for which to strive, current efforts to sustain an art which promotes a celebration of local culture or a critical examination of local or societal issues have been quite difficult. The goal of this type of work is sometimes to affect a situation directly and sometimes to mirror the history, concerns, and experiences of those not generally included by a theater directed toward the white middle-class.

But the artists who have chosen this path are often denied access to the level of resources available to their colleagues working in mainstream venues. The few progressive funders and publications that do exist often support cultural work that appears at odds with their articulated policies in the social arena, or they fail to support cultural work at all.

If we have any interest, as a society, in building a culture that will reflect the history and diversity of our communities, we will have to understand that “culture” cannot be purchased from Europe or New York. Culture is something we will have to create for ourselves. The extravagant sums of money spent to build lavish new arts facilities have little to do with art and everything to do with real estate.

The living theater artists working throughout the South who are featured in these pages are engaged in a more difficult and more important task of cultural development. Collectively, their work embraces a vision of a South that values both place and past, while maintaining a critical stance toward both the past and present, in an effort to be part of building a future South that will be both humane and just. While it is unlikely that cultural work alone can bring about social change, it can enhance other community awareness and change efforts (See Carol Schafer and David DeWitt’s article on p. 43 about how a play on rape enlightened their community.)

Through documenting the work now being done and by linking that work to its artistic past, we hold out the hope that future generations of Southern artists will see community-oriented work as a valid option. We hope that they will also see that the struggle for cultural democracy, which affirms the validity of art produced and created by a community for itself, is not separate from the effort to build political and economic democracy in the region.

Tags

Ruby Lerner

Ruby Lerner is director of Alternate ROOTS. (1986)