The South Takes a Bow

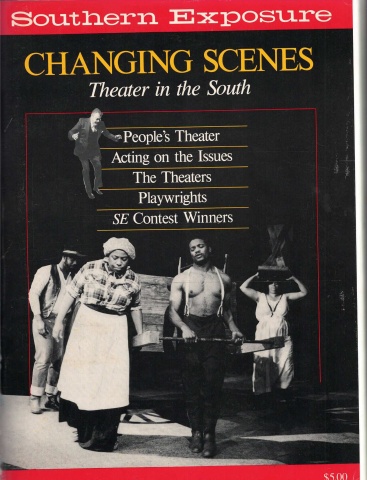

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

It has been a privilege to have the opportunity to document the work of many theater artists who insistently and persistently utilize their art to strengthen, examine, and validate the lives of Southern people. Having always believed that art is a pathway to social change and having personally explored that belief with prisoners, the disabled, and other specialized groups increases my enthusiasm about the significance of this documentation. I have seen changes and empowerment occur through my own experience and through that of many of the other cultural workers examined here.

This issue celebrates the less known — a range of artists whose work is usually close to home, close to people they know best, and close to the heart in a very personal sense. Many of them are people who were deeply involved in the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, the women’s movement, people whose art is very connected to their hopes and dreams for their own lives and world. Many of them remained at home or returned home to practice their art.

Excluded from the issue are the many community theaters, university theaters, and mass culture centers. In general, their choices of plays and broad purposes are a reflection of “high culture” or “Broadway” entertainment and do not speak in particular to a region or to social change issues. While these productions are individually enriching and sometimes important for bonding community members, they are often vehicles to take people away from their own lives into a world that doesn’t exist. Also excluded are the more famous playwrights such as Tennessee Williams and Carson McCullers, because they are familiar to most people and because their work, insightful and beautiful as it is, generally places their characters in deep psychological conflict with limited social/political context.

Some of the artists you will meet are entering a second or third decade of performing, scripting, producing, and touring with shows which illuminate problems and issues pertinent to their close community or ones which explore the broader social issues that perplex and torment society at large. Companies like Roadside Theater draw their material from the history of their communities, examining the rural Appalachian traditions, way of life, and struggles. John O’Neal of the lately-put-to-rest Free Southern Theater had created a character, Junebug Jabbo Jones, who tells stories based on the rural black experience.

Urban groups like Atlanta’s Seven Stages and the Southern Theater Conspiracy examine issues like nuclear proliferation or gay rights or the effects of religious ritual on the form of theater. The play excerpts in this issue reflect the diversity and range of style and subjects from Fred Gamel’s Vietnam Marines on the day of Martin Luther King’s assassination in Wasted to Barbara Lebow’s concentration camp survivor in A Shayna Maidel. Some playwrights tell their own stories in their plays. Others like Jo Carson and Don Baker write about Theodore Dreiser and Stonewall Jackson, famous figures who affected the course of history in small Southern environments. Another performer-playwright, Tommy Thompson, developed his own character, John Profitt, a white man who became a blackface minstrel in the 1840s despite his qualms about the morality of his act.

A play-writing contest designed especially for this issue drew scripts from over 50 Southern playwrights. The two winning plays feature singularly Southern characters, rooted in their communities: North Carolina potato factory workers from Christine Rusch and New Orleans drag queens from Jim Grimsley.

This special issue of Southern Exposure explores the roots of theatrical form as well as the lives and work of the predecessors of the current theatrical movement. There is a blend of first-person narrative and objective journalistic reporting. There are artists who come together through organizations like Alternate ROOTS or the North Carolina Playwrights’ Fund. There is a small directory of grassroots theaters, along with profiles of organizations that fund and support theater, starting points for artists and audiences to make connections. There are also new artists, young artists, people struggling to find a voice that speaks of the present without the experiences of the ’60s or ’70s.

Cultural democracy is at the core of all the work represented here — a culture which speaks of and to the people of a region and about the forces in their lives. Their voices validate the struggle of the oppressed, the underrepresented and the non-traditional. It is my hope that bringing the broad spectrum of cultural work together in this magazine will open new avenues for both the reader and the artists.

It would not have been possible to compile this issue without discussions, advice, and suggestions from Ruby Lerner and Dudley Cocke, who were my consultants. Special thanks also goes to the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation, the J. Arc Foundation, Southern Arts Federation, Bland Simpson, Wanda Cody, and particularly to the staff of the Institute for Southern Studies and Southern Types.

Tags

Rebecca Ranson

Rebecca Ranson is a playwright who is a native of North Carolina. The author of over 30 plays produced in many cities across the country, Ranson bases most of her work on voices of the oppressed. (1986)