This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

The first time I saw a Road Company production was at the Veteran's Administration Theatre of the Mountain Home Hospital complex in Johnson City, Tennessee. In the halffull auditorium were some of the veterans who lived on the grounds.

The Road Company was premiering its company-developed play, Blind Desire. The performance wasn't what I expected to see in East Tennessee. The only set was a giant mobile. Actors dressed in hand-painted costumes chanted about snakes being my soul. Two characters jauntily dashed on the stage and promised to explain it all later. The themes that emerged were political, about our foremothers and about peace.

An old veteran snored behind me. In front of me another old vet spit tobacco juice into a paper cup every couple of minutes.

At the end of the play, the applause was polite. I asked the old vet with the cup what he had thought of the performance. He said he liked it just fine — he never missed any of the Road Company shows. "I would have liked a little more singing and dancing," he added as he shuffled up the aisle.

If Bob Leonard were a realist, he never would have set up a theater company dedicated to new work in Johnson City. While the Appalachian countryside here is beautiful, this city of 40,000 is not exactly a theater center. And 17 regional tours still haven't made the company's existence a practical proposition — most of the places it goes aren't exactly theater centers either. Surviving, sometimes even thriving for more than 10 years has proved that stony realism isn't what keeps the Road Company going.

What keeps it going is the intrepid nature of its founder, producer, director, and at present, entire office staff. Bob Leonard, a native of Massachusetts who studied theater at Wesleyan and Catholic universities, looks the part of the theatrical impresario — tall and thin, with a flowing white-streaked mustache and piercing gray eyes. In spite of the financial problems that stalk his nonprofit theater company, the 42-yearold director is not tempted to abandon his mission of creating original theater. He is not swayed by the gentle suggestions from some pillars of the community that his troupe might do better to stage more accessible productions like 1776 or Annie. Local amateur companies do that sort of thing very well, Leonard thinks. But the Road Company has created nearly two dozen plays, and with its regional tours it has gotten good at ensemble playmaking. Leonard and his troupe are itching to do more.

Honing the craft of creating shows Road Company-style has involved some stormy episodes. Until Blind Desire, serious differences of visions always afflicted the parties involved. The playwright didn't always understand or appreciate what the actors were trying to contribute. The actors weren't always crazy about what the writer was trying to do. And the director always had his or her own ideas.

Somehow amidst this chaos the process worked well enough that some interesting and popular plays emerged: Mountain Whispers and Chatauqua '77; Horsepower and Little Chicago, written by the company and Jo Carson; and Rebecca Ranson's One Potato Two.

Blind Desire was two years in the making and is the company's most fully realized piece, Leonard thinks. The troupe unanimously describes play's development as its most successful and harmonious collaboration, which started in the winter of 1983. Without the restraints of money (there wasn't any) or time (they were all unemployed) the ensemble gathered with the idea of creating something new.

The members already knew each other well. They had toured together sharing motel rooms and long hours on the road. But this was the first time that this configuration of people had tried to invent a play.

Margaret Baker, a Smithfield, North Carolina native, spent a year teaching in the public schools before deciding she didn't fit that role. She went to graduate school and earned her master's degree in acting and directing. After a stint in outdoor drama, she became a member of the Road Company for three years and helped produce her play, The Happy Ever After, a post-nuclear age character

study. Now Baker is a new wave humorist in Philadelphia.

John Fitzpatrick came from Natick, Massachusetts, but he has lived in Johnson City for more than 10 years. He became a member of the Road Company, as both road manager and actor, during the final tour of Little Chicago.

Emily Green is a 28-year-old Nashville native who came to the Road Company five years ago almost directly out of college acting training at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. (She and Baker were classmates.) Because she is a feminist with a playful, absurdist sense of humor, Blind Desire probably reflects her personality more than anyone else's in the company.

Christine Murdock, from St. Louis, represents the third generation of a family of performers. She is the senior member of the acting troupe, with eight years and 17 regional tours behind her.

Eugene Wolf grew up in Tennessee's t Greene County, not far from the Road Company's Johnson City headquarters. When he first joined the troupe three years ago, he knew from his experience in dinner theater that he could handle acting jobs but he had never tried creating characters as he would in the Road Company.

When this group of actors met with director Leonard to begin making Blind Desire, they were determined and ready to do something completely new, something that would incorporate all the techniques they had developed as an ensemble.

First, there were practical matters. To pay the rent on their rehearsal hall, a drafty room above Dave's Hobby Shop in downtown Johnson City, they staged performances of their children's show, the Flying Lemon Circus. The proceeds went to the landlord. Then they got to work.

"We started by talking about what was important to each of us," says Green. She remembers some of the items that surfaced: "Concern for the earth, women's issues, unemployment, being single, Ronald Reagan."

A study of the evolution of religion, When God Was a Woman by Merlin Stone, also stirred the discussions. The book was introduced to the group by Marlene Mountain, a poet, artist, and feminist who worked as the Road Company's secretary until she was laid off when money ran low. Mountain shared ideas and sheafs of her poetry celebrating the goddesses. The actors eagerly discussed the issues she raised.

Bob Leonard knew that a play would not come simply from discussions. "If you talk it to death before you get started, then you can't act it," he says. He got the troupe working — with acting warm-ups, games of motion, improvisations, "sound sculptures," and pantomimes.

"We didn't know what was going to come out of it. But there was an incredible creative freedom — to start from nothing, to start from scratch," says Margaret Baker. She remembers, "I'd come out of those rehearsals so elevated."

Eugene Wolf believes that the job and money crunches that each of the ensemble members had to face forced the group to throw themselves into the effort. "There was a little feeling of despair that went into this show. Things looked really bleak," says the actor.

Green agrees. She believes that now that her life is a bit more comfortable and financially stable, she wouldn't be able to make the same effort. "I think you'd have a hard time getting that kind of work out of me right now," she admits.

The company actors acknowledge that Leonard's best talent is as an editor. He knows how to synthesize, how to grab onto a fine moment and dump the rest, how to put things together so they fit. "He's really good at helping find where freedom can take you, or when you need the discipline of repeating something," says Baker.

The actors also like Leonard's directing style. "Bob lays back and lets things happen. It's much freer for the actor. Most directors tell you what to do," says Green.

Wolf, recalling his work in dinner theaters, nods vigorously. "Yeah, they'll say, 'Move here and say this line funnily.'"

The ensemble members all talk about a technique they developed that winter to preserve the work in progress: the invention of a shorthand that could bring an improvisation back to mind. Leonard explains, "I'd say, 'Rage in a blue room,' and they'd know what that meant. They'd be able to go back to it. Not necessarily the lines, but the feeling, the essence of what was going on."

From the months of rehearsals emerged a wild, eclectic mix of satire, serious political statement, otherworldly costumes and sets — even slapstick.

"Hello. My name is Jean and I need a job,'' Emily Green tells the audience. Behind her, voices try to remind her of her great-grandmother, of her mother, of the ancient goddesses.

Timidly, the unassuming young woman continues talking. She lands a job with a giant company, McMankind, and allows herself to be "made over" so that she will be suited to her new role. "Hi, my name is Jean, and I have a job! Can I HEP YEW?" she shouts happily as she struts across the stage, showing off her newly learned walk. Later, though, after being completely caught up in her life at McMankind, Jean becomes confused. She begins asking questions. Finally she listens to the voices that have been whispering to her all along.

As Jean makes her way as best she can through this absurd, frightening world of the near future, the other four actors play some 30 characters — supervisors, co-workers, a pair of pompous announcers, a bartender, a preacher, and a bridegroom. The choreographed scenes of mindless McMankind routines are interspersed with what the cast calls their "woowoo" scenes, the dream-like dancing, singing, and sounds that are glimmers of the underlying themes.

In its early stages of development Blind Desire wouldn't have been too easy to describe. It was long on the "woo-woo" scenes and short on plot or character development. But all of the issues that the group had outlined as important at the beginning of the creation process made it to the initial

versions of the show.

The cast's editing process started with performances of rough-draft versions of the play at the Down Home (a local bar that usually features music), at the veteran's hospital in Johnson City, and at the ROOTS (Regional Organization of Theaters — South, see articles on p. 110.) annual meeting. The troupe received some muchneeded praise and encouragement, as well as some good advice, especially from their colleagues at ROOTS.

Nearly a year passed before the cast was again able to schedule work on the show. Eugene Wolf describes the process of revision jokingly: "We honed down a little. From 10,000 ideas, we narrowed it down to 2 ,000."

They agreed the story would follow Emily Green's character, Jean. Each actor had specific ideas about what message the play should convey and how forthright that message should be. "There were some pretty major disagreements," Wolf admits. "When it comes to doing a play about women's issues there's a real fine line between serving up the issue intelligently and going overboard and preaching." Their shared purpose kept their disagreements from becoming pitched battles.

Kelly Hill, a former Road Company actor who had moved to San Francisco, rejoined the troupe for the revising process and tour, replacing John Fitzpatrick who had gone to New York.

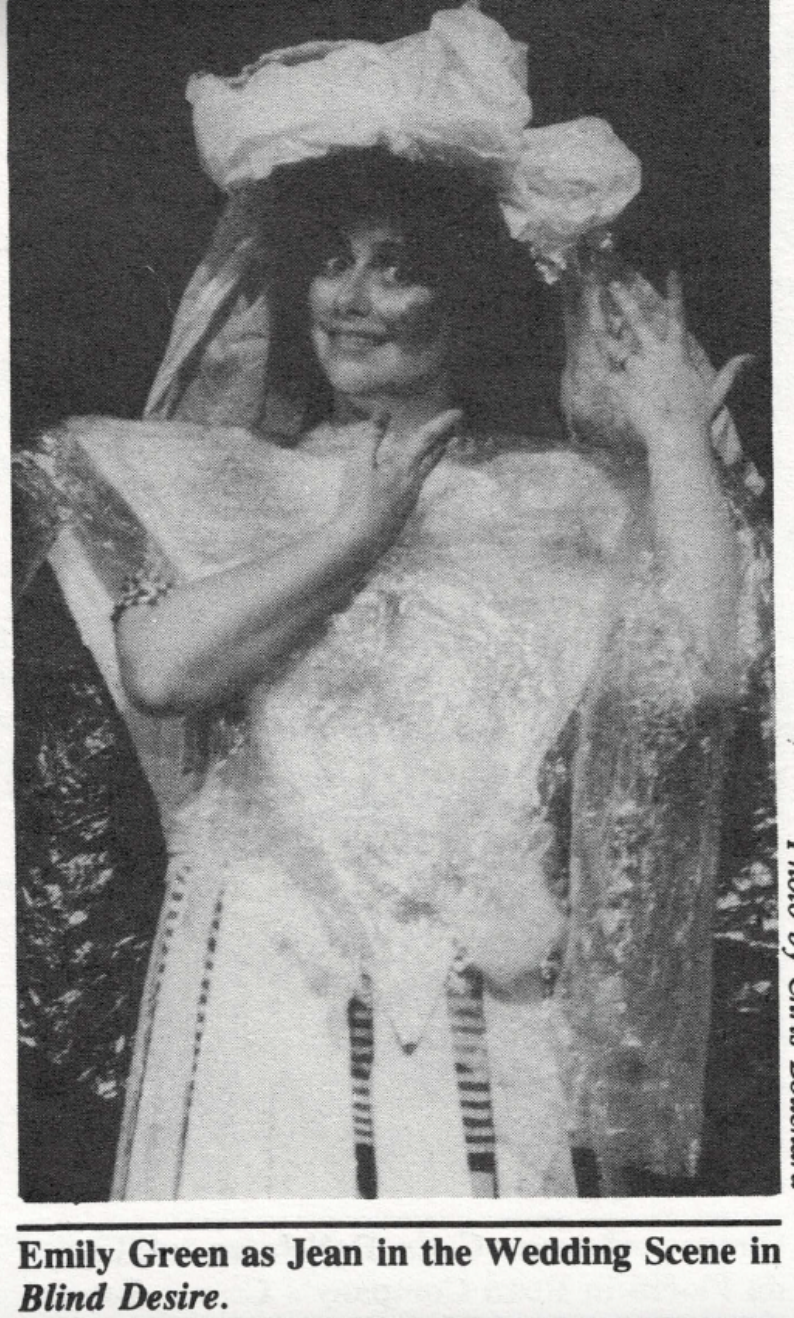

The cast added scenes that put Jean through the paces of womanhood in the 1980s. She works, gets promoted, dates, and marries. In an extravagantly silly wedding scene, Jean steps across the stage wearing a wild cardboard and plastic gown, carrying a bouquet made of a bleach bottle and plastic garbage pail liners. Interspersed with the vows, the minister reels off high tech phrases, and Margaret Baker recites — in a society editor tone — the details of the outfit, ". . . she wore a turn-of-thecentury hat with a waltz-length veil overlapping a full-length veil of lace. . . ."

When the cast decided to invent the wedding scene, it might have been a coincidence that Emily Green had just gotten married. It was no coincidence that Margaret Baker's lines about the wedding gown were an accurate description of her own sister's wedding dress — she had lifted the bit verbatim from the newspaper account.

After an intensive three weeks of revising and rehearsing, Blind Desire became a coherent polished work created by seven authors. In a review in Atlanta's Creative Loafing, Tom Boeker praised how well this "improvisational/ensemble recipe" worked: "Where most theaters succeed in creating avant-garde mud pies, the Road Company pulls off a tight and entertaining, albeit wildly eclectic, show."

Other reviews were equally flattering. Los Angeles Times critic Dan Sullivan called the play "a real winner," and said that "Green plays Jean with real respect, the way Judy Holliday did Billie Dawn." Carl Rauscher of the Atlanta Art Papers said that Blind Desire was "The most impressive play, and the highlight of the [1984 ROOTS] Festival."

While the praise heartened the group and impressed their friends, it didn't translate into busy tours or grants or guarantee full houses. Even after slick brochures went out to every possible customer in the South — from arts councils to university women's studies programs — the fall 1985 tour promotion netted only nine bookings.

This sparse showing reflects a grim trend for the Road Company's tour planning. As funding has shriveled everywhere, fewer of the colleges and arts councils that might have scheduled shows have been able to it. Though Leonard is a good grantwriter, money is harder to find these days and he has less time to look for it. Since 1981 office staff has dwindled from a high of five to the solo operation it is now.

But according to the ever-optimistic Bob Leonard, the solutions seem imminent. Since the tours that used to support most of the Road Company budget are drying up, Leonard and the board of directors are concentrating on gaining more local support. Together, they beat the bushes for money.

They've had to scramble to gather even a modest $84,000 for the proposed 1985-86 budget. The ticket sales, art auctions, garage sales, and mail and telephone fundraising campaigns staffed by volunteers cannot bring in enough to support the company. Government and private grants must still be the basis of the operating budget.

Leonard is always ready to plan new productions on the slimmest promises of funding, not just for the satisfaction of producing the dramas (though there is that), but because the ensemble

members depend on the shows for their livelihoods. Generally, he aims to schedule one or two regional tours a year, a home season of three or four productions, and a playreading series with the work of regional writers.

Last year during the company's home season, it produced a new play by an East Tennessee native, Randy Buck. Adjoining Trances, the story of the friendship between Carson McCullers and Tennessee Williams, featured performances by Jo Carson and Jeff Showman. The ensemble also staged a reading of Carson's newest play. Preacher with a Horse to Ride, based on the writer Theodore Dreiser's disastrous trip to Harlan County, Kentucky during the Depres(see article and excerpts on p. 87).

The Road Company stages repertory work, too. In 1985 the troupe did Jacques Brel is Alive and Well and Living in Paris, Wendy Kesselmen's strange thriller, My Sister in This House, and the musical comedy Gold Dust by Jim Wann.

Yet even when they're doing several plays a year, cast members visit the unemployment lines regularly. The layoffs aren't as grim as they might seem at first glance. Murdock points that work is steadier in this company than in most acting jobs, citing Actor's Equity statistics that the average professional actor earns only about $1,000 a year. While the Road Company members are unemployed more often than they were in the early big-grant years, they still are able to perform more often and make more money than most struggling actors.

There are other advantages for the troupe. The cost of living is much lower in the company's headquarters of Johnson City than in most theater centers. Perhaps most important to the performers is the flexibility. "If there's a play I want to do I can say to Bob, 'Let's do this,' and a lot of times we can do it," says Murdock.

"I would stay here and do this for the rest of my life if I could,'' the actress says. But her long-term commitment and loyalty aren't unconditional. The lack of consistent financial rewards doesn't concern her, but she is upset that because of cutbacks, she has had so little chance to perform in the past year. She is committed to her profession. "I want to act,'' she says simply.

That goal fortifies each of the members of the ensemble. But the Road Company's uncertain future has compelled some of the long-time actors, including Baker and Fitzpatrick, to move to cities where there might be more opportunities. Other former Road Company members have remained in the area, making their living in ways other than acting, and they sometimes rejoin the cast for specific productions.

The small but cohesive arts community in Johnson City and in nearby Jonesborough holds other attractions. "The Road Company has been a catalyst, it's put us together in lots of different fashions,'' says playwright, board member, and local resident Jo Carson.

But beyond the arts community Road Company faces problems gaining local support for its work. Most area residents are natives of southern Appalachia and their lives are centered on family and church, not on the theater. The values and social structures in the area are mostly traditional and at times conflict with the message, or even the existence of the theater. For instance, last year one Road Company fan urged an acquaintance to see Jacques Brel, elsewhere a regularly produced and uncontroversial musical revue. The woman liked the play and was interested in seeing more, but after the performance she got in trouble with her husband for coming home so late.

East Tennessee State University and the Texas Instruments complex in Johnson City bring in the outsiders who make up most of the local audience of the Road Company. But this group cannot always be counted on for support. Some are simply not intrigued by experimental theater, in seeing a work that may have rough, raw parts, or something that might fall on its face because it's a new idea.

Bob Leonard points out that nationally, "No more than 2 percent of the American public goes to the theater. Now, if we were in a theater town, I'd be inclined to play for that already-paying public." But he knows that in most of the small towns where the Road Company performs, even 2 percent of the population won't fill an auditorium for a one-night stand.

He keeps hunting, working on "creating new theater for a new theater audience." Developing Horsepower after holding public hearings and One Potato Two after radio call-in shows were attempts to find and speak to a broader audience. While the plays that came out of those public forums made some successful tours through the South, much of the company's work is just too unusual to attract big crowds.

But Leonard does not back off into the kind of traditional storytelling that is more acceptable and popular here. He thinks that his company can find a new language that will be appreciated. "It might be esoteric in the short-term, but if it's popular it won't be esoteric anymore,'' he reasons.

Discovering a new language that will work is a lot to ask, and while Leonard isn't a pragmatist, he admits that he is sometimes daunted. "It's tough. I don't know what will electrify 50 percent of Johnson City. The problem is, I don't even have access to 50 percent of Johnson City.

Bob Leonard doesn't believe in giving up. Neither do Road Company's actors, writers, and supporters. Jo Carson admires the Road Company's policy of not choosing the safe, more surely pleasing methods: "The Road Company sticks its neck out in a place where chickens get their heads cut off, and that's extraordinary to me."

Tags

Pat Arnow

Pat Arnow, former editor of Southern Exposure and Now & Then, is a writer in Durham, N.C. (1999)

Pat Arnow, editor of Southern Exposure, wrote a play with Christine Murdock and Steve Giles, Cancell’d Destiny, that was featured at a ROOTS festival in 1990. (1996)

Pat Arnow is a writer and photographer who lives in Johnson City, Tennessee. Her short story, "Point Pleasant," was selected "best story" at the Hindeman Writers' Workshop in 1985. (1986)