This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 3/4, "Changing Scenes: Theater in the South." Find more from that issue here.

People helped each other out more. They was neighbors. They didn't bite your back. They talk about this place, but it's ever'where. People don't care about their younguns long as they're out leaving them alone or out stealing. If we'd stole something, my daddy had a belt on our butts taking us to givin' it back.

These words belong to Effie Dodd Gray, one of the three real Atlanta mill village women whose stories are told in R. Cary Bynum's Cabbagetown: 3 Women . . . an oral history play with music.* The

voice is Brenda Bynum's. She has played the part of Effie since May 21, 1978, when Cabbagetown first opened at Atlanta's Academy Theatre under the direction of the Southern Poets Theatre.

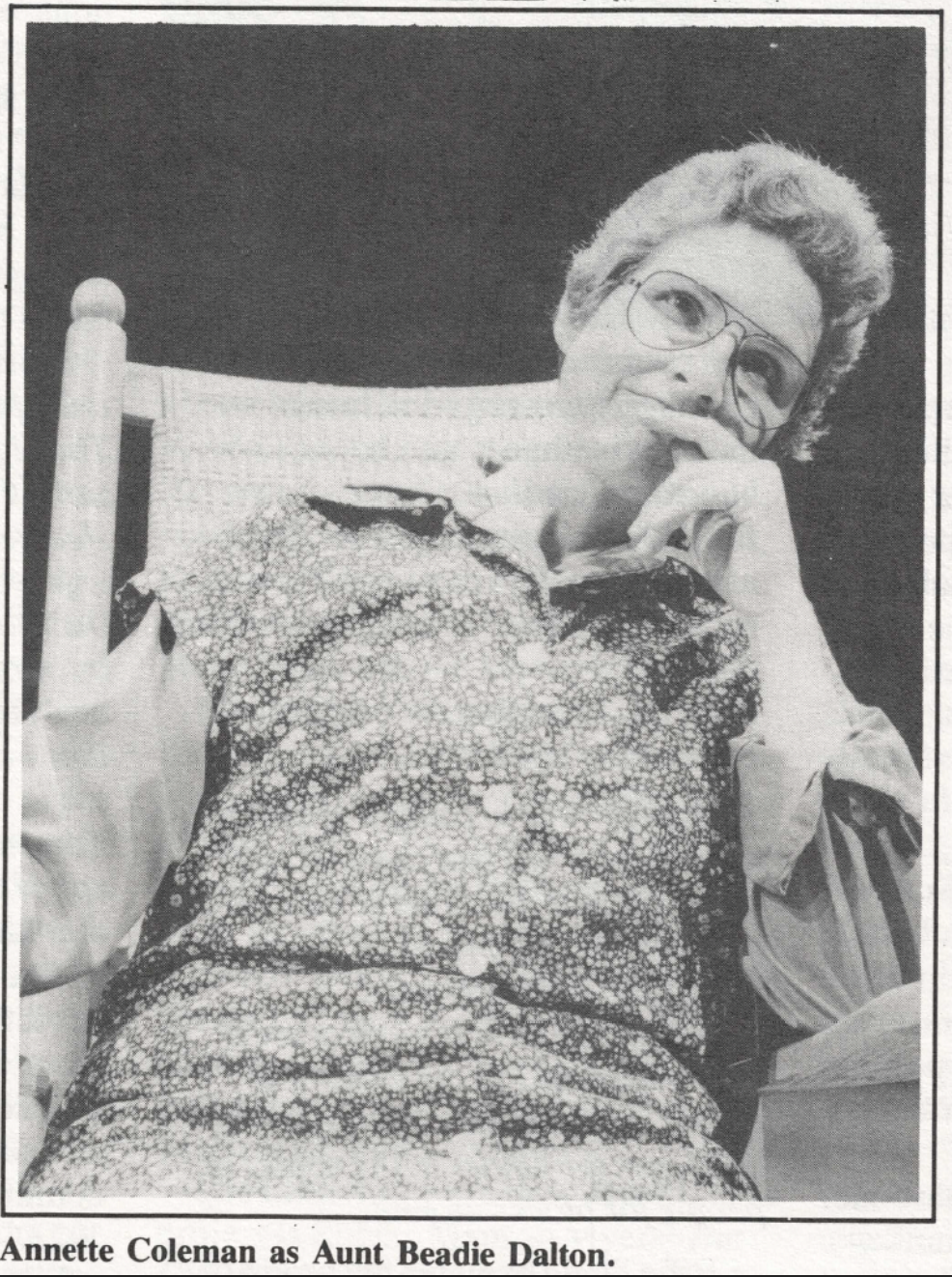

Effie Gray came to the theater to watch "herself' in the play that opening night. So did Lila Brookshire and Beatrice "Aunt Beadie" Dalton, the other two women of the title. At the play's end, the three women stood up in the back of the audience and waved to all the people. They received a standing ovation. Many Cabbagetown people were in the audience; they had come to see their play, to hear other people — actors — speak their words.

Later, the actress Brenda Bynum made a point of seeking out her role's model. "How did I do, Effie?" she asked. Gray replied enthusiastically, laughing, "Lawd God, honey, you do me better'n I do." Bynum was deeply moved by Gray's words, for they confirmed the feeling she had acting Effie in the play, the feeling that the whole theater was in a state of grace that evening. "My God," says Bynum intensely, "I had to think this is where we come from." She meant that she shared Gray's sense of place, a love of where she comes from, a sharing of heritage and rootedness.

This feeling can be powerfully evoked in the theater when a play catches ways of life and deep-seated values and feelings in the words and rhythms of those who speak them. Sometimes theater "does" reality better than reality; it is far more economical and direct. A play like Cabbagetown can reveal to its audience how important and beautiful it is to be human and rooted in a certain time and place.

This enhanced sense of reality is especially true of plays made from oral history like Cabbagetown. Nothing much happens in the play; its power to gain and hold our attention lies not in a plot of contrived events. Its charm rests in the voices, the words, of three mature women of a small village-like enclave within a mile of downtown Atlanta's gleaming, surreal modern office and commercial

towers. The voices weave in out and out and spin yarns, tell funny and sad stories, gossip, recollect old times, give folk remedies and recipes, relate how people felt about other people, recall events at the mill where they worked, tell about their parents and their children, their lean and hard times and their better days. They set forth, in short, a way of life and a set of shared values and beliefs. Cabbagetown is Cary Bynum's most well-known play to date. Its success may owe something to the fact that Cary and Brenda Bynum feel so strongly about their Southern heritage, their roots in Atlanta, the feelings they share with the Cabbagetown women.

Cabbagetown perfectly fleets the Bynums' deep interest in and concern for Southern places and people. The idea for the play occurred to Cary in 1977 when his wife gave him a copy of a paperback cookbook, Cabbagetown Families, Cabbagetown Food.** Pam Durban had put together this little book, now unfortunately out of print, and crammed it with oral history of the Atlanta enclave.

The community's origins, we learn, go back to 1868 when the Fulton Coto Mill was franchised for the Jacob Elsas family. Jacob Elsas was a highly enlightened industrialist of the nineteenth century, a firm believer in the Robert Owen model of community movement.

Owen had worked his way up through the ranks of workers to become owner of cotton mills in his native Scotland; as an owner he tried to spread wealth through a number of social experiments including shorter working hours and improvement of working conditions. He established model communities and sought to eliminate poverty and unemployment through cooperatives and profitsharing plans.

Inspired by Owen's model factory-community at New Lanark, Scotland, Elsas recruited the workers for his new Atlanta mill from sharecropping families in north Georgia's poorest Appalachian counties — Hall, Cherokee, and White. The mill opened in the mid-1880s. For the workers Elsas built houses whose rent was $2 a month for a two-room house considered finer than average by the standard of the time. He provided free medical and dental care as well as a nursery to care for the children of working mothers (the fee was 25 cents per week).

This paternalistic arrangement suited many, although some workers did chafe against the restrictions. The neighborhood was self-contained and very cohesive. The workers' mountain heritage and their economic arrangement gave the Cabbagetown folks a sense of village identity, though the city grew up around them.

The community comprised about 12 city blocks, bounded to the north by the Georgia Railroad. Memorial Drive now marks the southern boundary. The crumbling red-brick mill sits astride the railroad tracks on a site occupied before the Civil War by a steel rolling mill. The population of the community peaked at about 2,000 in 1957.

That year the heirs of the Jacob Elsas family sold the mill to a group of financiers. The new owners had no interest in the village or in Elsas's benevolent ideas. They offered the houses for sale to those who lived in them. Some bought, but most could not afford even a modest purchase price.

"That's when the devil started," says Effie Gray. Gradually, the character of the village changed as new people, not attached to the mill, moved in. Mill work declined during the '70s and in 1981 the mill closed down entirely. Unemployment, of course, brought all its curses: crimes, drugs, violence, loss of pride and of neighborhood identity. The community has wrestled with these problems for two decades now.

Recently, the neighborhood has been fighting off a variety of developers. In 1980, developer Priscilla House formed the Cabbagetown Restoration Society and bought a number of the houses, envisioning an area of fashionable renovated cottages, trendy restaurants, and galleries — a gentrified "gingerbread village," as House put it, less than a mile from Atlanta's downtown skyscrapers. If Cabbagetown's houses are somewhat dilapidated, it still has — in a developer's mind — ideal location and "historic charm."

Old Cabbagetowners, of course, see such developers as a threat to their community. In fact, many older people have been evicted. The developers argue that Cabbagetown's Appalachian heritage is already a thing of the past. Only half of the owner-occupied houses remain in the hands of the

original owners, and very few of the rental properties are occupied by longtime residents. The old-timers, however, say that they need jobs, not new neighbors, and they support a plan by the Seaboard Railroad to use the area as a cargo transfer point. Some of the houses have signs posted on the front porches saying, "We shall not be moved—Cabbagetown." Residents and developers alike wonder what the future holds for the community.

The record of Cabbagetown's past is not in doubt, however, thanks to a number of people who in recent years have made an effort to preserve some of Cabbagetown's rich and interesting heritage by recording its oral history. Pam Durban, a long-time Cabbagetown resident, thought a cookbook might be a way to record oral history and make some money for The Patch, a group originally organized to provide a center for young people aged eight to 16. Now directed by Esther LeFever, The Patch also serves as a community action group. The Cabbagetown cookbook turned into much more than a cookbook. Cabbagetown Families, Cabbagetown Food is a unique composite of community chronicle, oral history, and recipe collection. Among other things, the book explores the two main

theories explaining the origin of the community's name:

Maybe it was because a produce truck overturned and dumped cabbages all over the street so that people ate cabbages for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for days afterward. Or it might have been because a person standing in the window of Fulton Cotton Mills could smell the cabbages for dinner in the homes of people for blocks around.

Effie Dodd explains the origin of the name this way:

The Veteran's Cab was the ones that started it when they come back out of the service. They called over there around Bellwood the Black Bottom, and they called out there around Grant Park the Salad Patch, and over there around the Fox Theater it was Collardtown. They had each section named. But really what got it to going was when old lady Keel opened this place up here on the hill, the Savannah Street mission. And to get donations and everything, she had pieces wrote in the paper calling it Cabbagetown.

However it got its name, Cabbagetown gives most people a special feeling, and the cookbook — not to mention the Bynums' play — conveys that feeling by letting the people speak for themselves:

You could go all over the world, and you can't find a neighborhood like Cabbagetown. Most of our people are very proud.

They're poor and they know it, but they hold their heads up.

There really is a closeness here, a togetherness that is hard to find in other places.

The cookbook is divided into sections, each headed simply by its author's name. "Beatrice Dalton,"

"Lila Brookshire," and "Effie Dodd Gray" comprise the opening three and longest sections. Each woman talks about her life and gives a recipe now and again. Aunt Beadie's section opens this way:

I was born out in the country, called it the piney woods where I was born. The night I was born, there was a blizzard. Coldest night, Mama said, just sleeting and snowing. A man and his wife was moving from Dallas, Georgia back up to Polk County and they come by our house. They moved in a wagon and they had all their belongings on that wagon and it broke down. It was awful cold. My daddy went down and he invited them up to the house to spend the night and so they was there that night.

She continues to reminisce about her father, who was half-Indian, about chopping cotton and preserving and preparing food, about kinfolks, about sickness and folk remedies, and about coming to live in Cabbagetown in 1923.

Lila Brookshire tells her story and then philosophizes a bit:

They's been some wonderful people that's growed up here and ventured out and made something of theirselves. I think that's the biggest problem is people if they want to make something of theirselves. Mama always said you could be a lady and work anywhere and I found that to be true. I mean I was treated nice. I never had no trouble in the mill.

When the Bynums first saw the cookbook, they immediately spotted the dramatic possibilities in this material. Cary Bynum telephoned the people at The Patch for permission to adapt the book into a play. He talked with Harriet Treadwell, among others, who told him about Joyce Brookshire (Lila's daughter), a folksinger who had ready written songs about Cabbagetown. He decided right away that her music would fit perfectly into the play. The stories in the cookbook "simply knocked me out," says Cary Bynum. Brenda Bynum agreed: "My God, this is where we come from." Neither had grown up in Cabbagetown, but they identified with the strong sense of place, the roots, the Southern heritage, the strong sense of values.

Now in their 40s, the Bynums had almost lost their Southern identity in their youthful quest for theatrical success. After they married in their native Atlanta, they had moved to New York City, aspiring to the professional theater. During the first part of their 10-year sojourn in the city they tried to live and think like New Yorkers. "The place to go in the 1950s and 60s if you wanted to work in the theater as a writer or actor was New York," Cary Bynum says. His New York period brought him success. His play Sherwood, an absurdist treatment of life in the city, was produced off-Broadway. Monkey Palace, on the same theme, was produced at the prestigious Circle the Square.

To support himself and his wife and their growing family, Cary Bynum managed a bookstore near Carnegie Hall and then worked as an editor for the publishing firm of Holt, Rinehart and Winston. The job paid the bills and gave him the opportunity to work with the language. Brenda Bynum

served as an assistant to a musical director who composed and produced shows and commercials for television. She also did freelance editing and proofreading for several publishing firms.

While they lived and worked in New York, an astonishing change occurred for the Bynums: they discovered their Southern roots. For one thing, the birth of children made the Bynums realize that they wanted their children to grow up in the South. But they also came to realize that the South had a great literary tradition — Thomas Wolfe, William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren — and they began reading Southern writers. They became enthusiastic about the Fugitive-Agrarian movement that was generated at Vanderbilt University in the 1930s by poets and writers such as John Crowe Ransom. They wanted to find ways to develop theater in the South, in their home.

"Incredibly," remembers Cary Bynum, "the Southern Poets Theatre was conceived on the Lower East Side of New York." The Southern Poets Theatre became the Bynums' instrument for developing and presenting Southern writing, Southern values and beliefs and ways of life, and Southern speech. Brenda Bynum says, "Whenever something presents itself that needs to be done, we do it."

The theater group's most recent project is Robert Manson Myers' The Children of Pride, a cycle of five plays based on Myers' 1,900-page epic The Children of Pride, a compilation of letters written by the members of the Charles Colcock Jones family of Savannah, Georgia, between 1854 and 1868. The Southern Poets Theater presented the entire cycle in Savannah last October under the auspices of the Georgia Historical Society. Brenda Bynum served as executive producer and her husband as artistic director.

"In everything [the Bynums] do, whether it's Cabbagetown or The Children of Pride, they focus on the South, on roots, on family, on the decency of human beings," says Helen C. Smith of the Atlanta Constitution. "They always find the strengths of the people they're writing about. They have an almost spiritual dedication to that."

Since the couple's return South, Cary Bynum has written several plays, all of them exploring Southern materials arid themes. A Late Rain, for instance, has a Fugitive-Agrarian theme. The plays he has chosen to direct for the Southern Poets Theatre reflect this interest in Southern materials. One of his more successful pieces was The Chinaberry Tree, a selection of readings from Georgia poets.

In putting the Cabbagetown play together, "we went into homes," says Brenda Bynum, and "just talked." "We didn't want to exploit people or invade their privacy," adds Cary Bynum, "and we didn't know if we could make this material work as a play. But I was drawn to the material — it was Southern. And I recognized in the speech of the people a poetry — Effie is a poet — that I wanted to explore." Cary Bynum compares the speech rhythms of Effie Gray and the others to the "prose poetry of Eudora Welty." The difference, of course, is that Welty's folklore derives from the rural South, whereas that of Cabbagetown represents once-rural Southerners who moved to the

Southern city in the last century and so have been exposed to the pressures of urban life.

In building the play from the oral history of the cookbook and that which he and his wife gathered — sometimes on tape — Cary Bynum exercised principles of selection. By discarding some material and emphasizing others, he enables the characters to "build themselves." This procedure, he explains, "allows a more natural character development than to impose or contrive speech. In other words, I let the characters speak for themselves. The characters are shaped from their own materials. That's my concept of oral history theater. I arrange or orchestrate the material, which is some of the best oral history I've seen. All I did was put it into dramatic form.

"I believe this process allows a revelation of real character, an outpouring of the real self, though it involves leaving out a good deal of material. What I wanted to do was put the audience right there on a Cabbagetown porch talking with those ladies. What's interesting is the alchemy of the city on the Cabbagetown people. The dialogues of the people show them evolving from their life on the land through their city life. They have something unique."

The play does indeed put the audience on a Cabbagetown porch, listening to Beadie, Lila, and Effie talking. The set is simplicity itself: a front porch and yard in Cabbagetown in the spring of 1975. A porch swing at center stage, two stools right stage, a cane-back rocking chair, and a worn metal glider chair on the left comprise the setting, along with some plants in coffee cans, hanging in baskets by rope or chain. The women move sparingly about the simple set. Just as in the book, they reminisce about the past, gossip, spin old yarns, give home remedies, let us peer into their lives in Cabbagetown and their childhoods on the north Georgia farms. One story elicits another. There is little dialogue and no plot or story, though there are many stories, monologue following monologue. The voices convey an authentic sense of the lives, the values, the fierce pride and independence of the women. Here, for example, is Effie telling us why she has never voted:

When Roosevelt was going back in there for the second term, they would take us up there to vote. That old smart aleck was filling out my papers and asked me: "Well, who's the governor?" I said, "Talmadge." I knowed all that, I just couldn't read and write. And she said, "Well, who's the senators over Georgia?" "Russell's one," I said. "I can't think right now who the other one is." "Well, I don't see how your vote'll count anything," she said. "Lady, I'm gonna tell you something," I said. "You see them papers?" She said, "You have to sign them." I said, "Uh-uh. I might sign them for Roosevelt and Talmadge and Russell. But you probably have somebody else's name on them. You just take that paper and tear it in two and ram it up your butt!" And I walked out. They were saying, "Go report her, go report her, she ain't supposed to talk to you like that!" I said, "Well, he's going to get it anyway, he don't need my vote." I ain 't ever voted. There's two things I don't do — that's vote and sign petitions.

Then Lila responds with:

I don't know how many different people lived in this house with us on Reinhardt Street; and I never had no trouble except with one, and she kind of got jealous of me and her husband, which she didn't have no cause to. She brought out a word one day — when me and him was standing out on the porch looking down at the kids. She brought out a slur, and I didn't do nothing. I just went to the door, and I told her, "'You jealous of me, you can forget it. I wouldn't have another man under the shining sun except my husband." She apologized later. [Sits on swing beside Aunt Beadie]. I reckon everybody thought a lot of me. If I've got any enemies, I don't know about it.

We hear stories of hard work and lean times, embarrassing and funny anecdotes, episodes of alcoholism, betrayal, religious salvation, death, as well as marriage, birth, and deep religious feelings.

One of the play's strongest features is the music — seven songs dot the text — some of it by Joyce Brookshire. Her moving ballads, like "Cabbagetown Ballad," contribute importantly the tone and imagery:

We came to Cabbagetown in eighty-five

To work in the new cotton mill;

For we had heard the pay was good, There were many jobs to fill.

We said good-bye to our mountain homes,

There to return no more;

But we brought with us a way of life

That we had known before.

We're a mountain clan called Cabbagetown

In the city of Atlanta, G.A.

And if it be the will of God,

It's where we'll always stay.

The play is also sprinkled with traditional mountain tunes and old hymns played on guitar and

Harmonica — "Will the Circle be Unbroken," and "I'll Fly Away." Joyce Brookshire herself played and sang in the production, accompanied by Fritz Rauschenberg.***

Since 1978, when the Bynums' Southern Poets Theatre opened the play at the Academy Theatre, Cabbagetown has played Atlanta intermittently. The three roles were originally played by Brenda Bynum, Doris Bucher, and Annette Coleman, all professional actresses. Its popularity is unrivaled in Atlanta theater, and reviews have been almost unanimously enthusiastic. Atlanta Constitution critic Helen Smith in 1978 called the play a "theatrical event of note and of high promise, . . . simple, effective, and moving. It worked beautifully, in a low-key, very human way." Scott Cain, writing the same year for the Atlanta Journal called it a "warm and wonder ful theatrical experience, . . . simple as pie and just as satisfying, . . . charming and friendly." Later that year Joseph Litsch commented in the Constitution that the play's concerns really supercede the Cabbagetown neighborhood and that the play "touches the lives of almost anyone swept along by urbanization." As the play has continued to be produced, critics have continued to analyze it. In 1984 John Carman remarked in the Constitution on a local televised version of the play: "You'd have to be from Saturn not to appreciate the durable mountain strain that took root next to the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill." Ernest Schier, director of the National Critics Institute, was quoted as saying, "This fine piece has great potential for a good off-Broadway house."

Whether Cabbagetown ever makes it to off-Broadway seems beside the point to its most enthusiastic audience: the Cabbagetowners themselves. Over the years they have flocked to see their play, to watch other people speak their own words. Cary Bynum says that the play astounded and excited them, especially the three women themselves, who have been delighted. Joyce Brookshire says that she cannot get through some parts of the play without crying. "This is just something really special to me," she remarks, shaking her head and smiling. She mentions especially the part where her mother's character Lila talks about Joyce's father leaving home:

I came down here around '32. He, my husband, took to rambling, so I guess that — off and on — we stayed between here and Gainesville [Georgia] for 12 years. Load up and go to Gainesville, and they'd get tired of us up there, and we'd have to come back here again. Joyce, the fourth child, she was born in April and about June, that's when he left.

Then in the play, the folksinger Joyce sings "The Orchard Song ":

My daddy left home early one morning

Said I'll be back as soon as I can

I'm going to Carolina to get a load of apples

We never saw my daddy again.

How long does it take to grow an orchard

And pick all the apples one by one?

Twenty-nine years is a long growing season

And I guess that's the reason my daddy's still gone.

"What the play taught me," Joyce Brookshire confesses, "is that I have real feelings about my past, my heritage." She explains:

"I always knew I loved Cabbagetown, but the play gave me a special feeling about the place. Since the play I've talked a lot more with my mother about the past. It's very important to keep our past, to preserve our oral traditions, to tell how things were and who we are."

Brookshire's deep feeling recalls Effie Gray's words to Brenda Bynum:

"You do me better'n I do." The effect of a play like this reaches far deeper than entertainment or diversion. As Brookshire says, it helps us to understand "who we are." It explores roots and identity.

It may do even more. If Cabbagetown survives the onslaughts of the developers as an Appalachian village displaced to the city, it may well be that this play provided inspiration and gave hope. If the community goes under, at least the play survives as a living record of what life there was like, as a chest full of warm memories, and as a reminder of values carried from the hills: "Mama always said you could be a lady and work anywhere, and I found that to be true."

Notes

* (Foxfire Press: Rabun Gap, Georgia, 1984).

** (Atlanta: Patch, 1976).

*** Joyce Brookshire's three songs for the play — "Cabbagetown Ballad," "How Long Does It Take to Grow an Orchard," and "North Georgia Mountains" — are printed as music with the text. A wider selection of Joyce's music is available from Foxfire Records as "North Georgia Mountains."

Tags

William French

William French is an associate professor of English at West Virginia University. (1986)