This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

"Favorable business climate" and "ideal places to live" are regularly assessed, but there have rarely been indexes of good places to work. Indeed, the criteria used by most business climate reports — like Grant Thornton's General Manufacturing Climates — assume that low wages, limited unemployment compensation and worker protection, and weak unions are good for business. This is a strange assumption for people who also profess to believe that people are our most important asset. The Climate for Workers report we prepared for the Southern Labor Institute demonstrates the error in this traditional assumption.

We believe that the true test of economic conditions is how working people — the vast majority of citizens — fare in these times of economic change. After analyzing 33 indicators measuring income, job rights, health and safety, equal employment opportunity, and job loss benefits, our study revealed that workers in the Southeast, more than in any other region, fail to enjoy the full fruits of their labors.

For example, the Southeast's extraordinary growth in jobs between 1975 and 1984 has been accompanied by the least change in personal income of any U.S. region. While four Southeastern states rank among the top nine in job growth for this 10-year period, eight Southeastern states fall among the bottom 11 in personal income growth during the same years.

The Southeast gained 5.2 million jobs between 1975 and '84, a 32 percent increase.

More and more people are working full-time year-round yet have incomes below the poverty level. These are the working poor. Working people are much more likely to be poor in the Southeast than in any other U.S. region. Of the 10 worst states, eight are in the Southeast — ranging from Tennessee, with 8.2 percent of its workers below poverty level, to Mississippi at 12.7 percent (the highest proportion in the nation).

In all 12 states of the region except Virginia and Louisiana, over 70 percent of the families with incomes earned less than $25,000 in 1979. Southeastern states still have the lowest per capita incomes in the U.S., and nine of the 12 Southeastern states are among the bottom 13 in manufacturing wages, averaging less than $8 per hour. The range in these states extends from $7.97 in Alabama to the national low of $6.95 per hour in Mississippi.

The Southeast can rank high in job growth while also ranking low in wages and income, because in eight of the Southeastern states more than 40 percent of the manufacturing jobs are in low-wage industries (those with national average wages of less than $8 per hour). These include lumber and wood products, furniture and fixtures, food and related products, textiles and apparel, rubber and plastics, leather and tanning, and miscellaneous manufacturing jobs.

The eight states range from North Carolina, with 62 percent of its industrial jobs in low-wage industries, to Virginia with 40 percent. Only Kentucky, West Virginia, Louisiana, and Florida fall outside the 40 percent threshold in the study.

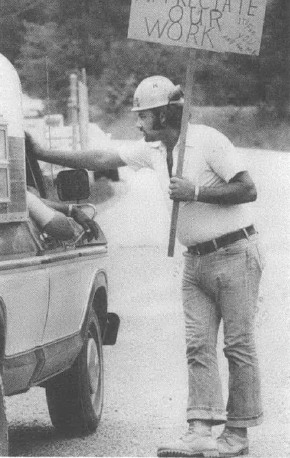

Worker's Rights

Not surprisingly, the eight states in the nation with the least worker protection are all in the Southeast. When it comes to state statutes and labor department policies governing the workplace, protecting workers' rights and safety, and providing compensation for disability and unemployment, the South falls considerably below all other U.S. regions. Briefly, these are laws prohibiting sexual harassment, electronic surveillance, and discrimination; laws providing whistleblower protection, access to personnel files, maternity leave, and time off to vote; laws establishing minimum wages, maximum hours, mandatory pay for overtime, timely payment of wages, and equal pay by sex; and laws guaranteeing employees' right to know about exposure to hazardous materials on the job and to obtain information about their welfare funds.

In Alabama and Mississippi, not one of the 14 laws had been enacted; in South Carolina, only one; in Virginia and Louisiana, only two; in Tennessee, Florida, and North Carolina, only three. The other two states in the bottom 10 are Iowa and North Dakota. California lacks only legislation prohibiting electronic surveillance. The other states in the top 10 — those providing the best statutory protection for workers — are Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Illinois, Ohio, Alaska, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Maryland.

While all states provide disability benefits for job-related injury, there is considerable variation in the maximum weekly benefit. At the bottom of the benefit scale, five of the six states that pay the least for permanent total disability — under $200 per week — are in the Southeast. In the nation's 12 worst states, the weekly unemployment benefit is $140 or less. Eight of these twelve are in the Southeast. At the bottom is Mississippi ($105).

Until recently, blacks and women have been excluded from traditionally white male occupations, such as officials/administrators, professionals, technicians, and craft workers. Southeastern states rank on the bottom in the percent of working blacks and women employed in these jobs.

There are in effect two Souths: one where jobs and income are available, and one where they are not. The poor, the working poor, minorities, and women — especially in the rural South — have formed a permanent underclass in the region, one that has been called "disadvantaged" and "structurally unemployed" for more than 20 years.

With recent changes in federal policies and programs, the lot of this underclass has deteriorated below even the poverty levels of the early 1960s. Given the climate for workers in the region, this group of citizens has few options for helping themselves. In the absence of policies and programs that directly address their needs as workers and income producers, there is little hope that help from other sources can make a lasting difference in their lives.

Tags

Kenneth Johnson

Kenneth Johnson, former regional director for the National Rural Center, is the director of the Southern Labor Institute, a project of the Southern Regional Council (SRC). (1986)

Marilyn Scurlock

Marilyn Scurlock is a staff member of the institute and former staffer with the National Rural Center's Southern office. (1986)