This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

Any honest look at the data describing the South's economic condition reveals the dilemma in which the region finds itself. On the one hand, many of the South's cities are prospering, attracting new capital, new residents, and new jobs. On the other hand, many of the its rural communities, which took in low-wage manufacturing plants with the understanding that they would eventually be replaced by new industries with better jobs for local citizens, are faltering. The new, high-paying jobs have not arrived, and the branch plants that once flocked to the South for lower labor costs are now moving out for still cheaper labor overseas.

As William Winter, former governor of Mississippi, told an audience of Southern officials and citizens at a Southern Growth Policies Board conference in Birmingham in January 1986, "There remains that other South, largely rural, undereducated, underproductive, and underpaid that threatens to become a permanent shadow of distress and deprivation in a region that less than a decade ago had promised it better days."

The present condition of the South's economy was not anticipated when the 1970s were fading into history. Working with the 1980 Commission on the Future of the South, economist Bernard Weinstein wrote, "In the seventies the South was the fastest growing region and the rural South was leading the way. Indeed the nation's fastest growing counties are now in nonmetropolitan areas; and this is true in the South as well . . . industrial growth is filtering down to small towns and sparsely populated counties." Just five years later, however, Weinstein wrote without apology in a Wall Street Journal editorial that "the Sun Belt has collapsed into only a few 'sunspots.'"

Just what is happening to the South's economy? Has the blossom left the rose or is the South simply consolidating its gains and regrouping in response to more intense international competition? How is the South's economy realigning itself? Who is getting what kinds of jobs in the emerging economy? What can we do to prepare for the future, to improve opportunities for those adversely affected, and to provide opportunities for those who have not yet made it into the mainstream?

Branch Plant Daze

Over the last couple of decades, economists have heralded the convergence between the South's economy and that of the rest of the nation. The exchanges of people and jobs among regions gradually have homogenized both the industrial and occupational mixes in the South so that they are now quite similar to the U.S. averages. But there are a couple of notable exceptions. One is a stronger concentration in the South of jobs in nondurable manufacturing industries. The other is a heavy dependency of Southern rural communities on manufacturing.

Both are residual effects of the unique way in which the South transformed itself from an agricultural to an industrial economy. The South essentially gave up on farming long ago as an economic strategy to sustain its large rural economy, and accepted the fact that the decline of farm employment, in the long run, was as inevitable as technological progress. Between 1977 and 1982 the number of acres farmed in the South decreased by 30 percent. Further, land loss by black farmers was two-and-one-half times more rapid than loss by white farmers.

Instead, the South based its development strategies on the acquisition, by whatever means necessary, of existing or expanding businesses. The industries most likely to land in the South were those that produced nondurable goods, such as textiles, apparel, and processed foods. Jobs in these highly labor-intensive industries required less education and less skill than jobs in most other industries, and the South had a surplus of relatively low-skilled people ready and willing to leave the farms and go into the factories. The popular development tactic in the South during the transition from agriculture to manufacturing was industrial recruitment, and states and towns creatively and aggressively packaged incentives to attract employers seeking new plant sites. The rural South, with its low-wage, nonunion labor force and willingness to "give till it hurts," became an active and frequently successful competitor in the "jobs war."

As a result of three decades of "winning," the rural South is more dependent on manufacturing for its jobs and income than any other region of the country. About 27 percent of all jobs in the rural South are in manufacturing, compared to only 18 percent of all jobs in Southern cities. But with too many of the plants lacking unions or enlightened management, wages remained low and working conditions poor. Thus, a large share of the rural industrial workforce has traditionally consisted not of heads of households but of members of farm families trying to keep marginal farms active, as well as wives trying to supplement their husbands' meager incomes and raise their standard of living.

More and more of the income of farm families comes from off-farm employment. In 1963, 60 percent of all farm family income came from farming; in 1983 only 29 percent of farm family income came from farming. And in the South, farmers work, on average, more days off the farm than in any other region. Poor farmers, however, are less likely to hold off-farm employment according to a recent study of farming in North Carolina. Further, in Southern rural areas it is more often women who get the factory jobs. More than 26 percent of rural employed females work in manufacturing, compared to about 14 percent of working women in cities.

Unrealized Dreams

The economic development strategies that brought the so-called rural renaissance, however, have been achieved at a cost. Many of the same conditions and attributes that attracted branch plants also kept wages low. Despite the number of new jobs created, per capita income in the rural South was only 74 percent of that of the urban South in 1980, and the per capita income of rural blacks was less than a third of the urban South's per capita income (which was about at the national average). In mid-1985, average hourly production wages in the South were $8.07, 16 percent below the average for the non-South, $9.57.

Working women, according to the 1980 census, earned less than working men and blacks earned less than whites. For every dollar earned by an average full-time worker outside of the South, inside the South the white male earned 92 cents, the black male earned 53 cents, the white female earned 53 cents, and the black female earned 47 cents. In addition to the low wages, because of low taxes and an aversion to social programs, the rural South spends less on public schools, has fewer dentists and physicians per capita, and has high functional illiteracy, high infant mortality, and shorter life spans than other regions.

In the 1980s, the profusion of jobs generated by the influx of branch plants ended abruptly when the recession, underscored by a strong dollar and increased foreign competition for jobs and markets, struck manufacturing. It hit nondurable manufacturing, the heart of the South's rural economy, particularly hard. As competition heated up, Southern communities simply could not compete on the basis of what was formerly their biggest advantage — low labor costs, which are still well above costs in many other countries. At the end of 1985, the unemployment rate for the region stood at 8.5 percent, 2.6 points above the average for the non-South.

At the same time, the agricultural economy also is being reshaped. Falling land prices, tight money, diminishing foreign markets, and loss of off-farm employment are taking a heavy toll of the small and medium-size farm. Between 1981 and 1985, farm land values in the South fell dramatically. During the ten-month period from February 1985 to April 1986, the average value per acre dropped 20 percent in Louisiana, 17 percent in Arkansas and in Texas, and 10 percent in Mississippi. The number of farms in the South declined by 12 percent between 1975 and 1985.

Those who believed — or hoped — that high unemployment rates were temporary phenomena of a strong dollar, an unbalanced budget, and a recession are finding that the causes are much more basic and possibly permanent. Even though the South in total gained 3.8 million jobs between 1977 and 1983, many of the places that lost large numbers of jobs have not recovered. At the end of 1984, employment in textiles was only 83 percent of what it had been in mid-1977; between 1980 and 1985, 250 textile plants closed and 248,000 jobs were eliminated. No one seriously believes that the textile industry will regain its previous levels of employment.

Even the so-called high-tech industries (a definition based on size of investment in research and development and number of technical employees) proved to be unstable once their products matured to a mass-production stage with the potential for large employment. Electrical and electronic equipment industries, which include many high-technology components and products, lost 68,000 jobs in the U.S. last year. Plant closings and major layoffs in the past year include General Electric in Kentucky and Virginia; Burroughs, Motorola, and IBM in Florida; and ITT in North Carolina. Further, employment in high-tech industries constitutes only about six percent of the nation's work force (every Southern state is below that national average) and wages are not necessarily higher than those in traditional industries.

• From January 1979 until January 1984, 1.5 million Southerners were displaced from their jobs — more than half in manufacturing.

• In January 1984, one-third of all those displaced had been out of work for at least half a year. Because wages in nondurable manufacturing were so low, three out of five workers in those industries fortunate enough to find new jobs now make more than they did before — but still not enough. In 1986, the average wage for retail jobs, one of the largest sources of new jobs, is well below the poverty line for a family of four.

• In December 1985, four Southern states still had double-digit unemployment rates. Only three Southern states — North Carolina, Texas, and Virginia — had rates below the national average.

• Average unemployment rates for 1984 for the nonmetropolitan counties was in the double digits in six Southern states.

• The increase in per capita income in the South during 1984 was less than the U.S. average increase of 5.3 percent for every state except Virginia. The per capita income for the Southeast was 13 percent below the U.S. average and the lowest of the eight U.S. Commerce Department census regions.

Microchip Mania

Official hopes for stemming the decline in manufacturing and securing a sound production base for the South's economy are pinned on innovation and technology. Even where successful, however, technology is unlikely to reverse the pattern of increasing concentration of jobs in service industries and therefore in cities. In an automated Burlington Industries plant in Cordova, North Carolina, which once bustled with workers, one person now can handle as many as 25 machines. Taking technology one step farther, flexible manufacturing systems, which move material from one station to another, eliminate even material handlers and setup people.

Richard Cyert, president of Carnegie-Mellon University, claims that the only way the country can save its manufacturing sector is by using new technologies to reduce employment in manufacturing to 10 percent of the nation's work force, compared to 21 percent today and 27 percent in 1970.

As the shape of the South's economy changes, the conditions that encourage economic growth change too. An adequate supply of low-skilled and compliant workers is not such an important attraction to the emerging growth businesses; they are more dependent on technical expertise and innovation than on manual dexterity. And today low taxes, inexpensive land, and industrial services are not as important as proximity to airports, technical assistance, and telecommunications networks to businesses more concerned with the flow of information than the flow of goods.

Past neglect of human resource development and human services in the South in general, and in rural areas in particular, is taking its toll on the economy. Only half of all rural adults in the South have completed four years of high school, and today every state in the South has a higher dropout rate than the national average. Fast growth businesses, many of which utilize or produce information or technological products, prefer to operate in or near sizable cities that have a work force with higher levels of education, transportation, and communications linkages, and a choice of public and private services. Most rural communities lack all these prerequisites.

Employment data for the South illustrate the realignment of new jobs from manufacturing to service industries and from rural locations to urban centers. Despite the reductions in manufacturing jobs between 1977 and 1983, total employment in the South grew by 22 percent in metropolitan counties and by 11 percent in rural counties.

Growth in the South was due largely to increases in employment in services. Consumer services, for example, which include service stations, eating and drinking establishments, and retail stores, accounted for nearly two-fifths of employment growth. Southern counties that grew the fastest between 1977 and 1982 were those with the largest portion of their jobs in services (60 percent). The counties that grew the slowest had the smallest proportion of their jobs in services (38 percent). While growth in service employment is putting more Southerners to work, it is not doing a great deal to raise median income. In retail services, for example, in 1980 the median income in the South was $13,500 for a white male, $7,300 for a white female, $10,200 for a black male, and $6,900 for a black female. In food preparation occupations, the median income was $9,000 for a white male, $6,200 for a while female, $7,900 for a black male, and $6,300 for a black female.

In the rural South, which has become so dependent on manufacturing for its livelihood, a future economy based on technology and on service businesses could portend economic disaster. Although jobs in nonmetropolitan counties did grow by 11 percent between 1977 and 1983, that growth was largely in rural counties along interstate highways and adjacent to growing cities, and in rural counties that attract tourists, retirees, or students. For example, Southern rural counties with high rates of in-migration of elders grew two and a half times as much as the overall growth of rural counties.

Retirement counties with the highest rate of job growth, however, were concentrated in the eastern seaboard states from Virginia to Florida, and in Arkansas and Texas. The fastest-growing counties that are remote from cities and interstate systems (over 40 percent growth), for example, include coastal resort counties — Bay and Citrus in Florida, Carteret and Dare in North Carolina, and Horry in South Carolina (Myrtle Beach) — and mountain resort counties, such as Avery and Macon in North Carolina, McCreary in Kentucky, and Bath in Virginia.

Rural counties without beaches, spectacular vistas, or strong universities have little to offer high-growth industries and have a hard time competing with the likes of Research Triangle Park, Austin, Atlanta, or Nashville and their surrounding counties. One out of every three rural counties that is not next to a city and is not bisected by an interstate highway had fewer people working in 1983 than in 1977.

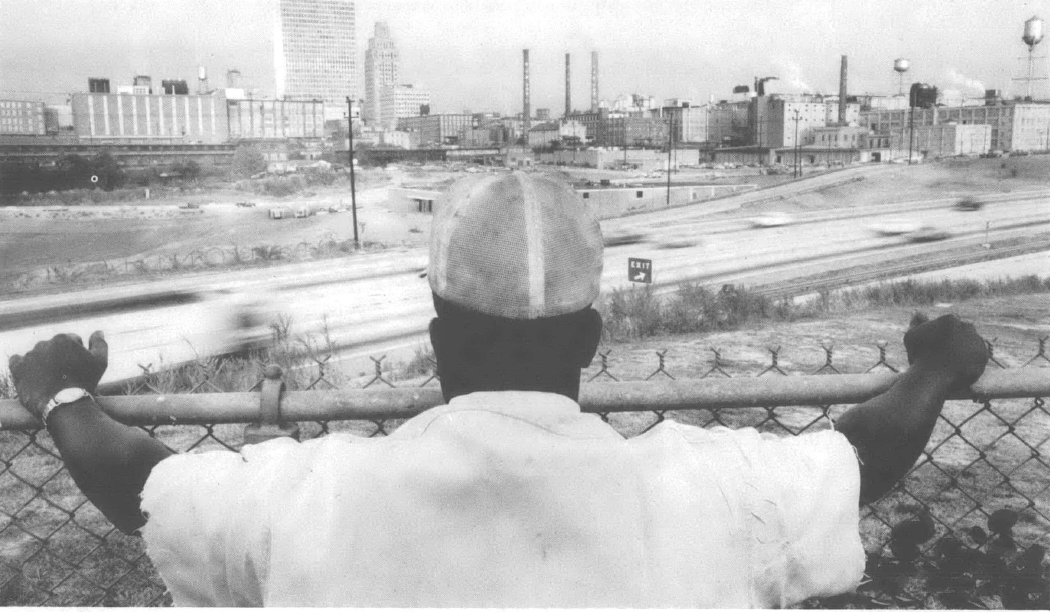

Still on the Outside Looking In

For all the problems facing rural counties, the most dire economic patterns are in counties with high proportions of blacks. Changes in employment between 1977 and 1983 in the South in fact are inversely proportional to the percentages of black residents. Those counties with fewer than 20 percent black population grew by 24 percent; those with 40-50 percent black population grew only seven percent; counties that are more than half black actually lost an average of 12 percent in employment. And many were already economically depressed.

Skeptics of racial composition of a county as a constraint on growth could point to the fact that counties with high percentages of blacks also have lower levels of average income and educational attainment, and could argue that those factors are the real culprits, not race. But even among just very poor counties in the South — those with no more than half the national per capita income — counties with a population less than one-third black had twice the rate of job growth of counties that are more than one-third black. And among only those Southern counties where no more than 40 percent of the adults had finished high school — far below the national average — those counties less than one-third black grew more than 50 percent faster than those more than one-third black — which indicates racism is a possible explanation and suggests growing economic disparities between races.

Work and Work Environments

As businesses that comprise the South's economy change, the work that people do inevitably changes. New technologies and new management styles (influenced strongly by growing foreign ownership) affect what a person does on the job and what a person needs to know and be able to do to advance economically. Qualifications for the emerging occupations are principally work experience and academic records. Rural workers have been much less likely than urban workers to be employed as managers, professionals, technicians, sales people, or clerical workers, and even smaller percentages of rural blacks held those jobs Southern rural workers have the lowest levels of educational attainment and achievement and the highest levels of functional illiteracy. This means that rural workers, and particularly black rural workers, are less likely to have the credentials to compete for the jobs that represent the greatest opportunities, which may turn out to be the biggest obstacle to rural growth in the South.

As technology is diffused into the workplace, it also is going to affect both how work is conducted and how it is managed. The question that no one seems able to answer yet is whether technology will increase the skills and knowledge required of workers and raise their wages, or will it decrease the skills needed and further degrade work. This question has not been answered because "it depends." It depends on whether workers, unions, and employers are willing to seize the opportunity afforded by technology to restructure work more democratically.

If employers utilize the experience and competencies of more highly educated workers by giving them more discretion and authority on the job, work can be upgraded and made more interesting. General Electric is preparing to open a new automated jet engine component plant in Wilmington, North Carolina using "supervisorless" production teams. "The traditional worker/first-line supervisor structure," according to the company's plans, "will be abandoned." As a result, "workers will be expected to exercise more independent judgment and creativity in addressing production problems."

If, on the other hand, technology is used to further divide labor tasks and more carefully monitor work, it will make work more tedious and exacerbate a dual economy. In a recent report from the Office of Technology Assessment for the Congress, a machinist commenting on the use of computer-controlled equipment said, "You get to be, in my opinion, a little weak-minded. . . . You can take a Chimpanzee, the light goes on, push a button. . ."

One factor that might accelerate more progressive management is the changing pattern of business ownership. An increasing number of firms are being acquired and started by foreign corporations and an increasing number are being bought out by employees. A large number of employee-owned businesses and foreign companies are trying unconventional and more democratic organizational models that alter the relationship between workers and management. Foreign companies are taking over all sorts of manufacturing businesses, most aggressively in the chemical and allied products industries and in the electrical and electronic equipment industries. Ironically, even as many American firms are fleeing to other countries to take advantage of lower labor costs, foreign businesses are expanding their U.S. manufacturing bases.

Readjusting the Sun Belt

All in all, there still is a Sun Belt, but it alone is failing to hold up the britches of the entire region. Overall growth patterns in the South hide residual — and in some places new — underdevelopment and poverty. The media attention to the growth centers has made policymakers somewhat complacent about the region's future. Only recently, as the Northeast recovered from the recession much more quickly and completely than the South, have they taken notice.

The structure of the region's employment is being reshaped once again, this time from manufacturing to services and information. The solutions most often prescribed for declining local economies are diversification and entrepreneurship. But knowing what has to be done and doing it are two different things. It takes time and requires more resources — both human and capital — than many Southern communities have at their disposal.

Twenty years ago there were federal agencies, such as the Economic Development Administration, the Small Business Administration, and the Appalachian Regional Development Commission, to help provide the support needed for industrialization. This time around the federal government is fading out of the picture, competing pressures for state revenues are building, and plant closings and falling farmland values are decimating local tax bases. More important, it is not clear that enough officials and policymakers fully understand the differences between 1968 and 1986. Too many development officials are still living in the past, protecting company towns by rejecting new jobs that threaten to raise local wages. As recently as 1984, local officials in South Carolina resisted a new Mazda plant because its wages were too high! And there are still towns looking for industrial revenue bonds to build industrial parks because they believe that is what will bring jobs and income.

There will continue to be growth in the sunspots of the South, and a small number of big "winners" in rural areas — but mostly in choice locations, easily accessible to airports, good schools, and quality restaurants and shops. The rest of the region will have to rely on its own resources, people, and wits to carve out a niche in the new economy. The long-term solution for many parts of the South obviously lies with education. That education, however, ought not be limited to the schooling of the children and young adults of the region, but ought to be offered to older adults who attended (or dropped out of) the many inferior schools in the South and to all adults who want new skills in order to be more effective participants in the economy and in planning the economy.

Tags

Stuart Rosenfeld

Stuart Rosenfeld is director of research and programs of the Southern Growth Policies Board and principal author of After the Factories: Changing Employment Patterns in the Rural South. (1986)