This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

One black woman is having trouble naming her business; another walks past 10 other black women to get a black man's opinion; musing aloud, another says women just don't have the stamina to stand up under the pressure of business; another wants to get ahead but continues to hire staff who don't perform. These women are linked by two invisible yet powerful threads. Each woman is committed to the social and economic development of black Americans, including themselves. And each faces powerful barriers that block her success.

External barriers from a male-dominated power structure conspire to keep black women in subservient and secondary positions in our society. Currently women earn 64 cents for every dollar a man earns. On the economic and social totem pole, the black woman's "place" is below that of the white man, the white woman, and the black man. Latest statistics show the median income of white men to be $15,401; $6,421 for the white woman; $8,967 for the black man and $5,543 for the black woman.

In addition to being detrimental materially, external oppression in the form of social disapproval, low expectations, and little encouragement has damaged black women emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually. After having her leadership doubted for hundreds of years, is it a wonder that the black woman harbors doubts about herself? In effect, black women see themselves through the eyes of whites and black men: inferior, powerless, less smart, and less capable, especially in business.

We have internalized these negative messages. They have become negative "scripts" guiding our self-defeating actions as blacks and as women. They have become internal barriers, complementing the external barriers that created them. The external barriers are real, and we do not make light of them; however, the Black Women's Leadership and Economic Development (BWLED) Project believes that internal barriers, the ones in our own heads, are the real killers.

The goal of the project is to identify and break down internal and external barriers that stop black women from operating successful economic development ventures and taking responsibility for our own welfare and that of the black community. The project provides an avenue for black women to love and support each other and, at the same time, challenge each other to dream, to envision what we want, and then to get it.

The following example illustrates the great need for the BWLED Project. A black woman in south Alabama created a catering business. Happy and excited, she got her business off to a good start. The community received her and her product well. With the market tested and the prognosis good, she soon had more callers than she could handle alone. She asked her husband, who had not been supportive of the venture, to keep her business books. He said he would, but he didn't appear to have any real energy or interest. Her business seemed like heaven, an avenue out of her dead-end agency job to independence — but within a matter of days it slowed to a trickle. She began to feel torn between her responsibilities as a wife, mother, and new entrepreneur. Her initiative to find business declined. When asked about it, she only says, "My family was not very supportive and I was being pulled in too many different directions." Today the business amounts to another unfulfilled dream.

Although she had more than adequate start-up money and community support, this woman had a hard time continuing successfully without her husband's support. She did not have a vision of herself succeeding and was surprised when people responded so positively. She had problems seeing herself as a good mother and businesswoman at the same time.

The above woman is "scripted" both racially and sexually to feel inferior, powerless, not quite good enough, unable to "know" her own personal power. She would find support and identification for her struggle from other women in the BWLED Project. And she would be given feedback as she attempted to understand how internal barriers robbed her of her dreams, energy, and initiative.

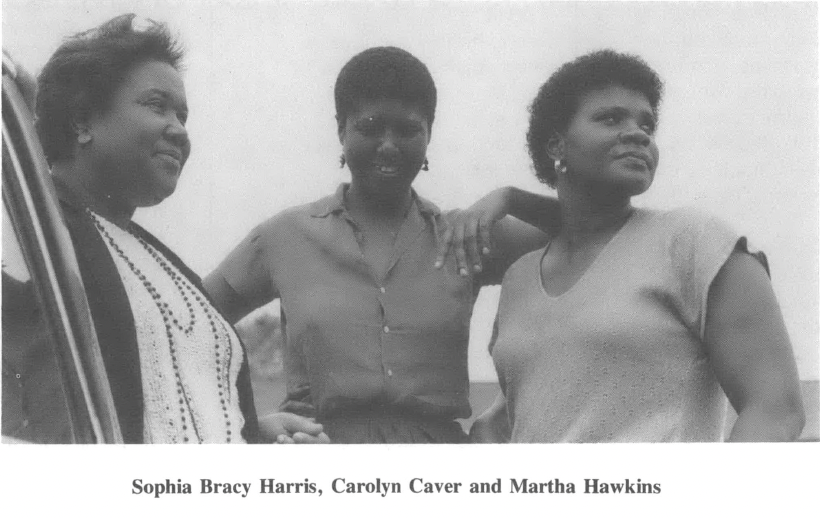

According to Sophia Bracy Harris, the executive director of FOCAL (Federation of Child Care Centers of Alabama), "Women all over the country affirm that internal barriers are real and they find the objectives of the project exciting." Based in Montgomery, FOCAL provides technical assistance, training, and advocacy for a network of about 90 child-care centers; it is particularly active in training low-income black women to take leadership roles in their communities. Sophia got the initial BWLED Project off the ground in April 1984, after she attended a workshop sponsored by the National Black Women's Health Network.

In working to break down the feelings of inferiority and to help women see themselves as peers with others and each other, the project adopted FOCAL's guiding set of concepts and principles:

• Vision: seeing and defining what we want;

• Responsibility: taking leadership and responsibility for our own lives and the realization of our human potential;

• Proactive thinking, behavior, and planning: getting away from the powerless position of reacting, petitioning, rebelling, and protesting in order to get the powerful to fix things, provide for us, accept us;

• Risking: choosing to experience fuller measures of our true reality;

• Moral and ethical behavior: choosing a morality that is consistent with our vision and dreams of a world overflowing with unity, justice, love, and progress.

The project's main energy centers on having women declare a vision (what it is they want). Often women can readily name the external barriers holding them back, but when we are asked to say what our visions for ourselves and the world are, most of us struggle. Black women are so accustomed to thinking about why we can't succeed that when it comes to saying what it is we want (if no barriers exist), nothing comes. Black women stop dreaming. This project will see black women dream again.

Through sharing their concerns, fears, feelings of inadequacy, visions — their "pieces" — project participants deal with some of the most common conflicts faced by black women who aspire to economic success and independence: being seen as insensitive to the historical oppression and struggle of black people, as someone who leaves behind the black man and her family, and as an aggressive manipulator who can no longer be a loving, nurturing caretaker.

My Turn: Closer to Home

Our city spent $100,000 to tell us what we already knew — what was wrong with our neighborhoods. They assigned people who didn't know any more than we did, so we asked for $200,000 to use for our own people. We said: "We're here because we don't know, so why do we need you if you don't know?" Then we got skills training for neighborhood leaders, and now people are thinking of putting up grocery stores and housing co-ops instead of vest-pocket parks.

If we fail, so what? Nobody else has been able to do anything for our neighborhoods. All those expert people were there saying what was needed for us, and none of their programs worked. I say let the people do it; let us show what we can do. And if we fail in our neighborhood, it will be no worse than what other people have failed to do for our neighborhoods.

— Sarah Price, Alabama

The project allows a woman to resolve her vision of her leadership with the love of her family and others by throwing off all contaminated feelings of resentment, shame, doubt, hatred, and fear of herself and others. Feeling okay about herself, she feels good about others. We also need to realize our vision within the context of our own values and wholistic vision as black women. We may decide, for example, that crying is a healthy way to deal with intense emotions in our businesses. Eventually, a congruent picture of a loving, nurturing, in-charge black woman will emerge.

In shaping their visions, project participants are encouraged to risk creating something that may look different from the traditional. Sophia Harris says, "Let's create our own definition of economic development." Her dream is to see us get away from the let's-go-out-and-get-rich-fast scheme to something that has more of a community ownership to it.

One core project member, Martha Hawkins of Montgomery, recently shaped and launched a vision: Martha's Home Cooking, a catering service. Martha says the BWLED Project had everything to do with her getting the nerve to try catering. She explains, "The experience motivated me to take a look at my life. The other women had been educated, and I felt inadequate with them. Finding strength and support from the group, I went back to school and got my GED, started taking courses in sociology at Troy State University, and tried my hand at catering three days a week."

Martha says she was terrified at first; she was concerned about what people would say if her business failed. She eventually said, "I'm gonna give it all I got, full-time." Today, five months later, she is amazed that she is paying four other people to work for her. Martha's Home Cooking primarily caters lunches for industrial sites. With business booming, she says, "I am now scared and excited all at the same time, and it feels wonderful." Martha is currently looking for a building that will take on the name Martha's Place, a homey, warm, loving restaurant. Her vision is quite clear and at this point, the question is not will she have a restaurant but how soon.

Many of the women in the project look at internal barriers that block economic success; they start where they hurt the most. One core member, Debra Walker, decided that she didn't need to stay in an unhealthy relationship. Redefining "security," she decided that she was of value outside of anybody and anything. Debra then accepted the fact that she was ultimately responsible for herself. "It didn't make any difference what anyone thought or felt because if I didn't intuitively feel okay, then it wouldn't be okay for me," she says. This trust in her own sense of what is good comes when a woman decides that she is valuable and so is what she feels, thinks, intuits.

Starting where they hurt the most, with energy and commitment to personal growth, women experience "spill-over" everywhere. It is hard for women to grow, feeling themselves as peers in personal relationships, and then continue to feel inferior on a job or vice-versa. After leaving her unhealthy relationship, Debra left a secure job at Miles College, joined with two associates, and formed Human Resource Services, Inc., as principal training consultant.

The BWLED Project has not only brought us happiness, joy, and excitement. All of us have also experienced pain and fear at different points. For example, having launched her business, Debra says she still fears not making enough money to support herself and her child, is scared that folks will not accept the services of her business since it is black, and is not able yet to deal with her relatives' and friends' fears that her business will fail. Other participants say their growth has been difficult at times but their levels of gain have been in direct correlation to the levels of risk.

The project is no panacea, however. There is no need for any woman ever to think she has it all, that she is no longer racially and/or sexually scripted, that she has mastered the guiding concepts and principles. In writing this article, I was having trouble focusing on what I wanted to say. A colleague asked: "What is your vision?" I asked, "Vision?" He said, "Yes, you were going to develop an outline, right?" I laughed at myself loudly: "Vision . . . I was thinking outline like in English Composition 101." I had not decided what I wanted in this article, what I wanted it to do, how I wanted people to feel when they read it. The encounter was sad, enlightening, and funny at the same time, because I understood how important vision is to anything and anybody, yet I had missed it.

These jewels of revelation happen all the time in the project, and they will continue to happen as we black women — sometimes in pain, oftentimes in fear, other times with excitement — visualize our lives, our families, our communities, and the world as we want them and then chart our courses, knowing we will get what we envision.

Tags

Carolyn Caver

Carolyn Caver became the coordinator of the Black Women's Leadership and Economic Development Project in October 1986, and wrote this article as an orientation to her new responsibilities. (1986)