This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

For the past 10 years, the $650-million-a-year catfish business has been Mississippi's fastest growing industry — highly praised as a positive example of economic development in a state which still ranks last in most economic categories. Seventy-five thousand acres in the state are devoted to intensive commercial production of farm-raised catfish, and more acres are being bulldozed every day. And unlike most of Mississippi's traditional farm products, the catfish are processed as well as raised right here in the state, in processing plants mostly owned by the farmers themselves — thus providing needed jobs and revenue for ailing local economies.

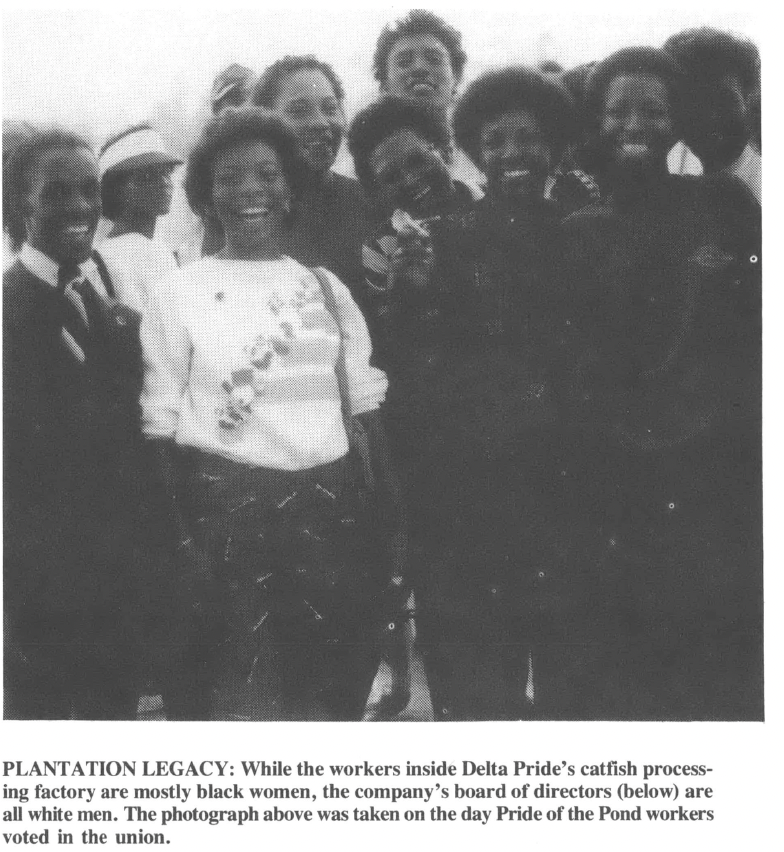

Yet this widely touted "salvation" for Mississippi's farmers has a grim underside for the mostly poor, black, and female workers in the processing plants. Although the state's high unemployment rate (13 percent officially) means that they need the jobs, many blacks in the area see the relationship between the catfish farmers and the processing workers as in some ways a continuation of the centuries-old exploitation of rural blacks by wealthy white planters. This conflict of interests erupted recently in a hotly disputed union election at the state's largest catfish processing plant — the Delta Pride plant in Indianola.

Delta Pride is the largest catfish processing plant in the world. It is owned by the white Mississippi farmers who supply it. About 90 percent of the commercial catfish consumed in this country comes from Mississippi, and half of that is processed by the 1,100 workers at Delta Pride.

Workers' Pride

On October 10, 1986, the Delta Pride employees — almost all black women — voted by a margin of 489 to 346 to join Local 1529 of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) union. This election was the culmination of a long and difficult UFCW campaign throughout the region, and represents one of the most significant victories in the state's labor history.

Labor organizing has always been difficult and dangerous in Mississippi. Particularly in the Delta, where land and resources are mostly owned by a few wealthy whites and where jobs of any sort are scarce, union efforts meet with stiff opposition from the powers that be.

But working conditions inside the catfish processing plants have given employees there the impetus to demand more control over their situation. Dorothy Kembrough, a leader of the organizing drive at Delta Pride, says the union won because workers were "being treated like dogs. . . . There comes a time when you can't take it no more."

Mississippi's catfish industry boasts that it employs over 4,000 people with a payroll of over $40 million. Yet on a recent paycheck, Dorothy Kembrough grossed $199 for 47 hours of work. After taxes, insurance, and $2.50 for "uniform dues" — deducted "whether you use the uniforms or not" — her take-home pay was $150.

She received the same $3.85 per hour for regular and overtime hours. The average worker in Mississippi's food products manufacturing industry receives $5.35 per hour, and the national average for the sector is $8.17 an hour.

The phrase "regular hours" is misleading. Delta Pride workers say they never know when they will start work or get off. Required to report to work at eight in the morning, they often have to wait several hours without pay until fish are brought in. They also are required to work on Labor Day and the Fourth of July.

Respect for the workers' privacy and dignity — as well as regard for their safety — has been minimal. Workers must ask permission to go to the bathroom, and male supervisors have been known to follow them in. Until recently the bathrooms had no doors. Several workers say that some white supervisors had to be moved because they "have gone to bed with some of these black women," who allegedly complied in order "to get more money."

Mary Young's job at Delta Pride is skinning the fish on a machine. Her description of plant conditions is graphic: "I'm right next to the line where they take the heads off, take the guts out, and then I skin them. Guts and blood are flying everywhere."

She says that many workers suffer from skin rashes and swollen eyes. "You have to pay for the safety glasses," she adds. "Most people don't wear them." In addition, she says, the floor is generally covered with water, and the smell "is enough to turn your stomach."

Accidents are also frequent, Young reports, especially in the filet department. Despite the safety gloves, she says, someone gets cut every day. The main reason is pressure on each worker to filet 800 pounds a day. Before the union drive started, moreover, there was no nurse on duty at the plant. Young contends that several people have lost fingers that could have been saved if they had not had to wait around for someone to take them to the hospital.

Pro-Union Votes

While the union cannot solve all of these problems right away, it does give the workers a channel for voicing their grievances which the company is bound to respect, at least to some degree. But workers at the several catfish processing plants in the Delta where the UFCW held organizing drives had to stand up to various kinds of opposition in order to claim their right to union representation. In some cases, the plant owners have decided to close the plants rather than abide by the election results.

On September 26, 1986, employees of the Pride of the Pond processing plant in Tunica voted 60 to 10 in favor of the union. Since then, however, production at the plant has been halted while stockholders "mull over" whether or not to reopen it. Workers heard threats before the election that the plant might be closed if the union won. But employee Patricia Scott says they felt they "had no other choice, the working conditions were so bad." Scott's starting pay was $3.40 an hour, with no benefits and no holidays off.

Elsewhere in the region, workers at the Farm Fresh plant in Hollandale voted for the union over a year ago, but have yet to get a contract. Another plant in Belzoni was organized back in 1980, but it closed in early 1986, throwing 150 employees out of work. And the union lost an election at the Con Agra plant in Isola this past summer, but UFCW spokesperson Bobby Moses said the union planned to file an objection with the National Labor Relations Board, charging the company with intimidation and with "violating the rights of the people to a free election."

Intimidation was also rampant during the Delta Pride campaign, according to workers there. Immediately after workers began passing out cards to authorize an election, Young said, "People started getting fired." The union drive started January 25; the first worker was fired January 28.

"They harassed us a whole lot. Foremen would come up and punch you in your back. They would do a little quick jab on you and say, 'You know you're on your way out the door, don't you?' They told me if I didn't like it I could leave any time I felt like it. The supervisors and the plant manager would outright tell you 'You can go back to the cotton field if you don't want to do what I say,'" Young added.

Share the Power

Delta Pride also flooded its employees with a barrage of propaganda depicting UFCW organizers as "outsiders" coming in to exploit the workers. A strike by meat packers at a Hormel plant in Minnesota was cited as an illustration of the union's power "to strike workers out" of a job. Also common were threats that Delta Pride would close after a union victory; and at a company-sponsored "party" the night before the election, workers were urged to follow this slogan: "Let's Keep the Party Going, Vote No!"

White business leaders spoke out against the union. The local paper, the Enterprise-Tocsin, editorialized: "The company owners and managers at Delta Catfish are sincere about their future plans to keep raising salaries and benefits of employees as the fast-growing catfish industry continues to prosper. This plant is only six years old, and whatever past inadequacies were caused by exploding growth are now being addressed and things look bright for whoever is lucky to have a job out there."

Workers also report that the company invited Fayette mayor Charles Evers — brother of slain civil-rights leader Medgar Evers — to tour the plant before the vote, and that Evers tried to convince the employees that they didn't need a union.

Support for the catfish workers was strong in Indianola's black community, however. One important factor was the successful school boycott held in the town earlier in 1986, when blacks forced the hiring of a black superintendent for the predominantly black school system.

Most of the catfish workers had supported the boycott. In turn, the community supported their struggle, despite the defection of Willie Spurlock, a key leader of the boycott. Workers attended rallies at churches and at the plant, and received encouragement from local merchants when they went shopping.

In addition, local members of the United Steel Workers talked with catfish workers about how union representation had improved their situation. The NAACP also lent active support.

The Rev. Michael Freeman, pastor of the Raspberry Chapel United Methodist Church and a strong supporter of the union effort, says, "The community really supported the employees because now they see not only the professionals are united (referring to the school boycott) but also the labor base. . . . We have sent a message from the community that no matter what positions we have in life, we care for each other. I think this is significant."

These union elections are also sending a message that black people want a voice in determining the future of Mississippi's catfish industry — an industry whose future is by no means assured, despite the dazzling claims of its proponents. Last year catfish prices fell for the first time in a decade, from 73 cents to 63 cents a pound. At the same time, catfish consumption is growing at the lowest rate in 10 years. The threat of overproduction — leading to devastation for many newcomers to catfish farming — has prompted the American Catfish Institute to launch a multimillion-dollar advertising campaign on the West Coast and in the Northeast, where currently only two percent of all catfish is consumed. And Mississippi State University has begun a $2 million food science program aimed at finding new ways to prepare and market catfish.

The Delta Pride union election means more attention should also focus on improving working conditions inside the industry's plants. In the past, the catfish industry has meant opportunity for some, exploitation for others. Now, it is hoped, both sides will have to discuss common interests and goals.

"Never," says Rev. Freeman, "have blacks been able to come to whites here and say, 'Let me tell you what's good for me, and then let's sit down and talk and see what's good for each other.' The thing is, let's share the power and economics in the community. For too long, they have had it all."

Tags

Michael Alexander

Mike Alexander is a freelance journalist and reporter for the Jackson Advocate. (1986)