The Politics of Economic Development

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

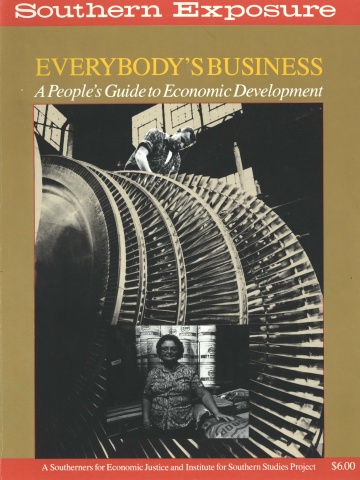

Birmingham's empty steel mills dramatically draw a picture being repeated, on a variety of scales, across the South. The economy which binds our communities together is drastically changing. As Stuart Rosenfeld reveals (page 10), current trends point to deepening divisions between two Souths: the Sunbelt's mostly urban bright spots — few and far between — and a fading countryside. Within the cities, two Souths are also solidifying: one for the information-age elite and another for the predominantly black and female cast-offs who are lucky to find even low-paying jobs.

Jolted by these stark contrasts, many people who have left economics to the experts are now looking for ways to save their communities. Southerners for Economic Justice and the Institute for Southern Studies undertook this "people's guide" in order to identify how ordinary Southerners can influence economic development. What Greater Birmingham Ministries and Neighborhood Services Inc. have been doing in Birmingham (page 96) demonstrates that local citizens can create effective alternatives to the death sentence being handed down for their communities.

All across the region, Southerners are already engaged in creative approaches to economic revival. In this book, you will find projects that involve innovative education (page 56), grassroots leadership development (page 62), worker organizing (page 76), political action (page 83), corporate accountability (page 79), and affirmative action (page 48), as well as models for worker-owned businesses (page 52), alternative enterprises (page 86), sectoral intervention (page 71), and community-oriented state policies (page 65).

These stories emphasize the need to expand local alternatives and to confront state development policies which, as James Cobb and the Southern Labor Institute show, keep the region depressed by undervaluing its people. The local focus highlights the fact that all economic power is built on the productive talent of local people. Ironically, while corporations must trace their success back to specific localities, they will always allow neighborhoods, communities, and even regions to be written off in the name of more profitable opportunities elsewhere.

The profit motive which drives business can not adequately factor in the value of family, community, love of the land, rootedness, culture, or hope. The emphasis on alternative approaches means we urgently need a "new bottom line" in discussions about the economy — one that measures success in terms of people and human values rather than dollars and return on investments. Even locally controlled enterprises can miserably fail the people working in them unless they are infused with genuine democracy; see the examples from Michael Alexander and Martin Eakes (pages 32 and 107).

The success stories are mostly small and tentative, but these models of alternative economic development must be welcomed into the mainstream and supported by state policy. State governments set the stage, for better or worse, for economic development. Typically they manipulate public resources in response to an agenda set by large corporations.

Take the state of Tennessee, for example. It recently granted $20 million for "employee training" to General Motors, without any control of who or what the training involved (page 45); but the state denied funds for the Mountain Women's Network to begin a community-based college geared to local development needs (page 60). As Carter Garber explains (page 115), citizen research and action targeting the contradictions in Tennessee's industrial recruitment policies have become a model for others around the region. Southern communities and grassroots coalitions must now band together and exert their influence over state-sponsored economic planning and development.

This guide comes at a historic moment. Rather abruptly, we no longer hear talk about the impersonal, distant "engines of progress" that will bring prosperity for all. Instead, we are witnessing an economy that has ceased to offer hope to millions of people in the richest nation on earth. Horrified at the ugly face of capitalism, people who once avoided political debate about our economy are now probing its inner workings and calling its decision makers to account for their actions.

Churches in particular are publicly raising questions about economic behavior that only radicals asked a few years ago. The widespread concern within churches, and their crucial importance in transforming economic policy, has led us to include a section on church-initiated strategies.

A detailed analysis of the South's economy would reveal its intimate and intricate ties to a global economy. Our focus is much narrower. But any guide to alternative development strategies must acknowledge that the region's economic decline and especially the widespread layoffs in steel, textiles, furniture, and other basic industries are being blamed on citizens of the third world who allegedly are "stealing our jobs."

Political, business, and labor leaders have jumped on the protectionist bandwagon. Yet the debate over restricting imports never gets to the central issue of who controls and who benefits from the flight of capital. As a Creole organizer succinctly put it, "Working people around the world are fighting over the crumbs while the international corporations are making off with the entire loaf of bread."

Rather than reacting to the symptoms of a system that will continue to put profits before people, this book presents a challenge to organize new programs, model enterprises, and political activities that enlarge the areas where we exercise democratic control of the economy. There will be disagreements and plenty of tension along the way. People are under a level of stress that hasn't been seen in this country since the Great Depression; but stress can be energizing, especially when it is shared. Perhaps people not on the bottom could use a little more stress. Instead of writing off the testimony of suffering people as "hand wringing," all of us should use their experiences as the gauge by which we judge the quality of our society.

For substantive change to occur, other challenges must be met. State government, regardless of what it says, will continue to ignore development strategies accountable to local communities — unless they are forced to by local political organizing. And in many areas, the challenge is for even more basic organizing, or what the experts call "capacity building" — bringing together the unorganized to share information, develop leadership skills, make decisions, and begin to wield influence over the economic decisions affecting their lives.

For progressives who seem to show up at each other's conferences on The Economy in Crisis, the challenge is to welcome new members to your ranks. The character of the economic development debate is decidedly white male. If that doesn't change, if women and people of color are not sought out as partners in economic brainstorming and planning, then good intentions will remain just that.

Unions, under so much pressure in the South, must break out of their paralysis and involve new leaders in bolder strategies. Women — particularly women of color — are the future of the labor movement. They fill the ranks of the unorganized, low-wage industrial and service jobs that form one pillar of the post-New South economy. Given the will, unions are in a position to help working women organize into a political force that would have far-reaching consequences for our struggle for economic justice.

Make no mistake about it: economics and politics are closely linked. Both are nothing more than organized decision-making. What would state policy, what would local and regional economics look like if the masses of people, not corporations, were making the decisions?

Tags

John Bookser-Feister

John Bookser-Feister and Leah Wise are staff members of Southerners for Economic Justice, which coordinated this special edition of Southern Exposure with the Institute for Southern Studies. (1986)

Leah Wise

Leah Wise, Research Associate at the Institute for Southern Studies in Atlanta, traveled in China in December 1973-January 1974. An oral historian, she has been in the South gathering records and recollections of our peoples struggles for the past seven years. (1975)