This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

Development in the South can best be defined as the process by which the region's residents make the economy better serve their fundamental needs. These include:

• the right to meaningful work that is not life-threatening in either the short or long term. This right implies both a safe workplace and a safe environment.

• the right to economic security, both in terms of job security and equitable remuneration for work done. This remuneration should be sufficient to insure decent housing, health care, etc.

• the right to participate as fully as possible in any decision-making affecting their livelihoods, i.e., democratic control of the workplace.

• the right to preservation of cultural integrity. Economic development should not destroy the cultural integrity of the people for whom development is taking place.

This definition has several important implications. First, it emphasizes that development is a process rather than a plateau of achievement measured simply in dollars and cents. Each project should be measured in part by how well it contributes to the overall development process, by how well it satisfies these basic rights.

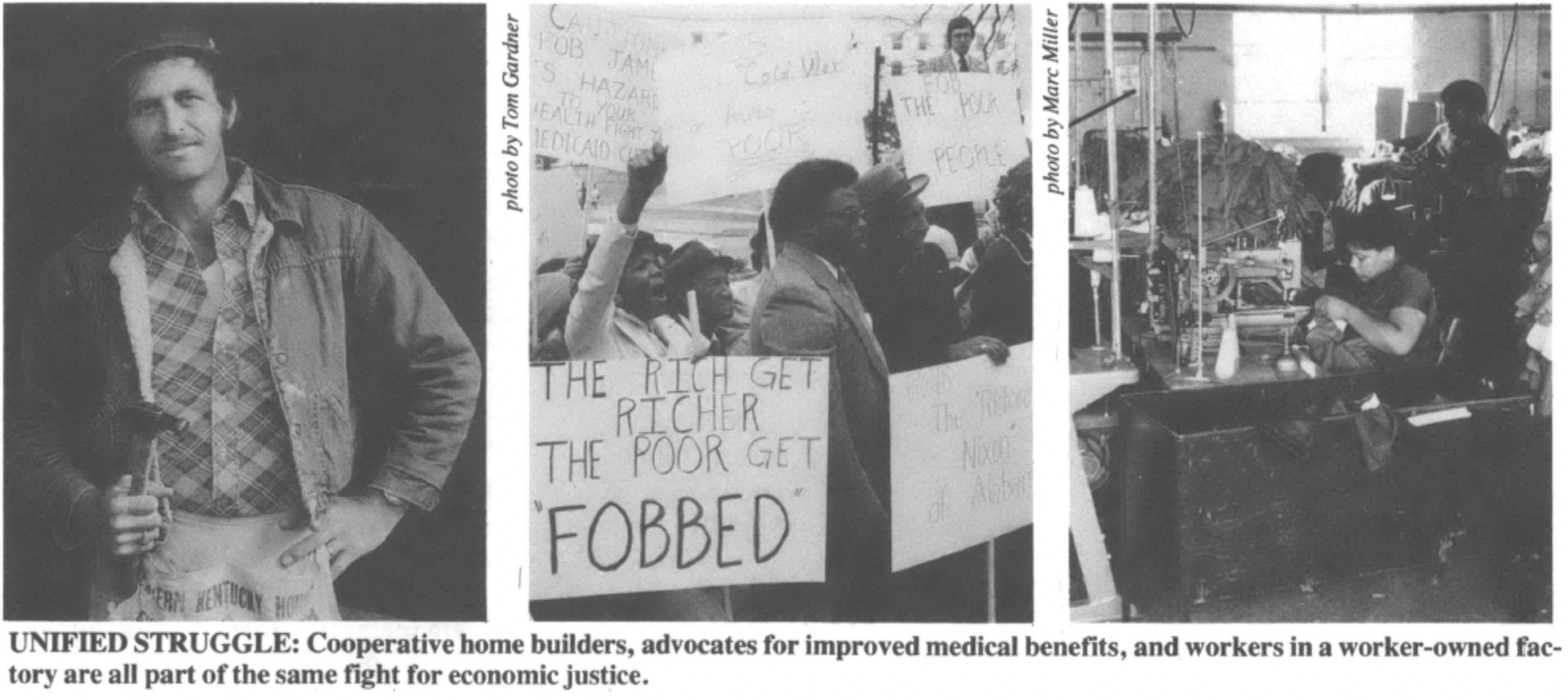

Second, this definition breaks down the dichotomy between economic development organizations and advocacy or issue-oriented groups with a basically political approach to problems. In reality, most citizen groups in the South are engaged in activities somehow related to economic development, whether they are battling strip mining in East Tennessee or providing construction jobs for low-income women in Mississippi.

Traditionally, groups involved in grassroots economic development have been categorized as either (1) improving the financial well-being of low-income people through fostering economic independence and self-reliance (such as through credit unions, cooperatives or worker-owned businesses); or (2) directly challenging existing corporate or government policies. Groups in this latter category have fought utility rate hikes, occupational diseases, racial and sexual discrimination in the workplace, land ownership concentration, environmental abuse, tax inequities and inadequate housing for low-income people. They have often been dubbed "political" rather "economic," but such a distinction misses the larger meaning of economic development and exacerbates the weaknesses of current organizing.

If, on the one hand, cooperatives and other alternative enterprises restrict themselves to economic aims, they may end up being co-opted and buying into the larger political economy and ultimately their own oppression. If, on the other hand, advocacy organizations limit themselves to political opposition, they may end up always on the defensive, unable to offer creative alternatives that effectively respond to people's immediate needs.

Economic development strategies in the future must find ways to eliminate the tensions between groups doing advocacy work and those engaged in trying to create locally owned and controlled businesses. Only comprehensive strategies that integrate both political and economic approaches can adequately address people's needs.

Tags

Steve Fisher

Steve Fisher teaches political science at Emory and Henry College. These thoughts are a synthesis of ideas presented at a May, 1982 workshop funded by the Mott Foundation at the Highlander Center. It draws heavily on background papers prepared for the meeting by Sally Maggard and Bill Horton. (1986)