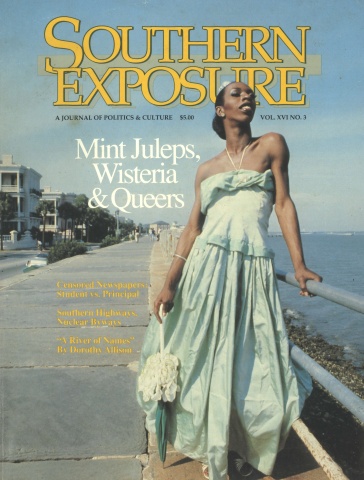

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

Milo Guthrie was only 10 years old when his great-aunt Ethel Pilcher died, but he remembers her well. Hers was an old and respected Virginia family, and great-aunt Ethel herself had been principal of the A.P. Hill School in Petersburg in the 1920s. That was why the story about the little girl never made any sense.

Family legend had it that great-aunt Ethel and a friend of hers, a social worker, had adopted a girl who died of scarlet fever a few years later. When Ethel asked to bury the child in the family cemetery plot, the family refused.

“A big controversy erupted,” Milo recalled. “They made a whole big deal in those days about the family burial ground. This girl wasn’t part of the family, so I just figured that was the reason they didn’t want her buried there.”

Then, a few months ago, Milo was talking with his father. The subject of his great-aunt came up in conversation, and Milo learned the truth behind the family legend.

The social worker, it turns out, was a woman. Great-aunt Ethel, it turns out, was a lesbian.

“It was news to me, but it made perfect sense,” Milo said. “I had come out to my father, so I guess he thought I might be interested to know about my great-aunt. It just confirmed what I knew all along — that gays and lesbians are everywhere.”

Such stories are not uncommon among Southern families. We often hear tales of an “odd” uncle who never married, a spinster aunt who lived with a “friend,” a great-grandmother who liked to drink and smoke and hunt and chew tobacco. The loves and passions of these forebears always go unmentioned, unnamed. They were part of the family, we are told, but the silence says something different, says they were somehow never fully understood, never fully accepted, never, like the adopted daughter of a lesbian aunt, fully family.

In the process, the silence also obscures the daily lives of Southern gays and lesbians, conspires to place their experiences beyond the reach of memory. The result is a hidden history of Southern homosexuals — a history that crosses all boundaries of age, gender, race, religion, politics, and economic class to include all Southerners who have dared to love members of their own sex.

As author Jonathan Katz demonstrates in his Gay American History, Southern men and women have dared to love freely since before Europeans invaded the continent. Indeed, records of the earliest white explorers clearly indicate that cross-dressing and homosexual marriages were commonplace among native Americans.

“During the time that I was thus among these people I saw a devilish thing,” the Spanish explorer Alvar Nunez Cabez de Vaca wrote of his captivity among the Indians of Florida from 1528 to 1536. “I saw one man married to another, and these are impotent, effeminate men and they go about dressed as women, and do women’s tasks, and shoot with a bow, and carry great burdens . . . and they are huskier than the other men, and taller. . . .”

In Georgia and Florida, lesbianism was frequent enough among native Americans in 1595 that the Spanish missionary Francisco de Pareja took note of it in detailing questions priests should ask their penitents. Under questions “For Married and Single Women” he included, “Woman with woman, have you acted as if you were a man?” Under questions “For Sodomites” he included, “Have you had intercourse with another man?”

The growing number of white settlers did not deter the original Southerners from the “devilish thing.” In 1721, Jesuit explorer Pierre Francois Xavier de Charlevoix wrote of Indians in the Louisiana area, “It must be confessed that effeminacy and lewdness were carried to the greatest excess in those parts; men were seen to wear the dress of women without a blush, and to debase themselves so as to perform those occupations which are most peculiar to the sex. . . . These effeminate persons never marry, and abandon themselves to the most infamous passions, for which cause they are held in the most sovereign contempt.”

Nor did native Americans confine their passions to their own people. In his 1830 autobiography, Kentucky settler John Tanner described an Indian man who was “one of those who make themselves women, and are called women by the Indians. . . . She often offered herself to me, but not being discouraged by one refusal, she repeated her disgusting advances until I was almost driven from the lodge.” Other Indians “only laughed at the embarrassment and shame which I evinced.” Eventually, the Indian “woman” gave up on Tanner and married an Indian man with two wives.

The “embarrassment and shame” of heterosexuals like Tanner quickly became the dominant force that shaped the daily lives of lesbians and gays. In 1778, Lieutenant Frederick Gotthold Enslin was court-martialed for attempting to have sex with a fellow soldier. General George Washington approved the sentence “with abhorrence and detestation of such Infamous Crimes” and ordered Enslin “to be drummed out of Camp tomorrow morning by all the Drummers and Fifers in the Army never to return.”

Loving members of one’s own sex was declared a crime in the new nation, and by 1880 the U.S. Census reported that 63 people were in federal prison for “crimes against nature.” Thirty-five were from the South, seven each from Mississippi and Tennessee. Thirty-two were black.

Just as blacks struggled to create their own culture in a climate of violence and lynch law, Southern gays and lesbians of all races shaped their own lives under the threat of life imprisonment, castration, and electric shock “therapy.” Almost always, this meant concealing themselves, their lovers, the most basic facts of their lives. Consider, for example, the case of George Greene, an upstanding citizen of Ettrick, Virginia. He worked hard, married a widow at age 40, and remained faithful for 35 years. On the day he died, a St. Louis medical journal reported in 1902, “the wife called in assistance to prepare the body, when deceased was discovered to be a woman.”

Even though “George” was a woman who had disguised herself as a man and married another woman, the medical journal referred to her, without irony, as “a well-known citizen of Ettrick.” Perhaps, history seems to suggest, heterosexuals don’t know their fellow citizens (or their own communities) as well as they think.

Taken together, such historical anecdotes reveal just how “hidden” lesbian and gay history has been — and just how much of heterosexual history has been a masquerade, a way of dressing up homosexuals to suit straight people. Like the good citizens of Ettrick, heterosexual society denies the very existence of lesbians and gays. Simply to say, “I am, we are” is to be exposed to fear, hatred, and violence.

Yet, as the stories in this cover section of Southern Exposure show, Southern lesbians and gays have done more than simply declare their existence. In the years since World War II, they have struggled to shape their own culture in the fullest sense of the word. They founded a gay newsletter on a South Carolina military base in the midst of war, staged campy theater in small-town drag bars, created rural sanctuaries in the Ozarks and the Blue Ridge, and kept alive a tradition of storytelling and bodacious humor.

They have also taken an active role in the civil rights movement, and in doing so have challenged the movement to expand. It has moved from the day when Martin Luther King Jr. banished civil rights activist Bayard Rustin from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in part because Rustin openly declared his homosexuality, to a day when Jesse Jackson could stand before the nation on prime-time TV and call for gay and lesbian rights.

Such a transition underscores how far the movement has come in 25 years — and how far it has to go. It is no longer enough to say “I am, we are.” As activist and author Mab Segrest points out in her article on page 48, the time has come to draw on the rich culture of the region to build a Southern freedom movement that recognizes gay leadership. Freedom for lesbians and gays means creating a Southern family that includes great-aunt Ethel, that welcomes all our relations into the fold, that acknowledges each of us for who we are. It means learning to talk freely about our bodies, our sex, our selves. It means freedom for everyone, gay and straight. It means, ultimately, granting ourselves an essential freedom — the freedom to love.

— The Editors