One Big Community

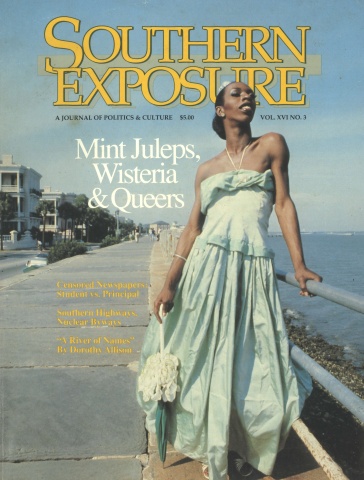

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 3, "Mint Juleps, Wisteria, and Queers." Find more from that issue here.

After World War II, gays and lesbians returning home created communities for themselves in big cities and small towns across the South. The closet door swung open for the first time, and homosexuals found they could come out in public without fear.

In Richmond, Virginia, gays and lesbians enjoyed a full social life. They ate at restaurants and danced at bars, they skated at roller rinks and partied at the Moose Lodge, they made love in movie houses and swam in public lakes.

“Life was much more open in those days than it is today,” one gay man recalled. “We had a lot more freedom. As long as we didn’t get out of hand, the authorities just turned their head.”

Mark Kerkorian (not his real name) was a teenager living at home with his parents in Richmond in 1944. For him and other young gays, downtown was a paradise from the Second World War until the early 1950s.

Mark described a scene long vanished of a downtown where, especially on weekend nights, cruising went on unchallenged in the men’s rooms and the men’s grills in the basements of most of the hotels, in the Greyhound bus station, and in most of the movie theaters along Broad Street.

The bars Mark remembered best were Marroni’s and Sepul’s. Marroni’s opened in 1946 or 1947 in the ground floor of the Capitol Hotel. Sepul’s opened in 1950 or 1951 diagonally across the street, where the parish house of St. Paul’s Church is now located. Both bars were small mom-and-pop operations.

Benny and Maria Sepulveda, who ran Sepul’s, “were very, very good to the gay community,” Mark recalled. “They liked us and they were very friendly with us.” Their establishment consisted of a restaurant (mostly straight) in the front and, through a little doorway, a back room with booths and a jukebox reserved for gays.

“Mrs. Benny,” as Maria was affectionately known, was especially protective of her gay clientele. “The only stipulation the Sepulvedas made was that if we sat in the front part then we had to behave ourselves,” Mark said. “No limp wrists flying in the air and no gay talk and no flitting around.”

In the back room, Mark recalled, dancing was permitted, “as long as we didn’t get too rambunctious.” On Halloween some men came in drag.

Marroni’s was more sedate; there was no dancing permitted there. Both places were dimly lit, typical of gay bars of the era.

Because of strict racial segregation, neither Sepul’s nor Marroni’s was open to blacks. Mark recalled that black gays “had their own private community, and there was no intermingling” between black and white gays.

After the bars closed, gays socialized and cruised at the Oriental Restaurant, located above a florist’s shop on the southeast comer of Fifth and Grace streets.

“Every night, as soon as Marroni’s and Sepul’s closed,” Mark recalled, “it was a mad scramble up the street to the Oriental. Everybody flew up the street, and ran up the steps. Everybody made a mad scramble to get to the booths that faced on Grace Street. Then we would hang out the window and scream at the ones going by in the cars that were cruising or walking up and down the street. Can you imagine going into a restaurant after the bars closed and hanging out the windows and screaming at cars going by?”

Gays also headed to private parties after the bars closed. “You might have 100 or 125 people milling around drinking beer, but everybody enjoyed everybody,” Mark said. “The gay people were friendlier towards each other then.”

The bar scene at the time was noted for its friendliness, Mark added. “Total strangers would come into the gay bar, and I can assure you that within half an hour there were a half a dozen people to talk to them and make them welcome and find out who they were and have them become part of the community. I’m sorry to say that gay people today have a lot to learn from our experiences. We didn’t have the standoffishness you have now. We were one big community.”

Tags

Bob Swisher

Bob Swisher is a reporter for The Richmond Pride. (1988)