Could Frankencrops be killing the bees?

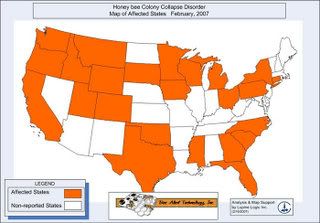

The South is among the regions of the United States hit hard by colony collapse disorder, in which large numbers of honeybees are dying off and disappearing, never to be seen again. The United States in recent months has lost about a quarter of its colonies, five times the typical winter losses.

The South is among the regions of the United States hit hard by colony collapse disorder, in which large numbers of honeybees are dying off and disappearing, never to be seen again. The United States in recent months has lost about a quarter of its colonies, five times the typical winter losses.

The problem, which has also been documented in a number of European nations and Brazil, has enormous implications for food security and the economy, as bees pollinate more than 90 crops, including apples, soybeans, citrus fruit, peaches, blueberries and melons.

Some have blamed pesticides for poisoning the bees. Others have suggested that cell phone radiation could be disrupting the creatures' navigating systems. Yet others have pointed to a fungus.

But as Matt Hutaff notes in an article in The Simon, if pesticides or cell phones were the culprit, we would expect that the bee deaths would be a global phenomenon and would have happened years ago. CCD, on the other hand, was observed in recently months in isolated areas and then spread rapidly. Hutaff suggests another possible trigger: genetically modified crops. He observes:

Most genetically-modified seeds have a transplanted segment of DNA that creates a well-known bacterium, bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), in its cells. Normally Bt is not a problem -- it's a naturally-occurring pesticide that's been used as a spray for years by farmers looking to control crop damage from butterflies. And it's effective at helping beekeepers keep bees alive, too -- Bt is sprayed under hive lids to keep those pesky wax moths from attacking.

But "instead of the bacterial solution being sprayed on the plant, where it is eaten by the target insect, the genes that contain the insecticidal traits are incorporated into the genome of the farm crop," writes biologist and beekeeper John McDonald. "As the transformed plant grows, these Bt genes are replicated along with the plant genes so that each cell contains its own poison pill that kills the target insect.

Canadian beekeepers, for instances, have observed the disappearance of the wax moth even in hives not treated with Bt, presumably due to bees foraging in fields planted with transgenic crops. In addition, a trial of genetically modified crops in the Netherlands reportedly led to CCD in an area within about 60 miles of the test plantings.

It may not be only the transgenic nature of these crops that's to blame: Many seeds from which genetically modified crops are grown are first treated with systemic insecticides that may appear later in the plants' nectar and pollen, notes a University of Florida entomology researcher.

Grist magazine points out that CCD primarily afflicts large-scale bee operations that drive the hives across the country "chasing the bloom," with small-scale honey producers still relatively unscathed. Grist is skeptical that GM crops alone are to blame, speculating instead that a variety of factors -- including GM crops and pesticides -- may be compromising bees' immune systems, making them susceptible to whatever causes CCD. But the article ends on note both hopeful and practical:

The answer to this dire problem is delicious. Support your local foodshed -- and give extra-special love to your local honey producers.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.