Gustav Coverage: Government inaction on coastal protection threatens traditional Louisiana cultures

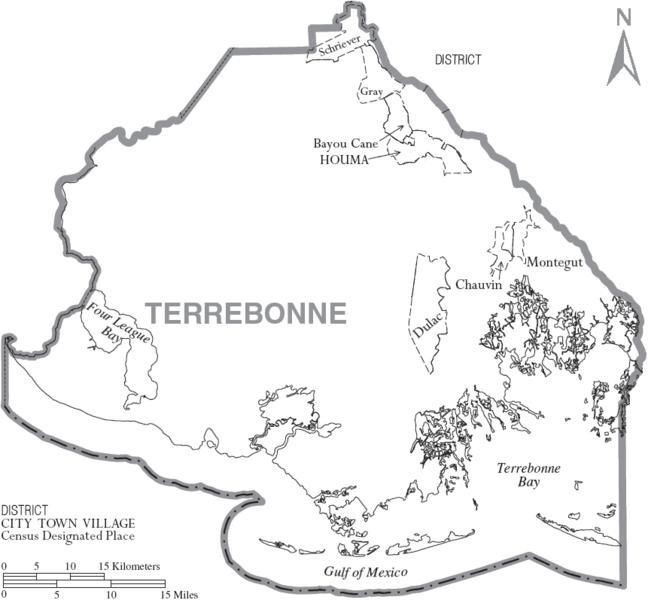

Hurricane Gustav made landfall yesterday southwest of New Orleans in the historically Cajun community of Cocodrie in coastal Terrebonne Parish. Gov. Bobby Jindal says he's received reports of widespread damage in Terrebonne as well as coastal Lafourche and St. Mary parishes, and helicopter crews will be searching the area for the injured and dead.

Hurricane Gustav made landfall yesterday southwest of New Orleans in the historically Cajun community of Cocodrie in coastal Terrebonne Parish. Gov. Bobby Jindal says he's received reports of widespread damage in Terrebonne as well as coastal Lafourche and St. Mary parishes, and helicopter crews will be searching the area for the injured and dead.

Terrebonne residents who stayed through the storm told reporters it was easily the worst they'd ever seen. They questioned whether it was a really just a Category 2.

Ricky Trahan, a 47-year-old shrimper from the Terrebonne community of Chauvin who rode out Gustav on his boat, also told the Times-Picayune that conditions across coastal Louisiana seemed to be getting more dangerous:

"It used to be safe harbor down here," Trahan said. "Not anymore. We keep going further up" the bayou when storms approach.

The increasing danger Trahan is witnessing is due in part to the erosion of coastal wetlands that help soften the blow from tropical storms. And that erosion is due in part to the state's oil and natural gas industries, which are concentrated in Terrebonne and other nearby coast parishes. They have contributed to wetlands erosion by cutting channels in and otherwise developing coastal wetlands for exploration and extraction.

While there are a number of public efforts underway to restore degraded coastal lands and thus better protect Louisiana's residents from storms, none of them comes close to the minimum estimate of $14 billion needed for truly sustainable restoration. If the federal government does not take action soon, the problem will only grow much worse -- and Louisiana's wetlands are already disappearing at the fastest clip in the nation, with up to 40 square miles lost each year.

Tragically, this erosion threatens not only land but traditional cultures tied to that land -- that of Cajun fishers like Trahan, whose name can be traced back to Louisiana's original Acadian settlers, and the indigenous Houma people who live along south Louisiana's bayous and in coastal fishing communities.

Last August, I visited rural Terrebonne Parish to interview United Houma Nation Principal Chief Brenda Dardar-Robichaux about how her community was recovering from Katrina and Rita. The impact of land loss on her community came up in our discussion, as I reported in "Blueprint for Gulf Renewal" (pdf):

"We witness firsthand on a daily basis how coastal erosion affects communities," says Dardar-Robichaux, pointing out that the Gulf of Mexico is now literally lapping at the doorsteps of some tribal members. "It's just a matter of time before some of our communities no longer exist."

As we noted in our recent report titled "Hurricane Katrina and the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement" (pdf), the Guiding Principles -- which the Bush administration has explicitly endorsed -- say governments have a "particular obligation" to prevent the displacement of indigenous people due to manmade or natural disasters. Yet the indigenous people of Terrebonne Parish, and their longtime Cajun neighbors, are watching as the Gulf swallows their land, and their government fails to act.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.