CULTURE BEAT: A Georgia resident's long road to a Pulitzer

By Ken Edelstein, Georgia Online News Service

Once in a very long while, a book comes along that can revise a people's view of their own culture -- not through abstract theories or appeals to ideology, but by constructing a true narrative based on long-forgotten facts and the stories of real people.

Douglas A. Blackmon's Slavery by Another Name, which won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction Monday, is such a book. Those who read it are forced to accept a new understanding of the American South -- that racial injustice was more violent, widespread and recent than most of us realized, and that it played a larger role in the region's economic and cultural development than many Southerners will ever acknowledge.

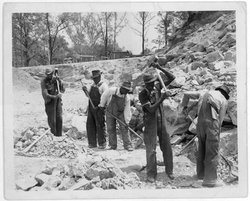

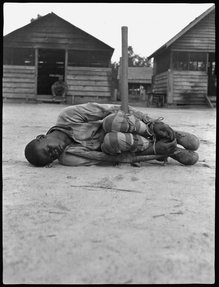

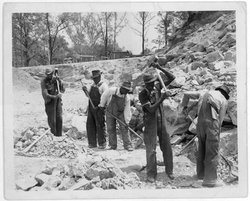

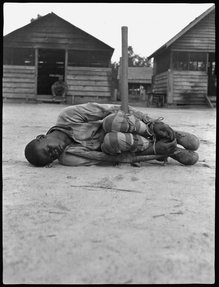

The central thesis is that, contrary to what we learn in the history books, slavery did not end with the Civil War. Rather, it lived on well into the 20th century as an informal, barbaric system that developed hand-in-hand with black disenfranchisement and white profiteering.

Blackmon's masterpiece was a long time coming. In 2001, the Atlanta journalist wrote a lengthy article in The Wall Street Journal on U.S. Steel profiting from conscripted black laborers in Alabama coal mines during the early 1900s. I happened to pick up the Journal that day, because Blackmon's familiar byline caught my eye.

Like other readers, I was gripped by the story. Blackmon had combed deeply enough through Alabama court records and ancient corporate documents to build a tale of widespread cruelty and death, corruption, and social amnesia. He told that tale in a patient, neutral voice, confident that the unembellished truth would be enough to produce a natural outrage.

Shortly afterward, Blackmon started talking about a book that would expand on the same general subject. But he had a day job as deputy Atlanta bureau chief for the Journal, and he was promoted to bureau chief during the time he supposedly was working on this side project. As the years passed, many who knew him (at least those, like me, who would run into him casually) wondered when -- even whether -- the book would be finished.

Slavery By Another Name was worth the wait. It turns out that Blackmon somehow found the time to plug away on his research in county courthouses, online databases and corporate libraries, as well as by interviewing people who were old enough to recount bits and pieces of a history that had never truly been recorded.

Some people actually do hold a collective memory of the ugly chapter that Slavery by Another Name uncovers. At a book signing last year, Blackmon noted that many black Southerners began to tell him during his research (and apparently even more after the book's publication) that they'd grown up with stories of relatives who'd been sentenced to a brief prison term on a minor or even trumped-up charge, only to disappear into the corrupt convict-leasing system, never to return again to their loved ones.

White families, Blackmon noted, didn't pass down such lore: Their relatives seldom fell victim to the system -- so why would they fixate on it? Other whites were the perpetrators -- not the kind of thing you boast about to your children.

But the legacy of a reality forgotten by the majority race lived on. Some families -- among them leading families in Atlanta -- reaped lasting wealth and power out of their exploitation and cruelty. Other families gained only pain and sorrow.

That is one reason Slavery by Another Name is an important book to Southerners, especially white ones. It forces us to revise our understanding of how we got where we now are. Blackmon's book documents that the lore handed down within the South's minority culture truly is the history of us all.