Finding the cost of coal

By Bill Bishop, Daily Yonder

What does coal cost mining communities?

More than it gives in return, according to two new reports. The studies, from Kentucky and West Virginia, both conclude that the benefits of coal mining don't come close to matching its costs.

One of the reports, in fact, finds that coal mining is responsible for lower levels of education, increased outmigration from coal communities, and thousands of premature deaths each year.

The Kentucky study measured the cost of coal to state government. The Mountain Association for Community Economic Development (MACED) counted the revenues to state government from coal mining and coal employment. And it calculated what the coal industry costs the state government: MACED added state-funded benefits, such as tax incentives, and the costs of regulation and road maintenance (repairs to the roads damaged by the large trucks that haul coal).

MACED's analysis concludes that in 2006 coal mining cost the Commonwealth of Kentucky $115 million more in subsidies and expenditures than the state collected in taxes and fees.

MACED included taxes paid by the industry (mostly sales and corporate income) and taxes paid by individuals who were either directly or indirectly employed by the coal industry. (For instance, a cook at a restaurant in a coal community earns part of his salary from meals cooked for those who work in the mines. A portion of the cook's taxes were included as a benefit to the state from coal.)

Coal industry taxes amounted to nearly $528 million in revenues to the state in 2006. But the cost of coal -- including $239 million to maintain and repair coal haul roads -- came to $643 million.

"The estimates presented here suggest that while direct employment in coal by itself is a net benefit both to those employed and to the state of Kentucky, this benefit comes at a significant cost," the MACED report concludes. "The industry itself costs the state more than the industry contributes to public funds and the indirect employment impact, while important, is concentrated in lower wage work such that we do not see a net increase in state revenue."

The full report can be downloaded here.

A spokesman for the Kentucky Coal Association trade group said he hadn't read the study but was sure it was inaccurate. "I've got a lot of choice words that I could offer on this, but it would sound pretty bad," Bill Caylor told the Lexington Herald-Leader's John Cheves. "It's voodoo economics."

The second study comes from researchers at West Virginia University in an article published in the latest issue of Public Health Reports, a scholarly journal. Michael Hendryx and Melissa Ahern examined mortality rates in Appalachian coal mining counties between 1979 and 2005 in an attempt to calculate the cost of coal in the shortened lives of those who reside in mining communities.

They concluded that the "human cost of the Appalachian coal mining economy outweighs its economic benefits."

The full report can be downloaded here.

Hendryx and Ahern found that as the amount of coal mining rose in Appalachian counties, average incomes and education went down. Meanwhile, poverty rates, unemployment rates and mortality rates went up. The researchers were particularly interested in the high mortality rates in Appalachian coal counties. On average over the years of the study, coal mining counties had 3,975 more deaths each year than a similar population of non-coal residents of Appalachia.

The two West Virginia University professors found that these premature deaths in coal communities cost the country $18.2 billion per year.

Age-adjusted mortality rates in coal counties were higher than in other Appalachian counties in every year from 1979 to 2005. The highest mortality rates were in areas with the highest levels of mining -- and over time the gap in mortality rates between coal and non-coal communities had increased.

Hendryx and Ahern wrote that "poverty, low education level, smoking behavior, and environmental pollutants are among the factors that lead to higher mortality rates in coal mining areas. Higher mortality may also be due in part to conditions of elevated stress caused by economic disadvantage and environmental degradation."

It wasn't the mining job itself that caused the higher mortality rates. Men and women alike had elevated rates even though almost all mining jobs are filled by men. The West Virginia University professors wrote that it was the economic, social and environmental atmosphere found in coal communities that led to the higher mortality rates.

If the disparity in mortality rates between coal and non-coal counties could be eliminated, an estimated 3,975 to 10,923 lives would be saved each year.

Hendryx and Ahern found that "socioeconomic disadvantage is a powerful cause of morbidity and premature mortality." Coal counties have higher unemployment and poverty rates than the rest of Appalachia and this "economic disadvantage appears to be a contributing factor to the poor health of the region's population."

One example of the economic weakness of coal mining communities is the continuing outmigration from these places. An average of 639 people moved from each coal mining county in West Virginia between 1995 and 2000. In non-coal counties, an average of 422 people moved in during those same five years.

Both reports came to the same conclusion: coal communities would be healthier and wealthier if they found a way to diversify their economies. "While no one knows for sure how long coal will be mined in Kentucky, it is not a renewable resource," the MACED report concluded. "We must work harder to achieve lasting economic diversification throughout Kentucky and its coalfield communities."

Based in Austin, Texas, Bill Bishop is co-editor of the Daily Yonder, an online source of news, commentary, research and features about the rural United States. It's published by the Center for Rural Strategies in Whitesburg, Ky.

What does coal cost mining communities?

More than it gives in return, according to two new reports. The studies, from Kentucky and West Virginia, both conclude that the benefits of coal mining don't come close to matching its costs.

One of the reports, in fact, finds that coal mining is responsible for lower levels of education, increased outmigration from coal communities, and thousands of premature deaths each year.

The Kentucky study measured the cost of coal to state government. The Mountain Association for Community Economic Development (MACED) counted the revenues to state government from coal mining and coal employment. And it calculated what the coal industry costs the state government: MACED added state-funded benefits, such as tax incentives, and the costs of regulation and road maintenance (repairs to the roads damaged by the large trucks that haul coal).

MACED's analysis concludes that in 2006 coal mining cost the Commonwealth of Kentucky $115 million more in subsidies and expenditures than the state collected in taxes and fees.

MACED included taxes paid by the industry (mostly sales and corporate income) and taxes paid by individuals who were either directly or indirectly employed by the coal industry. (For instance, a cook at a restaurant in a coal community earns part of his salary from meals cooked for those who work in the mines. A portion of the cook's taxes were included as a benefit to the state from coal.)

Coal industry taxes amounted to nearly $528 million in revenues to the state in 2006. But the cost of coal -- including $239 million to maintain and repair coal haul roads -- came to $643 million.

"The estimates presented here suggest that while direct employment in coal by itself is a net benefit both to those employed and to the state of Kentucky, this benefit comes at a significant cost," the MACED report concludes. "The industry itself costs the state more than the industry contributes to public funds and the indirect employment impact, while important, is concentrated in lower wage work such that we do not see a net increase in state revenue."

The full report can be downloaded here.

A spokesman for the Kentucky Coal Association trade group said he hadn't read the study but was sure it was inaccurate. "I've got a lot of choice words that I could offer on this, but it would sound pretty bad," Bill Caylor told the Lexington Herald-Leader's John Cheves. "It's voodoo economics."

The second study comes from researchers at West Virginia University in an article published in the latest issue of Public Health Reports, a scholarly journal. Michael Hendryx and Melissa Ahern examined mortality rates in Appalachian coal mining counties between 1979 and 2005 in an attempt to calculate the cost of coal in the shortened lives of those who reside in mining communities.

They concluded that the "human cost of the Appalachian coal mining economy outweighs its economic benefits."

The full report can be downloaded here.

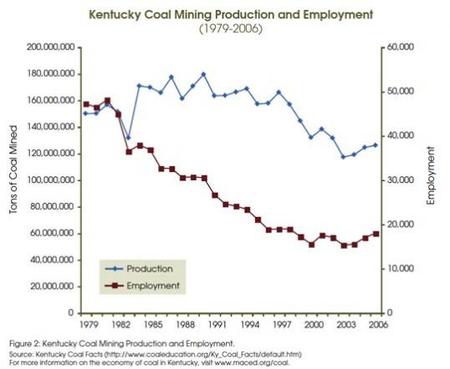

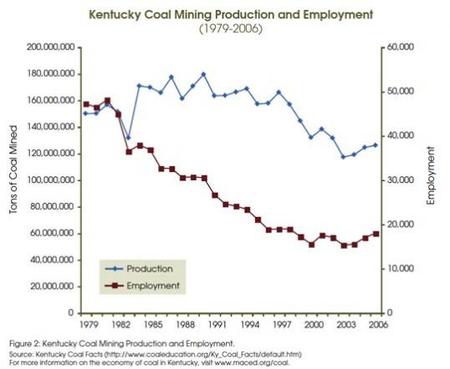

Coal employment has been dropping in Kentucky for years, even as production has remained relatively steady.

Hendryx and Ahern found that as the amount of coal mining rose in Appalachian counties, average incomes and education went down. Meanwhile, poverty rates, unemployment rates and mortality rates went up. The researchers were particularly interested in the high mortality rates in Appalachian coal counties. On average over the years of the study, coal mining counties had 3,975 more deaths each year than a similar population of non-coal residents of Appalachia.

The two West Virginia University professors found that these premature deaths in coal communities cost the country $18.2 billion per year.

Age-adjusted mortality rates in coal counties were higher than in other Appalachian counties in every year from 1979 to 2005. The highest mortality rates were in areas with the highest levels of mining -- and over time the gap in mortality rates between coal and non-coal communities had increased.

Hendryx and Ahern wrote that "poverty, low education level, smoking behavior, and environmental pollutants are among the factors that lead to higher mortality rates in coal mining areas. Higher mortality may also be due in part to conditions of elevated stress caused by economic disadvantage and environmental degradation."

It wasn't the mining job itself that caused the higher mortality rates. Men and women alike had elevated rates even though almost all mining jobs are filled by men. The West Virginia University professors wrote that it was the economic, social and environmental atmosphere found in coal communities that led to the higher mortality rates.

If the disparity in mortality rates between coal and non-coal counties could be eliminated, an estimated 3,975 to 10,923 lives would be saved each year.

Hendryx and Ahern found that "socioeconomic disadvantage is a powerful cause of morbidity and premature mortality." Coal counties have higher unemployment and poverty rates than the rest of Appalachia and this "economic disadvantage appears to be a contributing factor to the poor health of the region's population."

One example of the economic weakness of coal mining communities is the continuing outmigration from these places. An average of 639 people moved from each coal mining county in West Virginia between 1995 and 2000. In non-coal counties, an average of 422 people moved in during those same five years.

Both reports came to the same conclusion: coal communities would be healthier and wealthier if they found a way to diversify their economies. "While no one knows for sure how long coal will be mined in Kentucky, it is not a renewable resource," the MACED report concluded. "We must work harder to achieve lasting economic diversification throughout Kentucky and its coalfield communities."

Based in Austin, Texas, Bill Bishop is co-editor of the Daily Yonder, an online source of news, commentary, research and features about the rural United States. It's published by the Center for Rural Strategies in Whitesburg, Ky.