The South's dangerous drinking water

Millions of U.S. residents are drinking tap water that contains dangerous levels of toxic chemicals -- and many states in the South and elsewhere are doing a poor job of enforcing regulations designed to protect the public from such hazards.

That's the finding of the latest installment in the New York Times' groundbreaking investigation into drinking water safety. Titled "Clean water laws are neglected, at a cost in suffering," it opens with a photograph of extensive dental work in the mouth of 7-year-old Ryan Massey of West Virginia -- work installed after the enamel on his teeth was eaten away by the dangerously high levels of heavy metals in the water at his family's home near the state capital of Charleston. Massey's younger brother has scabs on his body where the water caused painful rashes.

When the boys' parents and more than 260 of their neighbors sued nine nearby coal companies for contaminating the water, their attorney collected reports submitted to the state that revealed the companies were pumping into the ground illegal concentrations of the same chemicals contaminating the water -- but state regulators never took action against the illegal activity.

And as the paper discovered, the problem isn't limited to West Virginia:

The investigation found that fewer than 3% of Clean Water Act violations resulted in fines or other significant punishments by state regulators, and the EPA has often declined to prosecute polluters or take action against lax state regulatory bodies. While scarce resources are one reason for weak enforcement, another is the lobbying might of powerful industries -- like coal mining companies in West Virginia.

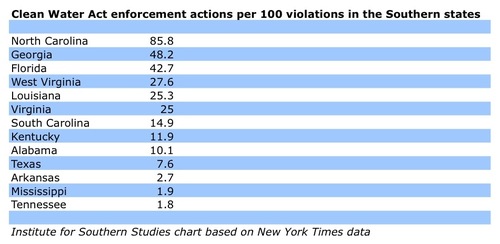

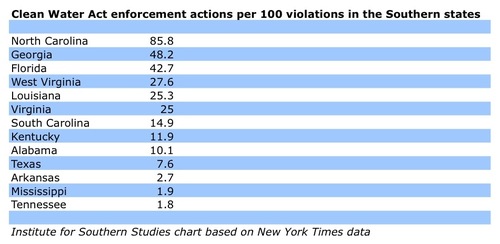

The following chart, based on information from the New York Times' story database, shows the rate of enforcement actions in the 13 Southern states, arranged in descending order:

The serious problems with drinking water in West Virginia come despite what appears to be an above-average record of enforcement. The state actually ranks 10th in the nation in terms of enforcement actions issued per 100 clean water violations.

The serious problems with drinking water in West Virginia come despite what appears to be an above-average record of enforcement. The state actually ranks 10th in the nation in terms of enforcement actions issued per 100 clean water violations.

But as Ken Ward reports at the Charleston Gazette's Coal Tattoo blog, this figure doesn't tell the whole story:

As the paper concludes, it's unlikely the authorities will take steps to toughen enforcement unless there's public outrage over what's happening. If the thought of children's teeth and skin being ravaged by drinking water rendered toxic by illegal waste dumping doesn't spark that, what will?

That's the finding of the latest installment in the New York Times' groundbreaking investigation into drinking water safety. Titled "Clean water laws are neglected, at a cost in suffering," it opens with a photograph of extensive dental work in the mouth of 7-year-old Ryan Massey of West Virginia -- work installed after the enamel on his teeth was eaten away by the dangerously high levels of heavy metals in the water at his family's home near the state capital of Charleston. Massey's younger brother has scabs on his body where the water caused painful rashes.

When the boys' parents and more than 260 of their neighbors sued nine nearby coal companies for contaminating the water, their attorney collected reports submitted to the state that revealed the companies were pumping into the ground illegal concentrations of the same chemicals contaminating the water -- but state regulators never took action against the illegal activity.

And as the paper discovered, the problem isn't limited to West Virginia:

In the last five years alone, chemical factories, manufacturing plants and other workplaces have violated water pollution laws more than half a million times. The violations range from failing to report emissions to dumping toxins at concentrations regulators say might contribute to cancer, birth defects and other illnesses.The New York Times obtained hundreds of thousands of water pollution records through Freedom of Information Act requests and the EPA, compiling a national database of water pollution violations. It reveals that one in 10 U.S. residents have been exposed to drinking water that fails to meet federal health standards. That includes residents of cities with municipal water systems as well as rural communities with wells.

However, the vast majority of those polluters have escaped punishment. State officials have repeatedly ignored obvious illegal dumping, and the Environmental Protection Agency, which can prosecute polluters when states fail to act, has often declined to intervene.

The investigation found that fewer than 3% of Clean Water Act violations resulted in fines or other significant punishments by state regulators, and the EPA has often declined to prosecute polluters or take action against lax state regulatory bodies. While scarce resources are one reason for weak enforcement, another is the lobbying might of powerful industries -- like coal mining companies in West Virginia.

The following chart, based on information from the New York Times' story database, shows the rate of enforcement actions in the 13 Southern states, arranged in descending order:

The serious problems with drinking water in West Virginia come despite what appears to be an above-average record of enforcement. The state actually ranks 10th in the nation in terms of enforcement actions issued per 100 clean water violations.

The serious problems with drinking water in West Virginia come despite what appears to be an above-average record of enforcement. The state actually ranks 10th in the nation in terms of enforcement actions issued per 100 clean water violations.But as Ken Ward reports at the Charleston Gazette's Coal Tattoo blog, this figure doesn't tell the whole story:

We know that the WVDEP went for four or five years -- maybe more -- without even looking at the monthly pollution discharge reports that coal companies file. WVDEP started doing so only after the federal EPA came into the state and won a record $20 million Clean Water Act settlement from Massey Energy. And since then, WVDEP has been entering into private settlements with coal operators, in a move environmental groups say is aimed at avoiding citizen lawsuits that might bring larger penalties and tougher compliance schedules.And while North Carolina had the highest number of enforcement actions nationally, they consisted mostly of small fines, averaging $1,387 per violation, according to the New York Times.

As the paper concludes, it's unlikely the authorities will take steps to toughen enforcement unless there's public outrage over what's happening. If the thought of children's teeth and skin being ravaged by drinking water rendered toxic by illegal waste dumping doesn't spark that, what will?

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.