Matters of life, death and health care in the rural South

In late July, in the heart of Appalachia, thousands crowded onto a southwest Virginia fairground for the annual Wise County free medical clinic led by Remote Area Medical, a volunteer medical relief corps based out of Tennessee. During the clinic's three days of operations, more than 14,000 rural Southern families, most with little or no insurance, spent hours in line to receive free health care from hundreds of professional doctors, nurses, dentists, and other health care workers.

In late July, in the heart of Appalachia, thousands crowded onto a southwest Virginia fairground for the annual Wise County free medical clinic led by Remote Area Medical, a volunteer medical relief corps based out of Tennessee. During the clinic's three days of operations, more than 14,000 rural Southern families, most with little or no insurance, spent hours in line to receive free health care from hundreds of professional doctors, nurses, dentists, and other health care workers.It was a reminder for many that health care reform is not only vital to impoverished urban areas, but it is a crucial matter in much of rural America. Rural America in many ways has become a silent observer to the health care battle taking place in Washington, often left out of the debate and painted with a brush that reads "anti-reform." But there's another story to rural America that often goes untold -- one of poor rural populations struggling to survive with little or no health insurance and being ignored by their elected leaders. It's a story important here in the South, a region that is largely rural and poor.

As Facing South noted before, lost in much of the health care reform debate is what reform would mean to rural communities. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture [pdf], rural areas have been hit hardest by the nation's broken health insurance system:

Individuals living in rural areas are more likely to be uninsured than those in urban areas (24 percent versus 18 percent), although they are 50 percent more likely to have Medicaid coverage. Two-thirds of the uninsured are low- income families, and 30 percent are children. Even those lower income individuals who are working often lack health insurance due to the structure of employment in rural areas--specifically, smaller employers, lower wages, and greater prevalence of self-employment.The Nebraska-based Center for Rural Affairs and the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Community Change recently released a report entitled, "Sweet the Bitter Drought: Why Rural America Needs Health Care Reform," which details the importance of health care reform to rural people and rural communities.

Rural Americans are more likely to be uninsured or underinsured than their urban counterparts, according to the report. The authors of the report highlight that the more than 60 million people who live in rural America have the most to gain from fundamental health care reform. According to the report, rural communities, many of them in the South, have been let down by the private insurance industry. These are the same rural communities that face higher rates of chronic disease, poor nutrition and deaths from injuries than any other region in the country, making access to affordable health insurance a life-saving necessity.

From the report:

...the health care reform debate has suffered greatly from a false dichotomy that ailing urban poor folks are the main beneficiaries of reform, while the hardy rural middle class is healthy and well-served by the current system. The truth is that rural people and rural communities are faced with many of the same health care challenges confronting the rest of the nation--exploding heath care costs, large numbers of uninsured and underinsured, and an overextended health care infrastructure.

...

Rural Americans are more likely to be underinsured, less likely to have choices in private insurance coverage, and in dire need of the medical services and technology that public health care investment has brought to big cities. The majority of rural Americans are suffering silently in our broken health care system and want change now.

James from Union City, Tennessee, put it best: "We're not screaming, we're pleading."The report identifies several health care issues that make health care reform a critical one for rural communities. Rural communities have: an aging, sicker, more at-risk population with less access to preventive health care; a lack of health and wellness resources and centers; a highly-stressed health care delivery system; higher rates of chronic illness (arthritis, asthma, heart disease, diabetes, hypertension and mental disorders); a shortage of practicing physicians, dentists, pharmacists, registered nurses, and emergency medical personnel; and riskier professions (farming and industry).

As the report notes, issues of uninsurance and underinsurance are also more prominent in rural areas:

Since the late 1990s, rural areas have witnessed a significant decline in manufacturing jobs and a rise in service sector employment, losing jobs with higher rates of employer-sponsored health insurance while gaining jobs with much lower rates of such coverage. The lack of employer-sponsored health insurance is particularly acute for low-skilled jobs, which are more common in rural areas.

If they do have coverage, rural populations often pay higher costs for less coverage since rural economies are also heavily based on self-employment and small business, two groups greatly impacted by the rising cost of health care premiums. Almost half of all jobs in rural communities are tied to small businesses, a rate 13 percent higher than in cities and suburbs. Workers at small businesses are twice as likely to be uninsured as other workers. As the report notes: rural people are generally less insured, more underinsured, and more dependent on the high-cost individual insurance market.

Poverty and Health Care

A majority of the country's poorest states are located in the South, and most of the poverty in the South is located in rural areas. In this sense, it is no surprise that states with substantial rural populations have ranked highest when it comes to the percentage of people living in poverty: Mississippi, Louisiana, West Virginia, Alabama, Arkansas,Texas, South Carolina, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia. Most of these states have also ranked highest when it comes to the least insured. As Facing South reported, when divided by region, the greatest populations of uninsured in the United States are mostly likely to be found in the South (18.2 percent).

Researchers continue to link higher mortality rates to lack of insurance. As Facing South reported, having no health insurance means an early death to almost 45,000 people in the United States annually, according to the American Journal of Public Health. Studies also link a lack of insurance to greater health risks, such as hypertension, poor management of chronic illness, and reduced likelihood of receiving preventative and primary care -- all issues disproportionately impacting rural populations in the South.

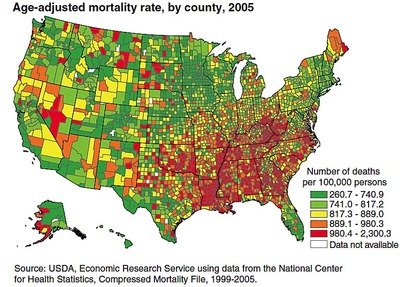

Studies show that rural populations in the South are dying at higher rates than urban populations. Death rates in rural areas are not declining as fast as in non-rural parts of the country, and death rates in the South are also not declining as fast as other regions of the country. The Daily Yonder recently analyzed data from the Economic Research Service and found that the gap between the death rates in rural and urban America has been increasing since 1990.

According to the ERS data, the highest mortality rates are in the rural South, including the Mississippi River Delta, the Black Belt of the southern coastal plain from Virginia through Alabama, and Appalachia (see chart below).

Community groups continue to push for better state and federal policy to tackle these high mortality rates. According to advocates, part of that policy must include support for comprehensive health care reform.

The Politics of Health Care

Yet, when it comes to policy change, rural areas are caught in a particular hard net. Many of these areas are represented in Congress by members who have been most resistant to the Obama administration's push for health care reform and a government-run public option. These politicians -- including Republicans and "Blue Dog" Democrats -- represent districts with the largest percentage of people who don't have health insurance.

A new report by the Urban Institute analyzing uninsurance across congressional districts in the United States illustrates this point. The report finds that rates of private coverage are lowest in districts that have higher poverty rates, which tend to be concentrated in the South and West. The report notes that uninsurance remains most serious in districts with low rates of private coverage.

The report shows that the states and districts that would benefit the most from the passage of health reform are in rural areas and the South (see chart below). Simply put, some of the biggest opponents of health reform in Congress come from districts -- such as ones in Texas and Florida -- with the highest rates of uninsured residents.

As NPR similarly reported in an analysis of the uninsured rates by Congressional district:

Of the 100 congressional districts with the highest percentage rates of uninsured people, 53 are represented either by Republican lawmakers who are fighting the overhaul, or by conservative Blue Dog Democrats who have slowed down and diluted the overhaul proposals.

One leader of the Blue Dog effort is Rep. Mike Ross of Arkansas, the coalition's chief health care negotiator. His 4th Congressional District covers southern Arkansas, a rural area with a high poverty rate. In his district, more than one out of five residents under age 65 lacks health insurance. That's 30 percent higher than the national average.As Facing South reported, Ross claims his opposition to health reform efforts is because "an overwhelming number" of his constituents don't want it. This is a sentiment echoed by other conservative politicians from rural states and districts who claim that rural voters oppose health care reform. But studies continue to show that rural areas have the highest proportion of both uninsured and underinsured, and would benefit the most from comprehensive health care reform that includes a public option.

Related to the politician problem is the fact that rural areas face the heaviest consolidation by the health insurance industry -- meaning there's no competitive market for health insurance in these areas. As Facing South covered, due to unprecedented consolidation of the health insurance market over the past decade, the industry has created near-monopolies in all Southern states, driving up the cost of insurance. These concentrated health insurance markets dominate in predominantly poor rural states like Alabama and Arkansas, whose two largest health insurance companies have a combined market greater than 80 percent in each state.

Politicians like Ross represent states most in need of a public insurance choice to compete with private plans. Lack of competition means rural Southern populations face unaffordable, higher premiums. It also means people are locked out of health care because there are no alternative providers for people who may get turned down for pre-existing conditions (and as we noted above, populations in the rural South have large rates of pre-existing and chronic illnesses).

As NPR reported, a public options would give the uninsured a low-priced alternative to the private companies, and shake up the near-monopolies that insurance companies enjoy in places like rural Arkansas.

Rural health care advocates agree, underscoring that not only is a public option needed to increase competition, it's needed to save lives. "Rural people have much to gain from inclusion of a public health insurance plan option in health care reform legislation, possibly more than any other group in the nation," said Jon Bailey, Director of the Center for Rural Affairs.

As the debate heats up in D.C., more than ever before health care advocates are arguing that health care reform is critical to swaths of the rural impoverished South: from the mountains of Appalachia to the Bible Belt, from the Rio Grande Valley in Texas to the Gulf Coast.

(Images: (1) Patients at the Remote Area Medical free clinic held at the Wise County Fairground in Wise, Virginia; (2) Map of mortality rate by county, Source: ERS; and (3) Uninsurance among non-elderly by Congressional district, Source: Urban Institute.)