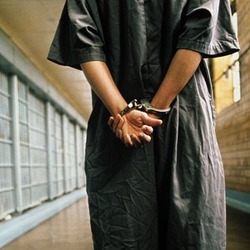

VOICES: Life without parole for teens is uncivilized

By Earl Ofari Hutchinson, New America Media

By Earl Ofari Hutchinson, New America Media

In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court took a huge step toward joining nearly all nations on the globe when it banned teen executions. But it was only a step. The United States still locks up more juveniles for life without the possibility of parole than all nations combined.

The High Court will rule on two Florida cases where juvenile offenders got no-parole life sentences. In those cases as well as tens of others, the crimes they committed did not involve murder. The offenders ranged in age from 13 to 16 years old. There are about 100 juvenile offenders incarcerated for life in eight states with no chance for parole. Nineteen states in all still have no-parole sentences for juveniles on their books.

The 100 offenders who are serving the draconian no-parole sentences though are only the tip of a more terrifying iceberg. A year ago, Human Rights Watch found that more than 2,000 juvenile offenders are serving life without the possibility of parole. A significant number of those juveniles were participants in a robbery or were at the scene of the crime when the death occurred. The majority of the teens slapped with the sentence had no prior convictions, and a substantial number were age 15 or under.

The stock argument against a blanket prohibition against no-parole sentences is that violence is violence no matter the age of the perpetrator, and that punishment must be severe to deter crime. Prosecutors and courts in the states that convict and impose no-parole life sentences on juvenile offenders have vigorously rejected challenges that teen no-parole sentences are a violation of the constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

Hollywood sensationalism and media-driven myths about rampaging youth -- not to mention the very real horror stories of gang violence and young persons who do commit horrendous crimes -- also reinforce the popular notion that juveniles are violent predators. This has done much to damp down public sentiment that juvenile offenders can be helped with treatment and rehabilitation and deserve a second chance rather than a prison cell for life.

This is not to minimize the pain, suffering and trauma juvenile offenders cause with their crimes to the victims and their loved ones. However, a society that slaps the irrevocable punishment of life without parole on juvenile offenders sends the terrible message that it has thrown in the towel on turning the lives of young offenders around. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy hinted at just that in his majority opinion that scrapped teen executions. Kennedy noted that "the punishment of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole is itself a severe sanction, in particular for a young person."

Kennedy acknowledged, as have legions of child violence experts, that juveniles don't have the same maturity, judgment or emotional development as adults. Child experts agree that children are not natural-born predators and that if given proper treatment, counseling, skills training and education, that most juvenile offenders can be turned into productive adults.

In a report on juveniles and the death penalty, Amnesty International found that a number of child offenders sentenced to death suffered severe physical or sexual abuse. Many others were alcohol or drug impaired, or suffered from acute mental illness or brain damage. Nearly all were below average intelligence. Some of the juvenile offenders were goaded, intimidated, or threatened with violence by adults who committed crimes and forced them to be their accomplices.

Then there's the issue of race. Black teens are 10 times more likely to receive a no-parole life sentence than white youths. They are even more likely to get those sentences when their victims are white. This was the case in the two Florida cases the Supreme Court will look at. They are often tried by all-white or mostly-white juries. Those same juries seldom consider their age as a mitigating factor. The racial gap between black and white juvenile offenders is vast and troubling. The rush to toss the key on black juveniles has had terrible consequences in black communities. It has increased poverty, fractured families, and further criminalized a generation of young black men.

The Supreme Court, in its decision to ban juvenile executions, recognized that a civilized nation can't call itself that if it executes its very young. The Supreme Court should recognize that a nation that locks up its very young and throws away the key also can't be called the same. It should scrap the no-parole life sentences for juveniles, too.

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is an author and political analyst. His forthcoming book, "How Obama Governed: The Year of Crisis and Challenge" (Middle Passage Press) will be released in January 2010.