Virginia reawakens the South's Confederate ghosts

When Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell declared April as the state's Confederate History Month, Republican operatives likely thought it was a safe and symbolic gesture that would please the state's older conservatives.

When Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell declared April as the state's Confederate History Month, Republican operatives likely thought it was a safe and symbolic gesture that would please the state's older conservatives. Instead, it's exploded into a national news story, raising sharp questions about how race is used in politics -- and how the South's Confederate past still haunts its political present.

The biggest scandal is what McDonnell's proclamation left out: Not once, in five "whereas" clauses, did it mention slavery. McDonnell batted away criticism about the oversight, saying:

"There were any number of aspects to that conflict between the states. Obviously, it involved slavery. It involved other issues. But I focused on the ones I thought were most significant for Virginia."Which apparently didn't include 4 million African-Americans held in slavery. By the end of the day, after critics including the GOP-inclined Richmond Times-Dispatch denounced him, McDonnell shifted gears and added another clause stating "the institution of slavery led to this war and was an evil and inhumane practice."

But it was too little, too late -- and didn't hide the fact that McDonnell's "omission" wasn't an accident: As Adam Sorensen at Time points out, earlier Republican proclamations for Confederate History Month did include references to slavery; McDonnell just cut them out of his version.

NEO-CONFEDERATES AMONG US

For Southerners, the McDonnell affair is hardly Big News. As historian James Loewen documented in his excellent book Lies Across America, Southern states are filled with thousands of historical markers, tourist sites and other remembrances of the Confederacy that downplay, or entirely omit, the essential racism behind the Confederate project.

The end result is that Southerners grow up surrounded by one-sided history, etched into the very landscape. Attempts to romanticize and rehabilitate the Confederate past can take on near-comical proportions. As Loewen wrote for Southern Exposure magazine in 2000:

Although many Confederates were conquered in spirit in 1865, between about 1890 and 1930, neo-Confederates declared victory on the landscape all across the United States, including places that never existed or never were Confederate during the war. A Confederate monument dominates the lawn of the east Bolivar County courthouse in Cleveland, Mississippi, for example, "To the memory of our Confederate dead, 1861-65." The only problem is, Cleveland, Mississippi, had no Confederate dead. Cleveland did not exist during the Civil War or for some decades afterwards.Even when historically accurate, these ever-present memorials usually go beyond remembering Confederate "heritage" and end up glorifying the Confederacy.

Consider the Arlington Confederate Monument, where even President Obama felt obliged to lay a wreath in 2009, like presidents before him. As leading neo-Confederate scholar Ed Sebesta pointed out in a letter to Obama at the time, the goal of the monument was not just to remember the Confederate dead, but to champion the Confederate cause.

Indeed, the Arlington monument's Latin motto is "Victrix causea Diis placuit, sed victa Catoni." That translates into, "The winning cause pleased the Gods, but the losing cause pleased Cato" -- the implication being that Cato, the stoic advocate of "freedom," would have sided with the Confederacy, a sentiment that descendants of slaves would find deeply ironic.

The same is true with the Museum of the Confederacy, also in Virginia. As Southern Exposure reported in 2000, future President George W. Bush was a donor to the museum's annual Confederate ball, which each year draws hundreds of all-white guests in period costumes.

But the Museum of the Confederacy is hardly an innocent history operation: Its store is stocked with far-right literature on race and politics, including books by neo-Confederate ideologue Ludwell Johnson, who in 1993 was appointed as a "museum fellow" -- author of "Is the Confederacy Obsolete?" and other calls for revival of the old Southern system.

Sometimes, the racial motives of neo-Confederate remembrances are subtle. Other times, they are crystal clear, as with the the decision by white leaders to adopt Confederate flags in Georgia (1956) and South Carolina (1962). Today, historians agree these were moves were timed to protest the growing civil rights movement and its challenge to Jim Crow.

So McDonnell's antics and appeals to Southern white racial resentment are hardly new, or news, in the South.

But the scandal does pose hard questions for conservatives: How will such thinly-veiled racial codes by Southern politicians play out nationally? What does this mean for their efforts to reach moderates and independents?

And as the South and country grow more racially and ethnically diverse, how do appeals to Old South racial politics help conservatives' long-term political prospects?

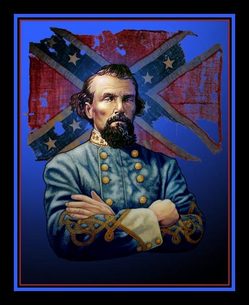

IMAGE: Painting of Nathan Bedford Forrest, leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Tennessee and Confederate cavalry leader. Forrest has more historical markers in the country than any other figure, according to historian James Loewen.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.