Proposed North Carolina voter ID law: A modern-day poll tax?

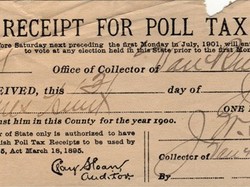

In 1898, when North Carolina Democrats seized control of the state legislature, one of their first steps was to pass an amendment to the state constitution requiring that voters pass a literacy test and pay a poll tax before they could vote.

In 1898, when North Carolina Democrats seized control of the state legislature, one of their first steps was to pass an amendment to the state constitution requiring that voters pass a literacy test and pay a poll tax before they could vote.Then campaigning on a platform of "white supremacy," Democrats insisted the Jim Crow laws -- which, thanks to a "lineage" exception, only applied to blacks -- were necessary to prevent "voter fraud."

But Republicans saw a more sinister agenda at work: According to an 1881 dispatch in The New York Times, written when Democrats first pushed the voting restrictions:

In this way [Democrats] expect to disenfranchise 40,000 Republican voters and make North Carolina a Democratic State for many years.The impact of the voting restrictions was dramatic: Voting participation by African-American males, largely Republicans, plummeted across the South from 98 percent in 1885 to 10 percent in 1905, according to historian J. Morgan Kousser.

Today, voting rights advocates in North Carolina fear that history may be repeating itself. After winning control of the state legislature for the first time since Reconstruction, Republican lawmakers have made it their top legislative priority to pass new election restrictions that require voters to produce photo identification at the polls.

As Bob Hall of the elections watchdog group Democracy North Carolina argues:

Requiring a photo ID is really just a way to reduce the number of voters Republicans don't like. It's exactly what the Democrats did after 1898 ... We're suffering the legacy of that enforced disenfranchisement still today.The True Cost of Voter ID

In 2005, a federal judge halted Georgia's new voter ID law [pdf] on the grounds that it amounted to a new poll tax, because of the costs and burdens it placed on voters. As U.S. District Judge Harold Murphy argued in his 123-page opinion:

The photo ID requirement is most likely to prevent Georgia's elderly, poor and African-American voters from voting. For those citizens, the character and magnitude of their injury -- the loss of their right to vote -- is undeniably demoralizing and extreme.Similar cases from Indiana and other states have made their way to the Supreme Court, where -- under the leadership of Republican appointee Judge John Roberts -- the court has ruled that voter ID laws, while imposing added costs to the voter, are constitutional because the plaintiffs themselves failed to demonstrate they would not be able to get the IDs needed to vote.

But voting rights advocates argue the court's standard is much too narrow: Whatever the case of the individual plaintiffs, they say, millions of voting-age citizens lack any form of photo identification -- studies estimate up to 10 percent, which in North Carolina would amount to over 700,000 people -- and many of them would undoubtedly be prevented from voting if restrictive voter ID laws were to pass.*

Republican advocates of voter ID wave off any notions that it poses a barrier to voters. As Rep. Ric Killian of Mecklenburg County, which includes Charlotte, told the AP:

What's the harm in folks having to show identification to show they're a citizen? That's not too much to ask to participate in this great democracy.But the costs quickly add up. First are the direct costs of purchasing the ID; in North Carolina, a first-time learner permit starts at $15. Don't drive? A U.S. passport card starts at $55.

But as Atiba Ellis of Howard University Law School documents [pdf] in a recent law review article, there are also many indirect costs: the money and time needed to secure documents for the ID, time lost from a job, travel expenses -- costs that grow more significant as you move down the economic ladder, disproportionately affecting the elderly, African-Americans, rural and low-income voters.

Due to this combination of direct and indirect costs, several studies (see here, here and here) have found that voter ID laws end up depressing voter turnout.

To lessen the burden to voters, some states have offered to supply free or subsidized IDs to voters who meet the right criteria. While this lowers some, although not all, of the barriers to the voter, it could cost millions of dollars to the state -- an unwelcome prospect in North Carolina, which currently faces a $3.5 billion budget deficit.

As Keesha Gaskins of the Minnesota League of Women Voters observed in the debate over voter ID laws in her state:

In America we do not permit charging fees to vote. That would be a "Poll Tax," and it's illegal. If we decide to require photo identification for all voters, the state or municipality creating the requirement must provide free photo identification for anyone who requests it, and the taxpayers will have to subsidize the cost. This will require either (1) making drivers' licenses and or photo identification free and pushing the cost to local taxpayers; or (2) creating a new bureaucracy to create voter identification cards, in which case Minnesota taxpayers will have to pay for the creation of an entirely new bureaucratic process.Such costs to state government would be especially hard to justify given that a voter is more likely to be struck by lightning than experience voter impersonation at the polls -- the only alleged voting problem voter ID claims to solve.

But Ellis believes an even bigger issue is at stake: The very idea of voting as a right accessible to all.

Throwing costly and burdensome barriers in the way of voters not only violates that ideal, Ellis says; it also gives politicians dangerous latitude to pick and choose which voters get to participate in our democracy. Or as Ellis argues:

[A]pplying a voter registration regime which depends upon the socioeconomic status of the potential voter creates a dynamic where policy makers can choose what electorate they may wish to have or not wish to have.Which is exactly what North Carolina Republicans said over 100 years ago.

* NOTE: This is the total estimated voting-age population of North Carolina; not all of these residents are eligible to vote, for various reasons.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.