Report: Voter ID law 'unaffordable' for North Carolina

Today, Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies released an analysis [pdf] showing that a voter ID bill proposed by North Carolina Republicans could cost the state $20 million or more over the next three years, exacerbating the state's $3.7 billion budget gap.

Today, Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies released an analysis [pdf] showing that a voter ID bill proposed by North Carolina Republicans could cost the state $20 million or more over the next three years, exacerbating the state's $3.7 billion budget gap.Drawing on data from other states, the Facing South/Institute for Southern Studies report concludes that an effective voter ID program could end up costing North Carolina taxpayers $18 to $25 million over three years, just slightly more than the estimated price tag for a similar measure in Missouri.

The report follows up on a Facing South analysis last week, which documented how GOP leaders are aggressively pushing voter ID bills in at least nine states despite growing evidence that the bills could prove costly to cash-strapped states.

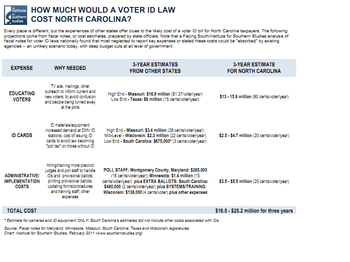

In North Carolina, which faces a budget shortfall of over $3 billion, likely expenses would include::

VOTER EDUCATION: State officials agree that voter ID laws require aggressive publicity efforts to inform voters and ensure they aren't turned away at the polls. In 2010, Missouri estimated it would cost $16.9 million over three years for TV announcements and other outreach to the state's 4 million voters; it could cost North Carolina $14 million or more over three years to inform its 6 million voters.

WHO PAYS FOR I.D.? With studies showing that seven to 11 percent of citizens don't have a photo ID, demands on DMV offices for ID cards will go up -- and so will expenses if North Carolina issues free cards to avoid costly lawsuits claiming the costs of an ID card amount to a poll tax. In 2009, Wisconsin projected a total $2.4 million cost for ID cards; Missouri estimated $3.4 million. In North Carolina, there are reports that a compromise bill would allow voters to use their voter registration cards as a form of ID at the polls; however, the bill would still increase demands -- and costs -- for those requesting ID.

NEW ADMINISTRATIVE AND IMPLEMENTATION COSTS: Voter ID laws add dozens of new costs for state and local officials, from updating forms and websites to hiring and training staff to inspect IDs and handle provisional ballots on Election Day. In 2009, Maryland estimated it could cost over $95,000 each election just for precinct judges in just one county. With agencies strapped for cash, the N.C. legislature would likely need to appropriate millions of dollars each year to help cover these new administrative expenses.

The following chart itemizes the expenses North Carolina would face:

As Facing South reported earlier, these estimates still probably don't reflect the true costs of carrying out a voter ID program. As we found in analyzing the fiscal notes from half a dozen states, most failed to include at least one basic expense needed to implement a voter ID law, such as voter education, administrative expenses and hiring and training additional poll workers.

In other cases, lawmakers acknowledged the added costs, but merely stated they would be "absorbed" by existing agencies -- an unlikely scenario today, given the move to slash budgets at every level of state government.

It's equally clear you can't cut costs on voter ID programs -- not without inviting more problems, and possibly more costs in the long run.

States that don't pay to issue free IDs to those who need them are inviting lawsuits that claim the bill is a poll tax. Failing to spend money up-front for voter outreach and education will only cause a state to pay more later in issuing more provisional ballots to confused voters, and hiring more poll workers to handle those ballots and longer lines on Election Day.

Voter ID laws have always been suspect, given the miniscule number of cases of voter impersonation, and the disproportionate barriers they pose to the elderly, the disabled, students and low-income voters.

But now, with states still economically reeling, costly voter ID laws would seem nearly impossible to justify -- and resistance could escalate quickly once lawmakers realize they simply can't afford them.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.