Gov. Rick Perry flunks civil rights lesson in South Carolina campaign stop

Each presidential election, Republicans declare that this could be the year they might win over African-American voters, or at least enough to tip the balance in key battleground states.

Each presidential election, Republicans declare that this could be the year they might win over African-American voters, or at least enough to tip the balance in key battleground states.But if surging White House hopeful Gov. Rick Perry of Texas ends up clinching the GOP nomination, he may have irreparably hurt his chances of luring black voters -- already a challenge when facing President Obama -- this past weekend at a campaign stop and fundraiser near Rock Hill, South Carolina.

During the media presser, a TV reporter noted that Perry was visiting a "very important place in Rock Hill's and the nation's civil rights history," it being the 50th anniversary of a historic sit-in by a group of students from nearby Friendship College, known as the "Friendship Nine."

But when asked to comment, Perry abruptly shifted from talking about civil rights to pushing his campaign themes of small government:

Listen, America's gone a long way from the standpoint of civil rights and thank God we have. We've gone from a country that made great strides in issues of civil rights, I think we all can be proud of that. And as we go forward, America needs to be about freedom. It needs to be about freedom from overtaxation, freedom from over-litigation, freedom from over-regulation. And Americans, regardless of what their cultural or ethnic background is, they need to know that they can come to America and you got a chance to have any dream come true because the economic climate is gonna be improved.Here's a video of the press conference:

The off-topic response was especially odd given the importance of the Friendship Nine to Southern civil rights history. Following a wave of sit-ins across South Carolina and the South, in January 1961 10 black youth -- nine students from Friendship College and Thomas Gaither, a field secretary for the Congress for Racial Equality -- sat down at a segregated McCrory's Variety Store in Rock Hill and refused to leave.

As usual, the 10 were arrested. But instead of paying bail and getting back in the field, the Rock Hill activists took a different course: All but one refused the NAACP's offer to pay bail, and instead stayed in jail. On February 1 -- exactly one year after North Carolina's famous Greensboro sit-ins -- they were sentenced to 30 days hard labor at the York County Prison Farm. Several were placed in solitary confinement for singing "disruptive" spirituals and freedom songs.

The Friendship Nine electrified the movement. Hundreds of activists from CORE, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups descended on Rock Hill in solidarity.

Their decision to choose "Jail, No Bail" would also prove a decisive turning point in civil rights history. It signaled a new commitment by activists to suffer personal costs for the causes. As historian Dr. Adolphus Belk pointed out in a recent documentary, refusing to pay bail -- and making local officials pay for incarceration -- also shifted the financial costs of civil rights protest onto the Southern power structure:

[The Friendship Nine] shifted all of the responsibility, the financial burden, of imprisonment from the organizations elsewhere. In the process, no longer are they filling the coffers of the people who are imprisoning them and who are erecting these systems to support segregation and Jim Crow.The Friendship Nine struggle also helped inspire the historic Southern Freedom Rides. It was Tom Gaither, the CORE activist who was arrested with the Friendship students, that proposed black and white activists ride together on Greyhound and Trailways buses through the South to dramatize how local policy had failed to catch up with federal desegregation rulings.

The first stop of the now-legendary Freedom Rides in May 1961? Rock Hill, South Carolina, where now-Rep. John Lewis (D-GA) and Albert Bigelow were brutally beaten at the local bus station by a white mob -- the first episode of violence in the rides that would shake the nation and force a reluctant Kennedy administration to step up civil rights enforcement.

In 2008, Rep. Lewis went to Rock Hill, where white mayor Doug Echols formally apologized on the city's behalf for Lewis' treatment there -- showing an understanding of the Friendship Nine's civil rights legacy that goes much deeper than Gov. Rick Perry's.

Historians note that the revived sit-in movement and Freedom Rides in 1961 had another result: they heightened visibility, coordination and influence of the "big three" civil rights groups -- CORE, SNCC and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference -- helping build their capacity for future actions like the massive 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

What were the goals of the historic 1963 march, best known for Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr's "I Have a Dream" speech? The flyer announcing the event, headlined by John Lewis and others, spells out an agenda including these items:

* "[P]assage of civil rights legislation which will guarantee to all decent housing, access to all public accommodations, adequate and integrated education and the right to vote."Many of those issues are still very relevant today. But does that look anything like Rick Perry's agenda for the country in 2012?

* "[A] federal massive works and training program that puts all unemployed workers, black and white, back to work."

* "A national minimum wage, which includes all workers, of not less than $2.00 an hour." [NOTE: That's $14/hour in 2010 dollars]

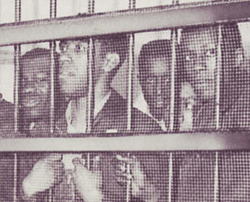

IMAGE: Photo of the Friendship Nine behind bars (Courtesy of Friendship College)

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.