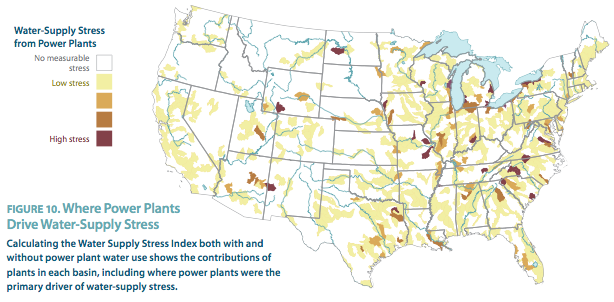

South's power plants stressing drinking-water supplies

When you think about regions of the United States where drinking-water supplies are a pressing concern, the desert Southwest is likely to come to mind. But a new peer-reviewed report from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) details big stresses on the Southeast's watersheds from power plants -- and makes the case for smarter planning.

"Some of the watersheds our analysis identified -- in places like Texas -- should come as no surprise," says lead researcher Kristen Averyt of the University of Colorado Boulder. "But unlike in arid regions, where many power plants have already minimized their water use, we found indicators of potential problems in seemingly water-rich regions like the Southeast."

The report, titled "Freshwater Use by U.S. Power Plants: Electricity's Thirst for a Precious Resource" is the first systematic look at how power-plant cooling affects water resources nationwide -- both quantitatively and qualitatively. The research was carried out by the Energy and Water in a Warming World Initiative, a research collaboration between UCS and a team of more than a dozen scientists.

The report found that the nation's thermoelectric plants -- those that boil water to create steam to drive turbines to generate power -- withdrew as much water in 2005 as all of the nation's farms and four times as much as all U.S. residents. It also found that nuclear power plants draw about about 11 percent more water per unit of electricity generated than coal plants, and a whopping eight times more than natural gas plants.

While power plants in the West tend to rely on aquifers for their water needs, most of those in the East rely on surface water from rivers and lakes -- in many cases the same rivers and lakes that provide drinking water for large communities.

At the same time, plants in the East generally withdraw more water for each unit of electricity produced than plants in the West, which are more likely to use water-saving technologies such as recirculating or dry cooling. What the report calls "freshwater withdrawal intensity" was at least 41 times greater in Virginia and North Carolina than in Utah, Nevada and California.

Consequently, big problems arise when drought strikes. During the drought that afflicted the Southeast in 2007, for example, Duke Energy was forced to cut output at its G.G. Allen and Riverbend coal plants on the Catawba River because of a lack of cooling water, and it struggled to keep the water intake system for its McGuire nuclear plant near Charlotte, N.C. underwater. And for three of the last five years, TVA's Browns Ferry nuclear plant in Alabama had to dramatically cut power output to avoid exceeding the temperature limit on discharge water and killing fish in the Tennessee River.

Meanwhile, as the extreme drought drags on in Texas, one power plant in the state has been forced to cut output while others have had to pipe in water from new sources. If the record-breaking drought persists into next year, as experts predict could happen, several thousand megawatts of electrical capacity might have to be shut down.

"It isn't just coal or natural gas that powers the nation," Averyt observes. "It's water that keeps the lights on."

The UCS report also found serious shortcomings with the data available on power plants' water usage. The researchers relied on figures from the federal Energy Information Administration, part of the Department of Energy, but discovered the data was full of holes and errors.

“We had to piece together a lot of information to get a better handle on how much water power plants were really using," says John Rogers, the report’s co-author and a senior UCS analyst.

With the Southeast's rapid population growth expected to continue over the next decades, demand for both power and drinking water will increase. At the same time, our changing climate is expected to bring more intense droughts to the region.

All of that means it's more critical than ever to make water-smart energy choices. For example, when Georgia Power's Plant Yates near Newnan, Ga. added cooling towers in 2007, it cut water withdrawals from the Chattahoochee River by 93 percent, according to the report.

"Every time we build a power plant, we're making decisions that last for decades," says Peter Frumhoff, director of science and policy at UCS and head of the report's scientific advisory committee. "By investing in power plants that are efficient, use low-water cooling and produce little or no carbon emissions, utilities and plant owners can help protect the water resources our kids and grandkids will depend on, and public utility commissions can encourage or require them to do so, especially where research indicates that power plants place water resources at risk."

(Map graphic from "Freshwater Use by U.S. Power Plants." Click on image for a larger version.)

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.