North Carolina gets a Texas-sized warning on fracking

As North Carolina lawmakers prepare to pass a bill as soon as this week legalizing fracking for natural gas, they got a visit from a former Texas mayor who shared his cautionary tale about the serious problems the industry brought to his small town.

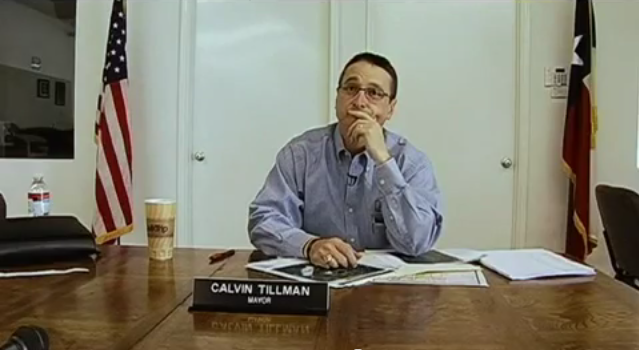

Calvin Tillman was elected mayor of Dish, Texas -- a community of about 200 residents 25 miles north of Fort Worth -- in 2007, at a time when fracking was booming in the area. Dish sits atop the Barnett Shale, which is one of the largest natural gas fields in the United States. Ten massive pipelines run through the town, carrying about a billion cubic feet of gas per day.

Tillman spent much of his time in office fighting to regulate the gas companies, which transformed his once-quiet community into a noisy, polluted industrial center. He finally moved away last year after his two young sons began waking in the middle of the night with severe nosebleeds that the family believes were related to toxic air emissions from the drilling operations.

Before Tillman left, he offered to rent his home to a gas company executive so they could see what it was like to live in the industry's midst.

"None took me up on it," he says.

Tillman, who appeared in the award-winning fracking documentary "Gasland," now works with a nonprofit group he founded called ShaleTest, which does environmental testing for lower-income families and communities affected by natural gas drilling. He visited North Carolina this week to talk about his experiences, meeting with about a dozen state lawmakers.

"I want to let everybody know there's more to this than they're being told by the industry," he says.

Tillman was no stranger to oil and gas drilling when he arrived in Dish in 2003 following service in the military. He grew up in Oklahoma, where his father worked for a time on oil rigs, and he attended high school in a town called Oilton, where he witnessed firsthand the industry's boom-bust cycles.

Tillman was elected to serve as a town commissioner in 2005, when Dish was still known as Clark. (It changed its name that year as part of a deal to get free TV service for residents from the Dish Satellite Network.)

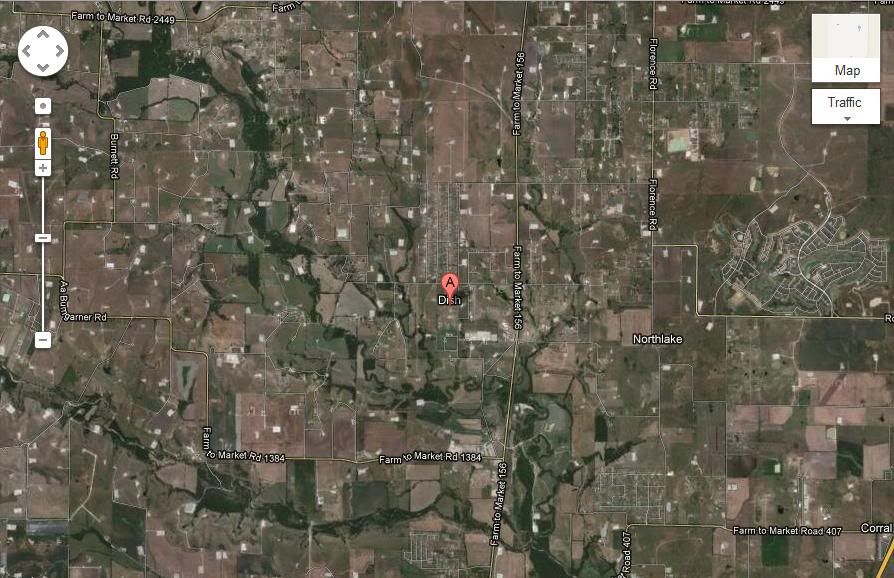

It was around that time that fracking, as Tillman puts it, "went berserk" in the area. This satellite photo shows numerous white rectangles in and around the community -- all of them gas-industry operations (click on photo for a larger version):

Especially worrisome for Tillman and other residents of Dish was the air pollution coming from the operations, including a gas treatment facility near Tillman's home. As production intensified, the chemical stink from the facility grew stronger.

"The odor got to the point where it was uncomfortable to be outside," he says. "Your eyes would be burning."

It was around this time that his sons -- now 7 and 9 -- began experiencing severe nosebleeds even in their sleep, when the problem couldn't be explained by rough play. Tillman also began hearing other residents' stories about nosebleeds that seemed to correlate with the intensity of the odors.

Tillman tried to work with the industry to address the problem. Their solution involved sending a worker out to drive around town for a few hours with a methane detector, after which they declared there was no problem.

Disgusted with the industry's inaction, Tillman contacted a local environmental consulting firm called Wolf Eagle Environmental. The town contracted with the company to conduct a serious air pollution study -- and its conclusions were disturbing:

"Air analysis performed in the Town of DISH confirmed the presence in high concentrations of carcinogenic and neurotoxin compounds in ambient air near and/or on residential properties. The compounds in the air indicate quantities in excess of what would normally be anticipated in ambient air in an urban residential or rural residential area."

Many of the toxic compounds were detected at levels higher than those set by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) for short- and long-term health effects.

Among the chemicals the study found at dangerously high levels were benzene, a known cancer-causing chemical that was detected in one sample at 55 times the Texas standard for long-term health effects. Naphthalene, a potential human carcinogen, was found at levels 3.6 times the standard. Detected levels of xylenes, potent neurotoxins, were double the long-term health standard.

Other chemicals found at levels exceeding TCEQ's health standards were dimethyl sulfide, methyl ethyl disulfide, ethyl-methyl-disulfide, trimethyl benzene, 1,2,4-trimethyl benzene, carbonyl sulfide, carbon disulfide, methyl pyridine and dimethyl pyridine.

In response, TCEQ conducted its own study, testing blood and urine samples from 28 people living in or near Dish. While it did find elevated levels of some toxic compounds in people's bodies, it attributed those to other exposures such as cigarette smoking and household cleaning products. However, TCEQ acknowledged that its study had limitations -- including the fact that it was based on a one-time sample even though the compounds of concern typically stay in the body for only a few hours.

TCEQ's findings did not assuage Tillman's worries. When his sons suffered three severe nosebleeds in the middle of the night during a single week in late May 2010, he decided to leave. In March 2011 the family moved to Aubrey, Texas -- 15 miles from the nearest gas well. Since then, he reports, his sons have not experienced a single middle-of-the-night nosebleed.

But it's not only the health impact of fracking that upset Tillman. As a conservative who was a registered Republican until he became disgusted over former Vice President Dick Cheney's role in securing the "Halliburton loophole" exempting fracking fluid ingredients from disclosure under environmental laws, Tillman is offended by the impact the gas industry has on private property rights. He says that the bill North Carolina is considering is especially troubling on that front.

"This is an atrocity for private-property rights," says Tillman, now a political independent. "Anyone who votes for this bill should have to hand in their conservative cards and take Ronald Reagan's picture off their wall."

He points to the section of N.C. Senate Bill 820 that authorizes what's known as "forced pooling," a controversial legal tool that allows drillers to gain access to mineral rights beneath someone's property without his permission, as long as a certain percentage of his neighbors sign gas leases.

"This is the worst forced pooling bill I've seen," Tillman says. "Your state is giving corporations the authority to come and take your property from you."

He also points out that North Carolina's bill takes away local governments' ability to regulate fracking in their communities -- an insult to his conservative belief in local control.

Tillman urges North Carolina lawmakers to give more careful consideration to what they're getting the state into. But that's looking increasingly unlikely, with the House Environment Committee approving the bill without public comment the morning after Tillman flew back to Texas. The full House is expected to take up the bill -- a version of which has already passed the Senate -- as early as today.

"Everybody needs to slow down," Tillman warns. "The shale's been down there for a million years, and it'll still be there in a million more."

(Photo of Tillman is a still from "Gasland.")

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.