Voting Rights Act key to rolling back new voting restrictions in the South

Over the last two weeks, voting rights advocates have scored a string of victories in Florida and Texas -- and may soon in South Carolina. The key to their success: a provision in the 47-year-old Voting Rights Act, which itself may not survive a recent escalation of legal challenges.

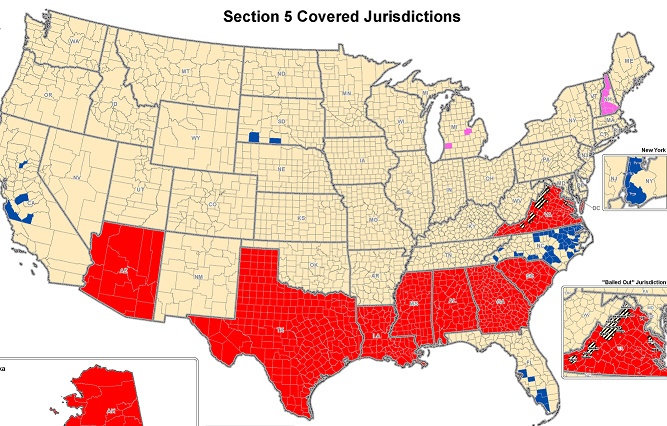

Section 5 of the Act, which demands that any major changes to elections -- including voter ID laws, redistricting and more -- must be pre-cleared in all or part of 16 states, nine in the South.

Section 5 only covers five counties in Florida, but that was enough for the Justice Department to intervene when the state passed a host of new restrictions on voting in 2011. On Aug. 17, 2012, a three-judge panel ruled against one of the provisions, which reduced the state's early voting period from 12 to eight days, saying that it would disproportionately impact minority voters.

The Florida law allowed local election officials to offer early voting anywhere from 48 to 96 hours over the new eight-day voting period. The federal judges said they'd only allow the law to stand if officials opted for the maximum 96-hour period.

In Texas, another three-judge panel -- including appointees from the Clinton, Obama and first Bush administration -- unanimously voted [pdf] to block the state's new voter ID law, which had been tied up in litigation for months.

The federal judges said the Texas law “would lead to a retrogression in the position of racial minorities with respect to their effective exercise of the electoral franchise," a conclusion they said "flows from three basic facts:"

(1) a substantial subgroup of Texas voters, many of whom are African American or Hispanic, lack photo ID; (2) the burdens associated with obtaining ID will weigh most heavily on the poor; and (3) racial minorities in Texas are disproportionately likely to live in poverty.

As Ari Berman writes at The Nation, the Justice Department had marshalled a significant body of evidence to support the claims of disproportionate impact:

[Texas] admitted that between 603,892 to 795,955 registered in voters in Texas lacked government-issued photo ID, with Hispanic voters between 46.5 percent to 120 percent more likely than whites to not have the new voter ID; to obtain one of the five government-issued IDs now needed to vote, voters must first pay for underlying documents to confirm their identity, the cheapest option being a birth certificate for $22 (otherwise known as a "poll tax"); Texas has DMV offices in only eighty-one of 254 counties in the state, with some voters needing to travel up to 250 miles to obtain a new voter ID. Counties with a significant Hispanic population are less likely to have a DMV office, while Hispanic residents in such counties are twice as likely as whites to not have the new voter ID (Hispanics in Texas are also twice as likely as whites to not have a car).

Gov. Rick Perry (R) called the decision "yet another example of the Obama administration's continuing and pervasive federal overreach," and said the law's ID requirements were "nothing more extensive than the type of photo identification necessary to receive a library card or board an airplane."

In their opinion, the justices had already issued their rejoinder to comparing the franchise to everyday consumer transactions:

As the Supreme Court has 'often reiterated…voting is of the most fundamental significance under our constitutional structure.' Indeed, the right to vote free from racial discrimination is expressly protected by the Constitution.

But the Texas case includes a bigger challenge to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act itself, which has barely survived a series of growing legal challenges. The state of Texas argued that if Section 5 prevents its ID law from taking effect, the law is unconstitutional. The judges put that decision off to a later date, allowing Section 5 to dodge another bullet.

Meanwhile, in D.C., a federal judge panel also continued to hear testimony over a recent voter ID bill passed in South Carolina, where last fall the Justice Department began its push-back against voter ID measures.

The case has gone badly for South Carolina. When the law's author, State Rep. Alan Clemmons (R), denied that the bill was motivated by any desire to hurt minority voters, civil rights attorney Garrard Beeney presented evidence that Rep. Clemmons had responded positively to a racist email from one of his constituents about the bill.

In another embarrassment, Sen. George "Chip" Campsen III -- another GOP supporter of the legislation -- testified at length about alleged cases of fraud he had heard about. But when asked by Justice Department attorney Anna Baldwin if any of the instances of fraud related to voter impersonation -- the only kind that voter ID addresses -- Campsen was forced to admit they didn't, and were therefore irrelevant to the case at hand.

Legal analysts now speculate that the only way the South Carolina law may survive is because of the state's ambiguity about how it will enforce it. On Aug. 28, South Carolina election director Marci Andino surprised the court when she said that voters without ID would still be allowed to vote if they could show they had a "reasonable impediment" to getting an ID card, such as lack of transportation to get to the DMV office.

As National Public Radio reported, one of the judges asked if all of South Carolina's voters without ID could claim to have a reasonable impediement to getting one, given that the election is only two months away? "Yes, that's possible," Andino replied.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.