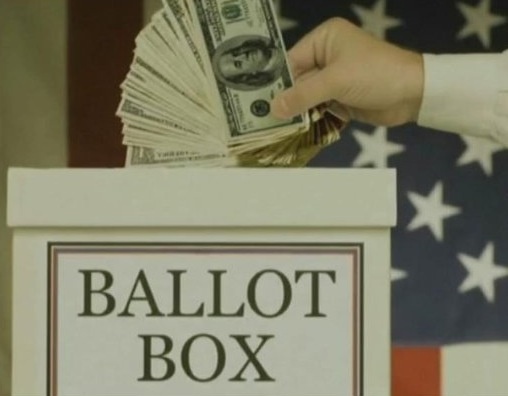

McCutcheon and the two-pronged attack on voting rights

Rev. William J. Barber, the most visible civil rights leader in North Carolina today, stood in front of the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. this week as the court heard arguments on whether campaign contribution limits are constitutional. The president of the North Carolina conference of the NAACP and architect of the Moral Monday movement was speaking at a rally organized by a coalition of groups asking the court to maintain the limits as a way of protecting democracy from corruption.

While he was there to discuss McCutcheon v. FEC, Barber also referenced another case.

"A few months ago, this court, on a day that shall live in infamy, gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the crown jewel of the Second Reconstruction movement my parents and grandparents fought for," said Barber. An "extremist anti-democracy faction" in North Carolina’s state legislature, he said, "celebrated the infamous Shelby decision by rolling out the worst voter suppression bill in the country, and they are just waiting to see what the court will do here."

With arguments in McCutcheon concluded, it seems that the court will most likely strike or at least modify the biennial aggregate limits imposed on individual donors to candidates, parties and political committees. Those limits right now stand at $123,200, which includes a $48,600 cap on donations directed to candidates and restrictions on the number of candidates a single donor can contribute to. But if the aggregate caps are lifted, then one could send the maximum contribution of $2,600 per candidate to all 435 House and 33 Senate races, and a bunch more to state and national parties, to the tune of $3.6 million. That amount could then be "churned" and steered by fundraising committees to specific candidates who would be well aware of who made the large donation.

The Supreme Court ruling on this has "the clear potential to bring about a new constitutional order in campaign finance, in which the very rich might gain even more influence," Lyle Denniston wrote for SCOTUSblog following the McCutcheon arguments.

Given that civil rights and voting rights advocates like Barber are still reeling from the Shelby ruling that severely compromised the Voting Rights Act, they are hyper-aware of the compounded burden on voters of color and low income if their votes are weighed even less against the influence of wealthy donors. NAACP general counsel Kim Keenan has called this "the two-pronged attack on voter participation against regular people in America."

"First, powerful and wealthy donors seek to buy as many leaders as they can through enormous contributions," said Keenan, "then the politicians bankrolled by those donors advance legislation that suppresses the votes of the people who might object."

At the McCutcheon rally, Craig Rice, vice president of Montgomery County, Maryland’s county council, reiterated this view.

"As a young minority elected official, let me tell you, this [case] is extremely troubling," said Rice. "Young minority candidates throughout this country are routinely outspent and therefore denied the ability to serve in elected roles."

George Washington University campaign finance law professor Spencer Overton explained in an interview how a ruling in favor of McCutcheon could harm people of color running for office.

"For candidates who are new, who might be challenging the status quo, what will happen is you will have joint fundraising committees collecting $3 million checks from people who are wealthy and that money will be steered to incumbents, so that's going to be a problem that will adversely affect candidates of color," he said.

In his blog at Huffington Post, Overton illustrated how joint fundraising committees operate based on of his own experience working with one for the Obama campaign last year:

…[W]e initially collected individual checks of up to $35,800 each, which eventually rose to $75,800 (as it did for the Romney campaign). Federal law allowed us to collect a single $75,800 check made out to a joint fundraising committee -- $2500 of which was allocated to the Obama campaign primary election, $2500 to the Obama campaign general election, $30,800 to the Democratic National Committee, and $40,000 to state parties. ...

When a $2500 donor becomes unreasonable, it is relatively easy for a fundraiser to push back. … Pushing back on a $2.95 million contributor, however, would be much more difficult. In short, $2.95 million contributions would lead to a great deal of quid pro quo corruption.

They would also place candidates of color at a disadvantage, said Overton, given the racial wealth gap in America.

"In the pool of people who can make the $3 million contributions, there won't be many African Americans who can make that kind of donation," Overton said in the interview. "So politicians will lean toward those who can make those $3 million contributions, and will have less reason to respond to average voters."

Solicitor General Donald Verrilli testified in his arguments yesterday about how $3 million-plus donations could be juggled around in corrupt ways. But Justice Samuel Alito voiced skepticism, saying that such fundraising schemes "are wild hypotheticals that are not obviously plausible and lack certainly any empirical support."

The Center for Responsive Politics disagrees, reporting this week that "state parties and hundreds of candidates already transfer large sums of money to each other, using the national party groups as hubs."

Barber couldn't possibly have heard what was being said inside the court building yesterday while he was participating in the rally, but he prophetically addressed Alito's skepticism in his speech. He explained how Art Pope, a leading Republican donor who now serves as the North Carolina budget director, has poured money into "propaganda organizations" and "campaigns for many extremist candidates."

"So when we talk about what money can do in North Carolina, it's not theory," said Barber. "We know firsthand that when you undermine laws that guard against voter suppression and you undo regulations on the ability of corporations and individuals to spend unchecked amounts of money to influence and infiltrate and literally to infect the democratic process, it has extreme impact."