In North Carolina, commemorating an innovative strategy in the war on poverty

Community leaders and residents gathered in Durham, N.C. this week to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the North Carolina Fund, a groundbreaking nonprofit created by Gov. Terry Sanford to fight poverty and dismantle racial segregation across the state.

At the time of the fund's creation, 37 percent of North Carolina residents lived in poverty, half of all students dropped out of high school, and a quarter of the state's population was effectively illiterate. Sanford, a liberal Democrat elected governor in 1960, faced resistance in tackling those problems from a legislature dominated by conservative Democrats.

At the urging of his friend John Ehle, a writer and UNC professor known for his fiction set in Appalachia, Sanford visited New York to meet with officials from the Ford Foundation, which at the time was funding model anti-poverty programs. After six months of negotiations, the foundation agreed to fund its first statewide anti-poverty program in North Carolina, providing $7 million under the condition that the program be dissolved after five years.

The North Carolina Fund was incorporated in July 1963. It got additional support from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, and the federal government.

The Fund went on to spend more than $16 million in what director George Esser described as a "quest for new ways to enable the poor to become productive citizens, to encourage self-reliance, and to foster institutional, political, economic, and social change designed to strengthen the functioning of democratic society."

Its programs included manpower development, community action, education and research, all aimed at fighting poverty. Of the original Ford grant, $2 million went to the state Department of Public Instruction to improve elementary schools. The Fund also supported 11 community action agencies across the state, 10 of which still operate today. And it launched other organizations including the Foundation for Community Development, the N.C. Low Income Housing Development Corp., and the Manpower Development Corp., now known as MDC Inc.

But the Fund's work was not without controversy. Congressman Jim Gardner (R-N.C.), who went on to serve as lieutenant governor, criticized the Fund as a "political organization, meddling in the affairs of local communities."

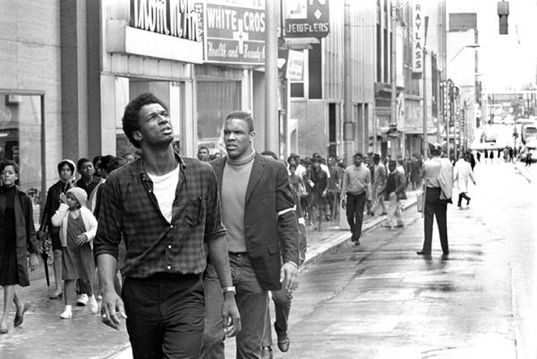

It also ruffled feathers of the African-American elite in places like Durham, recalled Howard Fuller, now a professor of education at Wisconsin's Marquette University. Fuller came to North Carolina in 1965 to work as an organizer with a Fund project called Operation Breakthrough, which continues its anti-poverty work today. Fuller went on to become the Fund's lead organizer, and under his guidance the Fund's organizing strategy shifted from an effort to improve social service delivery to a more militant approach that challenged the local power structure by focusing not just on race but also on class.

"We caused issues for the traditional black leadership," Fuller said during a packed lecture on the Fund held this week at MDC's offices in Durham.

The Fund served as an inspiration for President Johnson's War on Poverty. It also provided a model for the Head Start early childhood education program and the VISTA national service program.

During Fuller's talk at MDC, Bob Korstad, a Duke University professor of public policy and history and co-author of a book titled "To Right These Wrongs: The North Carolina Fund and the Battle to End Poverty and Inequality in 1960s America," noted that the state is facing many of the same challenges today. For example, after falling to a low of 12.3 percent in 1999, North Carolina's poverty rate has climbed to almost 18 percent, and a state legislature dominated by conservative Republicans has proven reluctant to tackle the problem.

Korstad asked Fuller if he could offer any lessons for organizers today. But Fuller was reluctant to give advice, instead quoting philosopher Frantz Fanon: "Each generation must discover its mission, fulfill it or betray it, in relative opacity."

While we may see similar problems now, Fuller said, they are manifesting under different historical conditions. He also pointed out that organizers today have different tools to work with than his generation did.

"You've got to figure out how you're going to wage struggle," Fuller said.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.