The power of Southern song: How the South shaped Pete Seeger

Before he became a folk music legend, Pete Seeger wanted to be a journalist. It was this perspective as a reporter and storyteller that defined Seeger's approach to singing and playing music: sounding out a warning about injustice, introducing us to new people and perspectives, and reconnecting us to our own, often hidden traditions of ordinary people struggling for change.

Seeger, who passed away Jan. 27, took pride in learning and sharing songs from around the world, but no place seemed to shape the New York native, both musically and politically, more than the U.S. South.

In 1936, at the age of 17, Seeger's father -- then working for the New Deal's Works Progress Administration -- took Pete to a folk festival in Asheville, N.C. It was here that Seeger heard Samantha Bumgarner play five-string banjo for the first time and fell in love with the instrument. He also discovered North Carolinian Bascam Lamar Lunsford, the "Minstrel of the Appalachians" who ran the festival and taught Seeger his signature cascading finger-picking style.

After dropping out of Harvard, Seeger's first job was working for Texan folkorist Alan Lomax to catalog and record folks songs for the Library of Congress. Through Lomax, Seeger met his longtime compatriot Woody Guthrie and was exposed to Southerm musicians like Louisiana blues legend Lead Belly and Kentucky labor singer Aunt Molly Jackson who would shape his musical and political outlook.

The Cultural Front

While in New York, Seeger joined a vibrant circle of musicians active in left-wing causes. Among Seeger's closest comrades in the "Cultural Front" was Lee Hayes, the towering labor singer from Arkansas who provided a link for Seeger to both Southern music and the often-hidden history of the region's progressive movements. (Jeff Sharlet has an excellent piece about Hayes in the Oxford American.)

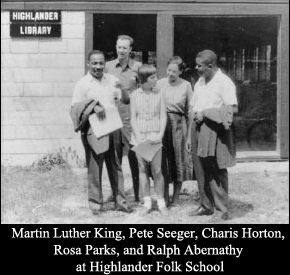

Hayes had learned sacred harp music in his minister father's church and worked at the embattled pro-union Commonwealth College in Mena, Ark. in the 1930s, and also with the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, an activist training school that connected Seeger to the civil rights movement.

In 1940, Hayes and Seeger joined with others to form the Almanac Singers, a name inspired by Hayes' observation that back in Arkansas "a family had two books. The Bible to help 'em to the next world. The Almanac, to help 'em through the present world." Closely tied to the activist unions of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the fluid Almanac lineup included Guthrie; Josh White, an African-American singer and activist from South Carolina; and Sis Cunningham, a white Commonwealth College graduate and former teacher at North Carolina's radical Southern Labor School for Women.

Going South

The Almanacs soon disbanded, but their popularity with progressives led Seeger to become the balladeer for Henry Wallace's New Deal-inspired Progressive Party bid for president in 1948. The campaign included a fateful week-long tour in the South, where Wallace's black and white team was met with violence at its first stop in North Carolina. Seeger later remembered that Wallace's advisors wanted to cancel the trip, but Wallace insisted they push deeper into the South. As a reporter for the Baltimore Afro-American wrote, "An integrated group, traveling through the South in 1948 ... We were sitting targets expecting to be blown up at any minute."

The hostility Seeger witnessed in the South was dispiriting, but it also sharpened his interest in the emerging Southern civil rights struggle, a focus he and Lee Hayes continued when they formed The Weavers in the fall of 1948. Before being commercially destroyed by Cold War hysteria, the Weavers had more success than the Almanacs, and many of their most popular songs had Southern roots: "On Top of Old Smoky," which Seeger picked up in Appalachia; "Pay Me My Money Down," a slave song from the Georgia Sea Islands; and "Darlin' Cory," a mountain song about lost love and moonshine.

The year 1948 was also momentous for another reason: That was when People's Songs Bulletin, a publication of the People's Songs group Seeger and Hayes led, published the words to "I'll Overcome Someday," a gospel song they credited to African-American composer Charles Albert Tindley. Seeger said he learned it from Zilphia Horton, who ran cultural programs at the Highlander school; she had heard it from striking tobacco workers in Charleston, S.C. in 1945.

As Seeger was always quick to admit, the origins of many of the songs he played, relayed by oral tradition, were murky, and "We Shall Overcome" is no exception. (A caustic 2012 book argues the source is another gospel singer, Louise Shropshire.) But there's no question Seeger was key to popularizing it -- playing it for Martin Luther King, Jr. at a Highlander reunion in 1957, and transmitting it to rising folk artists like Joan Baez, who went on to sing it at the 1963 March on Washington.

Other, less well-known Seeger songs chronicled different aspects of Southern political and racial history. "The Story of Old Monroe," which Seeger wrote with Malvina Reynolds in 1962, told the story of Robert F. Williams, the militant NAACP leader in Monroe, N.C. who advocated armed self-defense against the Ku Klux Klan. Echoing a similar theme, Seeger was the first to record another Reynolds song, "Battle of Maxton Field," hailing a successful effort by armed Lumbee Indians to drive the KKK out of Maxton, N.C. in 1958.

'One More Grain of Sand'

Seeger, of course, never stopped singing and speaking out, including delivering a spirited performance of "This Land Is Your Land" at President Barack Obama's inauguration in 2008, more than 50 years after McCarthyism and blacklists devastated his career.

Through it all, the South's rich musical and cultural traditions, as well as the harsh realities of racist violence and other injustices in the region, were a defining influence.

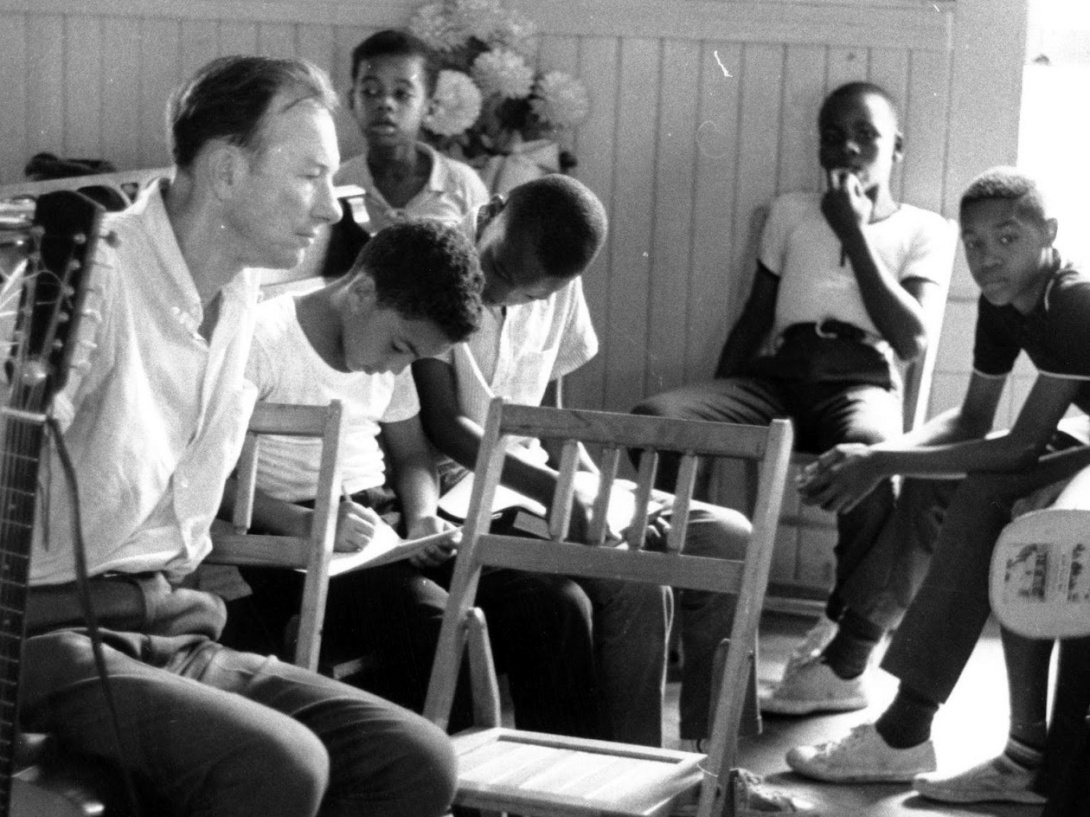

In his 1967 memoir "The Incompleat Folk Singer," Seeger includes a journal entry from 1964, when he came to Mississippi at the invitation of civil rights organizers to teach at movement-organized Freedom Schools. At one workshop, he remembers having to tell the audience that authorities had found the bodies of murdered activists James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner (a tragedy Seeger later sang about in the gentle but powerful ballad, "Those Three Are On My Mind").

It was a painful moment, one that would cause anyone to wonder what good they were doing, and whether change was truly possible. But Seeger always believed that it didn't matter how long the odds were -- the issue was which side you were on, and whether or not you'd cast your lot with ordinary people struggling for a better world. As he wrote from Mississippi:

And what am I accomplishing? some will ask. Well, I know I'm just one more grain of sand in this world, but I'd rather throw my weight, however small, on the side of what I think is right than selfishly look after my own fortunes and have to live with a bad conscience.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.