WV water contamination exposes chemical hazards of coal power

Most Americans are aware of the pollution hazards associated with the mining and burning of coal. The water contamination disaster that began unfolding last week in West Virginia is now drawing attention to another, often-overlooked hazard associated with coal power: the chemical-intensive process used to clean the fuel after it's mined and before it's burned.

Scroll below to listen or read along with this article.

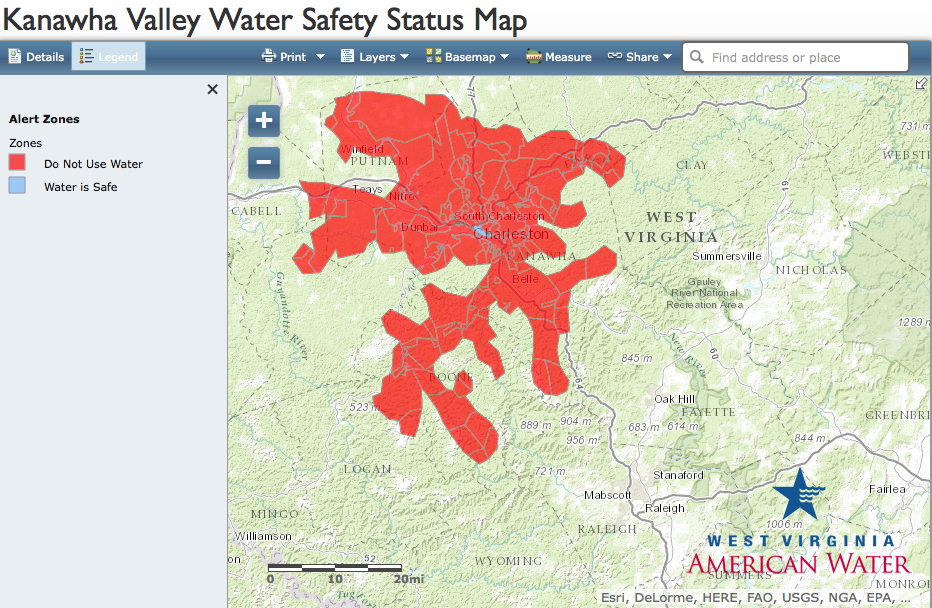

Last Thursday, reports of a strong licorice-like odor led to the discovery of a leak from a chemical storage tank at Freedom Industries in Charleston, W.Va. The leak released an estimated 7,500 gallons of 4-methylcyclohexane methanol into the Elk River, a tributary of the Kanawha. The site is about two miles upstream from the intake at West Virginia American Water's treatment plant that provides drinking water for some 300,000 residents of nine counties in the Charleston area, who were ordered to stop using tap water for anything besides flushing toilets.

The do-not-use order will be lifted in phases starting Monday, Jan. 13. Meanwhile, authorities were monitoring the chemical plume as it moved along the Ohio River into Kentucky.

4-methylcyclohexane methanol is manufactured by Eastman, and there isn't much publicly available information on its toxicity due to the weak U.S. chemical regulatory system. A West Virginia official told the Charleston Gazette that the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention looked for studies of the chemical's health effects and found only one -- a 1990 study by Eastman that wasn't published in a peer-reviewed journal and is considered proprietary. As the paper reported:

That study, she said, was the basis for the median lethal dose, or LD50, listed on an Eastman "material safety data sheet," or MSDS that's been circulated by local emergency responders, health officials and the media.

On that MSDS, the LD50 for Crude MCHM is listed as 825 milligrams per kilogram. This means that, when tested on rats, an 825 milligram dose per kilogram of body weight was enough to kill half the rats.

The Charleston Gazette points out that the LD50 measure considers only death and not other health effects related to exposure. Since the leak was reported, at least 14 people have been hospitalized for symptoms that could be related to the spill, according to the paper.

4-methylcyclohexane methanol is just one of the many chemicals used in the coal-washing process. When coal is mined, there are impurities in it that have to be removed before it's sold. In West Virginia and elsewhere in Appalachia, coal companies remove those impurities using a process called "wet washing." Here's how the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition's Sludge Safety Project describes it:

In a wet washing plant, or coal preparation plant, the raw coal is crushed and mixed with a large amount of water, magnetite, and organic chemicals. The chemicals are primarily patented surfactants, designed to separate clays from the coal, and flocculants, designed to make small particle clump together. In massive "flotation columns", most of the coal floats to the surface and most of the other material (called "coarse refuse") sinks to the bottom. The huge volume of waste water left over is coal slurry. In the slurry are particles of rock, clay and coal too small to float or sink as well as all the chemicals used to wash the coal. While the coal industry likes to claim that the particles of "natural rock strata" and chemicals are perfectly safe, testing has shown coal slurry to be highly toxic.

One of the chemicals used to process coal, polyacrylamide, was the subject of a lawsuit that led to a class-action settlement last year. The suit claimed that workers at plants using the flocculant were at a higher risk for nervous system problems and cancers of the testicles, adrenal gland, mammary gland, uterus, thyroid, pancreas, brain, spinal cord and lungs. The defendants -- chemical companies including Chemtall, CIBA Specialty Chemicals, Cytec Industries, and others -- did not admit wrongdoing but agreed to pay $13.95 million to settle the claims.

Freedom Industries serves as a distributor for other coal-preparation chemicals manufactured by Georgia-Pacific Chemicals. That's a subsidiary of Atlanta-based Georgia-Pacific, which in turn is owned by the Kansas-based Koch Industries oil and chemical conglomerate.

Workers at coal processing plants are not the only people at risk from the chemicals used there. The preparation plant waste that includes the chemicals as well as heavy metals and other impurities washed from the coal is most commonly stored in what are known as "coal sludge impoundments" -- massive dams that hold billions of gallons of the waste in valleys near the processing plants. As the Sludge Safety Project notes:

Most impoundments are not lined in any way. When an impoundment fills up with fine slurry particles and is abandoned, the remaining water is pumped off and the slurry is "capped" with a layer of coarse refuse.

There are over 110 of these impoundments in West Virginia alone. In 1972, a coal sludge impoundment in Buffalo Creek, W.Va. catastrophically failed, killing 125 people and leaving thousands homeless. That incident led to regulations for impoundments, but they have not halted failures altogether. In 2000, slurry from an impoundment in Martin County, Ky. broke through into underground mines below, spilling 300 million gallons of the waste, destroying the town of Inez, and polluting the Big Sandy River. Since then, there have been at least 16 coal slurry spills of over 1 million gallons and numerous smaller spills, according to the Sludge Safety Project.

And it's not only catastrophic failures of coal sludge impoundments that imperil communities, as the structures also leach contaminants into groundwater. In Clinton County, Ill., a coal sludge impoundment at a processing plant owned by an ExxonMobil subsidiary contaminated an aquifer, and local residents blamed cancers and other illnesses on the pollution.

Elsewhere, instead of being stored in impoundments, the sludge is pumped into underground mines, which also presents a groundwater pollution threat. In communities in West Virginia's Mingo and Boone counties, the injection of billions of gallons of coal slurry waste into abandoned mines ruined residents' well water, necessitating their connection to municipal water supplies. Boone County was one of those affected by the Freedom Industries spill.

Since the Freedom Industries spill came to light, West Virginia Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin (D) has emphasized that it was "a chemical company incident" and "not a coal company incident." But the disaster shows how dirty and dangerous coal is throughout its entire lifecycle, including its processing.

"Coal mining communities are faced with the dangers of water pollution from coal mining and pollution every day," says Mary Anne Hitt, director of the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign. "This spill pulls the curtain back on the coal industry's widespread and risky use of dangerous chemicals, and is an important reminder that coal-related pollution poses a serious danger to nearby communities."

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.